Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 7

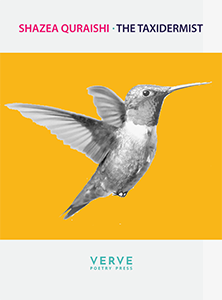

From The Taxidermist by Shazea Quraishi

Shazea Quraishi reads excerpts from The Taxidermist and discusses the sequence with Mark McGuinness.

This poem is from:

The Taxidermist by Shazea Quraishi

From The Taxidermist

by Shazea Quraishi

At the table she waits for the mouse to thaw

scalpel tweezers calipers

pins pipecleaners wire scissors

needle thread straw

Begins

taking apart

putting together

**

a white mouse, a feeder mouse

soft drift of white

his modest truth disarms me

forehead

ears feet

mouth

a dim rose

with teeth

I admire

this raw meat of us

this ease

**

a white mouse (2)

what has a white mouse to show us?

I meet him

white mute item

(fate

air hums with it)

he was

he is

I sew him shut

wish him home

**

Her hands intent precise thinking

miracle how living works stops

careful labour to preserve restore what? limbo?

past-in-present perhaps an imprint a 3-dimensional holding

of memory of once-being

She once heard someone say this is craft it lacks edge

(advantage power urgency force)

gets up to shift thoughts

Interview transcript

Mark: Shazea, where did this sequence of poems come from?

Shazea: That’s such a good question. And I often have to unpick the answer myself. So, with all my writing actually, well, particularly lately, I find that at some point, I’ll notice I’ve been drawn to something, a subject or something that has, like… it’s got a, sort of, magnetic pull on my attention. So, for several years, quite a few years, actually, I’d been thinking a lot about artistic process, and the artistic impulse. You know, also, I think as a poet, where, you know, famously, there’s not… I know, some people earn a good living, but there’s not famously. It’s not a very easy way to make a living. I was often…

Mark: Who are these people? [Laughter]

Shazea: I don’t want to name names, but some people do it very well.

Mark: Introduce me!

Shazea: Yeah. And kudos, kudos to them. But, you know, I don’t know if you have this mark. Sometimes, you know, when you wake up at 4 a.m., and sometimes I would be thinking, ‘Why am I doing this is? Is it self-indulgent?’ I’m not making enough to support my family, to be able to support… you know, to maybe see my mum in Canada a bit more. And so, I just became really interested in looking at other artists, and why they do what they do. So, that’s something that had been going on for many years anyway. And then I found myself drawn to taxidermy. I came across… there was a programme on the BBC quite a long time ago. I think it was called, What Do Artists Do All Day? And there was an interview with this…

Mark: Yeah, yeah. Great programme.

Shazea: Yeah, you remember that. There was an interview with this artist, Polly Morgan, who’s a taxidermy artist. Without knowing why, I just became… it just really, really grabbed my attention. And then I started doing more research. And I discovered that there’s been a kind of movement over the last decade or more, for young female taxidermy artists, and how their approach is quite different to the, sort of, traditional male-dominated… Well, there’s the, you know, taxidermy, which is sort of scientific and museum-based. And then there’s also the kind of hunting, fishing, trophy, sort of, taxidermy.

And this was a very different approach to it. There seems to be a kind of… perhaps that’s just how I saw it, a kind of tenderness, and a respect, and a kind of holding up, and exalting of these small, brief lives, which I was really moved by. And then I think at some point… I don’t know when I sort of… And I’ve always been a little… I’ve been thinking about death for a very long time, well, as I suppose we all do. But my father died quite suddenly when I was 20, and that kind of really changed me, and changed my world. And I suppose I’ve been, sort of, thinking, and, sort of, trying to kind of make sense of how we live with our dead beloveds, I suppose.

And then I don’t know if it’s before or after this taxidermy thing, but my younger brother, Asad was diagnosed with a terminal illness, and then he died. I think it was just over two years ago. And so that, I think, was… that kind of grief was probably… I think it’s very much in this book, but I knew I didn’t want to write about grief because I find when I’m in grief, it’s completely stultifying. And also, I mean, I think I did try to write about grief in it, and it was just… didn’t offer anything to me or to a reader.

And so I think I just really was looking for how to kind of bring in the kind of joy of being alive, and how to partner that with this kind of loss as well. And so I think that, for me the taxidermist just came… you know, it sort of offered itself as a way for me to write about something that was very personal, but to write about it in a way that I could offer something, well, that I’d like from it as well as something that I could hopefully offer to the reader.

Mark: Well, you’ve certainly done that. I mean, it’s a short book. Well, obviously, it’s a pamphlet, so it’s short by design, but there’s an awful lot in it. And I sense that… I mean, I didn’t know the background until I asked you just now. But there’s a lot of close-up in the poem, a lot of looking at creatures in really minute detail as a taxidermist obviously would.

So, there’s a lot of close-up foreground going on, but you get a real sense of a hinterland, a background. And clearly, that’s there for you as the writer, but maybe it’s also there for the taxidermist in the poem, because we see a lot of her close-ups of what she is focused on in the moment, in the foreground. But I also get a sense that there’s a lot going on in her life just out of shot, so to speak.

Shazea: Yeah, I really love that you see it in that way. I won’t talk about form at the moment, but I… A lot of things sort of fortuitously fed into this. I was lucky enough to get a place on a writer’s residency in Mexico in Oaxaca. And so that was early last year, kind of from mid-January until March, so just before the pandemic. And I really saw that as being the setting for this book, and for the wider collection that I’d been working on for a while. So, The Taxidermist pamphlet is… I think of it as an aria. It’s very much just a very internal experience of the taxidermist, and it’s very, sort of, closed. And I just really wanted it to be as if we are experiencing what she’s experiencing, and thinking what she’s thinking, you know? And I wrote the bulk of it in the first lockdown because the…

Mark: Oh, really?

Shazea: Yeah, well, because my manuscript was due, I think, in June or something like that. And so, I was literally in my little writing shed in the garden. We have a very small garden which just fits the writing shed, and a little bit more. And, of course, it was lockdown, so my daughter was home, and my son was home, and we were all in the house. So, I would go and write in the shed. And it’s very small. It’s like 4 by 6 feet. And so I was very much feeling… I feel like that probably really informed, as well, the feeling. Although it’s set in Mexico in this place that I went to just outside Oaxaca, but she’s just inside pretty well the whole time of the book.

Mark: Yeah. And maybe also to help the listener who hasn’t read the whole sequence yet, one of the things I notice is the shift from the third person to the first person. And we get some views of the taxidermist’s life, and her interaction with the townsfolk in this place where she goes to in Mexico. But then you shift into the first person, which is like a moment where we… you know, the camera angle shifts to focus on her view of this, the desk, and the poor, little, white mouse that she’s working on. And we can hear that in this excerpt that you’ve just read. You know, you start off with the third person, and then you go into the first person. And, you know, it really does give that sense that we’re in very close proximity with the taxidermist, and obviously, with the mouse.

Shazea: Oh, that’s great. You know, I hadn’t actually noticed that. I suppose it was just… I mean, so much of my writing is through discovery, and inquiry into something. And often, I don’t know what I’m going to say or what I’m doing until I can look back on it. You know, it’s very much about just being in it. But now that you say it, I can see that it is very much… there is that kind of wide angle looking at her, and then it’s her… And actually, I don’t know if you can tell from my taxidermy prints, but I did taxidermy a white mouse…

Mark: Wow.

Shazea: …just because I thought I have to know… and actually, the white mouse, and it cost £43. Whereas I’d love to have done a bird, but it’s a lot more expensive, and I don’t think, actually, I was up to that. So, yeah. I mean, accuracy is so important to me as well, accuracy, obviously, of language, and accuracy of emotion, and thought. But also very much I wanted to make sure that, you know, the taxidermy poems are emulating the act of taxidermy as well as reflecting on it.

And so, I wanted to know what it was like. And I have to say I thought it would be this lovely… you know, there’s just this lovely paying homage to this lovely animal, and it is meat and kind of gristle. And when I was doing it, accidentally, I pulled the foot off, but you know, she didn’t… the teacher said, ‘Oh, don’t worry, we can reattach that really easily.’

Mark: So, this is method poetry. You’re the Daniel Day-Lewis of contemporary poetry! Gosh, I didn’t realize you’d gone that far. But, absolutely, the accuracy… I mean, the two words I wrote down when I was thinking about this conversation were delicacy, and precision. I mean, I love the way you start off. ‘At the table, she waits for the mouse to thaw, scalpel, tweezers, calipers, pins, pipe cleaner, wires, scissors.’

When you lay those words out on the page, it’s like that’s how she’s laying the tools out on the desk. And I also got a strong sense of that crossover between the artist and the taxidermist. Well, I mean, I didn’t get it first time round, but after a few readings, the penny started to drop. But I had no idea that you had gone the whole hog, so to speak, to make this as accurate as possible.

Shazea: I also watched… because I have one about these really big snakes, Olmecan pit vipers, so I watched… There’s loads on YouTube, usually from the States, watched kind of taxidermying snakes. And there was something I watched. I can’t remember what it was, but it was… I found that, like, really quite grisly. But, yeah, I did try to be as accurate as I can, you know. And meat, you know, I wouldn’t have known… If I hadn’t done it, I wouldn’t have known just how, obviously flesh, you know, it is. And removing the skin from something is a really kind of big thing, actually.

Mark: And maybe, you know, for the benefit of the listener who may be, like me, feeling a little queasy at this point, your taxidermist does say somewhere in the poem that she only works with animals that have died of natural causes. She’s not a small game hunter, is she?

Shazea: No. That’s something also I found from watching kind of interviews and videos with these female taxidermists. So, it’s called ethical taxidermy. And a lot of times, once a taxidermist is well known, or a taxidermy artist, some people like Polly Morgan is very much more towards the art. And actually, also, another taxidermist, Divya Anantharaman, if you’re interested in taxidermy art, she kind of is part of Gotham… I think it’s called Gotham Taxidermy, is her Instagram feed, which is just really so interesting.

But yeah, so ethical taxidermy, it’s only animals who have died in natural, or unpreventable deaths. So, for example, the mouse I used is a feeder mouse. They’re bred as food for snakes, and lizards, and reptiles. And you buy them frozen from pet stores. And so, you do… when I came to the taxidermy class, she said, ‘Well, hopefully, your mouse will be thawed by now.’ So, you know, I think I wouldn’t have known that if I hadn’t actually done it myself.

Mark: Well, I’ll make sure we link in the show notes on the website to those Instagram feeds and taxidermy artists…

Shazea: Oh, brilliant.

Mark: … just so that people can check it out for themselves if they’re feeling brave. And there is, you know, picking up on what you said earlier on about not being in the masculine tradition of taxidermy, you know, the hunting, and museums, and conquests, and, ‘Look what we brought back from Borneo,’ kind of thing in Victorian museums. I really got an unexpected sense of care and love, you know, in that third part where the taxidermist says, ‘I sew him shut, wish him home,’ is so sweet, and at the same time, it’s also quite macabre. You know, but I do get a sense that there is a lot of genuine love, and compassion going into this art, even though it’s not gonna do the mouse much good.

Shazea: Yeah, I’m glad you see that. You know, sometimes the animals have had such brief lives. Like butterflies only live a couple of weeks, you know, depending on their size. I just find that gives me such… it’s a really useful perspective to have in terms of our lives, and our place on the earth. So, yeah, I do feel a great tenderness, and I look at… you know, I try and research the animals that I taxidermy. I mean, I look them up. I say… think how big is it? Would it have lived in Mexico? And then I watch videos of what they look like alive just to know how they behave. And I do feel a great tenderness towards them as I think the taxidermist does as well. And, you know, the women that I’ve been interested in, and who I’ve learned a lot from, they’re all the same as well. I think there is a real… That’s kind of very important, actually.

Mark: And when you talk in the poem about preserving these very brief, fleeting lives, it reminded me of Philip Larkin, when he said once that he didn’t write poetry to communicate, but he wrote it to preserve an experience.

Shazea: Yeah, I really agree with that. I didn’t know that Larkin quote. Absolutely. I’ve had for a very long time, a bad memory. So, I do find it… I don’t know if I started writing to preserve thoughts and feelings. But also, I found that writing for me is so much about discovery. And for me, it’s very much about making sense of things, and of my place in the world, and, you know, our place, I suppose, in the world, but in a way that is not just about me. But hopefully, I would want to be kind of generous to the reader so that there’s also a place for the reader to… you know, leaving space between the words, and in meaning, for the reader to bring their own meaning at some point, as well. So, I don’t want to lay it all out immediately. So, there are lots of gaps and spaces, which I hope the reader will… as you said, you know, will bring their own experience and their thinking to what they make of the work.

Mark: Absolutely. And I’m looking at the text here laid out. And this is something I’ve admired about your work for years, Shazea. The way you can lay words out on a page, and the whitespace, and the gaps, and so on, you know, it’s something you can’t teach. You’ve either got it, or you haven’t. So, I’d really encourage listeners to check out the text. It’s on the website, and it’s also, obviously, printed in the pamphlet, The Taxidermist. How do you see the relationship…? Because on one level, I think of you as a very visual poet, the way you lay the text out on the page, but also, as we’ve heard, it can also be beautifully read. So, how do you see that relationship between the two versions of the poem?

Shazea: That’s such an interesting question. Well, for the page, particularly… Well, I think for both, but particularly, the more narrative poems, which I really wanted to recreate the experience of her thinking, even though it’s from a more wide angle, and it’s not from the I point of view. But I wanted it to be kind of thinking as she’s thinking, and then she corrects herself, so with the kind of striking out of words. You know, when we’re thinking, we think, ‘Is it this? No, no, it’s more like this.’ And so I wanted to include all those kind of corrections and approaching of thoughts on the page.

And so I really wanted to score it in… you know, using whitespace because I didn’t wanna use punctuation because it’s her… although it’s in the third person, it’s kind of very much an internal kind of thought process, a lot of the times. Instead of punctuation, I wanted to score it so that the reader still has a sense so that it helps the reader in how to read the poem both in terms of pace, but also in terms of meaning, so really using kind of line breaks to deflect or emphasize things to have more than one meaning for things. So, you’re just using as much because it is quite narrative, but I wanted to bring all the tools of poetry that I could bring into it like… you know, like sound and metaphor, and kind of having multiple meanings, and things like that.

Mark: Yeah. And I love that word, score, that you use. It’s like you’ve written, like, a score for a piece of music. And I feel like if I’m looking at this, and I’m reading it out loud, myself, you’ve indicated to me how to do it, where to put the pauses, and the hesitations, and the emphases and so on. And this is something I really encourage you to do, dear listener, is to get the text, and read it out loud for yourself. Because I’ve said several times on the show, it’s a very different experience when you’re reading it, and you’re feeling it in your own mouth, your own body, instead of just being on the outside looking in at the text. So, try out Shazea’s score, because she’s laid it out for you in such a way that it’s not hard to know how to pace the reading.

Okay, focusing a little more on the specific form that you’ve used in the sequence, I had to do a double take when I got to the end of the pamphlet because you have this very intriguing little footnote where you talk about the specific form you used in the first-person taxidermy poems. So maybe you could say something about that because it made me look at the whole sequence in a completely different way.

Shazea: Oh, that’s so great. And I loved that it was… I mean, I just really like putting it as a note at the end so that people could then go back and look. So, the taxidermy poems are in an anagram form, which is a form that’s used by Oulipo, which is a post-surrealist French group of writers, mathematicians, and scientists. So it was founded in 1960, I think this group, and their members have included novelists like George Perec and Italo Calvino. So, their whole thinking is that potential literature is kind of new structures and patterns that come out of using constraints. So, for them, it’s all about constraints and how constraints are used as a means of triggering ideas and inspiration. So, I think it was Perec who wrote a whole novel in French, I think it was him, without the letter E. I mean, if you know, French, you know, that would be… you would think that’s impossible.

Mark: Yeah, not easy, certainly.

Shazea: Not easy. No. So with the anagram form, I used… So the title, which is the animal, so, instead of saying… If I just said, ‘white mouse’, for example, I would not have had an A, which would limit what I could write. Actually, the first one I did was a white mouse, a feeder mouse. And I started off doing these anagram poems just figuring out the anagrams on my own. And I’m not very good at puzzles, so I would just brainstorm all the words I could come up with.

And then I was teaching, it’s interesting, the poetry school. I had written a few of these mouse poems, and I think I’d even published some in the Hudson Review, this really amazing American journal. And then I took it to my class to my students, and they were coming away with, like, these incredible poems with all these words. You know, and I think there was one student, Sean and I said, ‘Okay, your poem is really good, but also, my God, you’ve come up with all these words.’ And all the students looked at me. They said, ‘Yeah, we used an online word generator. You don’t have to do it yourself. It’s, like, you feed it in.’

So, after that, I started using the online word generator, which is kind of a double-edged sword because you end up with… So, for example, I’m just working on a taxidermy poem now for… I just did a nine-banded armadillo. And I think there were almost 2,000 possible words that you then have to… It’s really interesting because it sort of turns the editing process on the head. So, you do all the editing, or the way I do it anyway, with the online… is I go through, and I pick out all the kind of possible words that I might use in my poem. And then I write a long list of them. So, I might end up with 400, or 300. And then from then… that’s kind of my palette, which becomes my word palette, but also my sound palette with the anagram form. I don’t know if you noticed, but because the letters are so limited, there’s a real kind of soundscape, as well, to the poems.

Mark: Well, I kind of had the sense that there was something going on. You know, it was quite an odd effect. It was maybe similar to the experience of reading, you know, Marianne Moore’s syllabics. You get the sense even if you don’t know, and you haven’t counted, that there’s something going on here. And I can’t quite put my finger on what it is, but it’s having a really interesting, slightly odd, effect, which I really liked about it. So, it was really delightful to then get the key to the mystery in the note at the end of the book.

And I really think this is a great example of what people often say about form, is that the constraints push you to consider possibilities you wouldn’t have considered otherwise, that you end up with. I mean, you know the cliché about form, is it’s supposed to be a restriction. But really, what you’re showing here is that it opens up new possibilities. And it becomes more surprising than what you might have got without the constraints.

Shazea: Yes, absolutely. I mean, just having these specific words to work from, I found it so freeing. You know, sometimes I do get a headache after looking… sifting through 2,208 words to find words that I wanna use. And then you kind of sift through more and more. So that is quite intense, but then you end up with words that… you know, that I wouldn’t have come to myself. So it does really surprise. It surprises me, and I feel like it takes… just opens the poem up to all these possibilities, which is what I love, you know, surprise for me as a writer, and surprise for the reader. For me, this is kind of the thing I love most in poetry.

Mark: Well, it was certainly a surprising experience to read and then reread the sequence, and also to hear some of it today. So, thank you, Shazea. And I think this is a really nice point at which to hear the poems again.

From The Taxidermist

by Shazea Quraishi

At the table she waits for the mouse to thaw

scalpel tweezers calipers

pins pipecleaners wire scissors

needle thread straw

Begins

taking apart

putting together

**

a white mouse, a feeder mouse

soft drift of white

his modest truth disarms me

forehead

ears feet

mouth

a dim rose

with teeth

I admire

this raw meat of us

this ease

**

a white mouse (2)

what has a white mouse to show us?

I meet him

white mute item

(fate

air hums with it)

he was

he is

I sew him shut

wish him home

**

Her hands intent precise thinking

miracle how living works stops

careful labour to preserve restore what? limbo?

past-in-present perhaps an imprint a 3-dimensional holding

of memory of once-being

She once heard someone say this is craft it lacks edge

(advantage power urgency force)

gets up to shift thoughts

The Taxidermist

The Taxidermist by Shazea Quraishi is published by Verve Poetry Press.

The Taxidermist is available from:

The Publisher: Verve Poetry Press

Bookshop.org: UK

Shazea Quraishi

Shazea Quraishi is a Pakistani-born Canadian poet and translator based in London. She teaches with the Poetry School and is an artist in residence with Living Words.

Shazea’s poems have appeared in UK and US anthologies and publications including The Guardian, The Financial Times, Modern Poetry in Translation, Poetry Review, The Hudson Review and New England Review.

Her books include The Art of Scratching (Bloodaxe Books, 2015), The Courtesan’s Reply (flipped eye publishing, 2012), which she is adapting for stage, and most recently The Taxidermist, a chapbook (Verve Poetry Press, 2020). Her next collection is forthcoming from Bloodaxe Books in 2021.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Pregnant Teenager and Her Mama by Carrie Etter

Episode 68 Pregnant Teenager and Her Mama by Carrie Etter Carrie Etter reads ‘Pregnant Teenager and Her Mama’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: Grief’s AlphabetAvailable from: Grief’s Alphabet is available from: The publisher: Seren...

To His Coy Mistress by Andrew Marvell

Episode 67 To His Coy Mistress by Andrew MarvellMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘To His Coy Mistress’ by Andrew Marvell.Poet Andrew MarvellReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessTo His Coy Mistress By Andrew Marvell Had we but world enough and time,This coyness,...

Homunculus by the Shore by Luke Palmer

Episode 66 Homunculus by the Shore by Luke Palmer Luke Palmer reads ‘Homunculus by the Shore’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: HomunculusAvailable from: Homunculus is available from: The publisher: Broken Sleep Books Amazon: UK | US...

0 Comments