Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 38

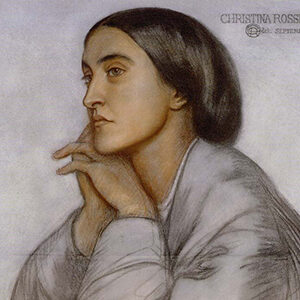

In an Artist’s Studio by

Christina Rossetti

Mark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘In an Artist’s Studio’ by Christina Rossetti.

Poet

Christina Rossetti

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

In an Artist’s Studio

by Christina Rossetti

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more or less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Podcast transcript

This sonnet by Christina Rossetti is delightful and disturbing in equal measure.

As the title announces, we are in an artist’s studio. Rossetti wrote this poem in 1856, the heart of the Victorian age, and given that she doesn’t suggest any other era, I think we are justified in seeing this as a contemporary Victorian scene.

And in the studio, a male artist is looking at a female model and making of her what he will, as artists generally do with their models. He’s getting her to pose as a queen, a ‘nameless girl’, a saint and an angel, so he can paint her.

So far, so conventional.

But by the end of the poem, it’s turned from vivid description into a pointed critique of the male treatment of women in art. Not only that, but this poem is by a female poet – which means we’ve got a female artist looking at a male artist looking at a female model.

If it were written by a man, it would still be a really good poem, but there would be several levels of irony and meaning missing. And you know me, I’m generally a little circumspect about bringing too many biographical details to bear on our interpretation of a poem, but this is one case where I really think it’s pivotal to the meaning, for us to be aware that Christina Rossetti is a woman. Because this is a poem that comments on power relations between men and women, as manifest in artistic representation, so it really matters that the poem is by a female poet.

In later parlance, she deconstructs his gaze. In more conventional poetic terms, she’s holding up the mirror to the ‘mirror’ of his art. And of course, when you put mirrors facing each other, you can expect all kinds of distorting and disorienting effects, and this poem certainly does not disappoint on that score.

So the situation is dramatic, and there’s a dramatic tension not just between the artist and model in the poem, but between the poet and her subjects. And for me, what elevates this poem from ‘really good’ to ‘absolutely brilliant’ is the fact that Rossetti deliberately and artfully uses not only the content but also the form of the poem to dramatic and subversive effect.

So as I said, this is a sonnet, and we’ve seen several types of sonnet already on this podcast – Mimi Khalvati read us a Petrarchan sonnet in Episode 3, and spoke very eloquently about the differences between the Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnet; in Episode 4 I read Shakespeare’s Sonnet 60; in Episode 11 Jaqueline Saphra read us her very contemporary and topical ‘Lockdown Sonnet LIX’; and last month, in Episode 36, we saw how Tennyson played rather fast and loose with sonnet form, using 15 lines instead of the usual 14, and essentially only two rhymes, as well as repeating some of the same words instead of rhyming different words. But as we saw, critics have still given him benefit of the doubt and categorised his poem ‘The Kraken’, as a sonnet.

But here, Rossetti leaves absolutely no room for doubt that this is a sonnet, and a very particular kind of sonnet at that – the Petrarchan sonnet, also known as the Italian sonnet. The original and some would say the best kind of sonnet, which is named after Francesco Petrarca or Petrarch, as we generally Anglicise his name, who was a poet writing in 14th century Italy.

And the essential thing about the structure of the Petrarchan sonnet, as Mimi Khalvati pointed out, is the division between the first eight lines, known as the octave, and the final six lines, called the sestet. And the octave is basically the setup, or in this case, setting the scene, while the sestet follows on with a shift of perspective or a new line of argument, offering some kind of contrast with the octave. And the point where the octave shifts into the sestet, in the ninth line, is called the turn.

‘In an Artist’s Studio’ adheres precisely to this structure, with the first eight lines describing the scene in the studio, as a visitor is shown the various canvases and can’t help noticing the same face, ‘the selfsame figure’ in ‘all his canvases’:

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more or less.

So let’s take a moment to appreciate the vividness and grace of the writing here. Rossetti is using a very regular iambic pentameter, with all but one line end-stopped, meaning the end of the line coincides with the end of a phrase or sentence. And if you’ve ever tried writing like this, you’ll know it’s difficult to do it without sounding stilted and robotic, or without resorting to archaic vocabulary and syntax, to get the words to fit the form.

It’s a virtuoso performance on the part of the poet, that subtly mirrors the virtuoso performance by the model. And it’s only at the very end of the octave that we get a slight shift in form and tone, a bit like a model starting to wobble after holding the same pose for too long. So first of all, we have the first enjambment, when the sense of the phrase runs over the end of the line:

every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more or less.

So the word ‘means’ is the end of the seventh line, with the phrase running over and adding ‘meaning’ to ‘means’ – she’s really signalling this word is important, through the repetition, the positioning at the end of the line and the enjambment. So what does she (ahem) ‘mean’ by it?

Well she’s saying very clearly and plainly that the artist’s work is one-dimensional, it just has ‘The same one meaning, neither more nor less’. And if you recall Matthew Caley last month, who said that there is no ‘equals’ sign for a real poem, you can’t say ‘this equals that’ and ‘translate’ a poem into a single meaning with a prose summary… Well if you remember Matthew saying that, then you’ll know that Rossetti is delivering the kiss of death to the artist’s work, saying it’s not real art.

And then we get this brilliantly dramatic moment, in the turn, the ninth line that opens the sestet:

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

I don’t know about you, but when I first read this line, I did a double take. Did she really just say that? After all the sweetness and light of the octave, the ‘loveliness’ and the ‘freshest summer-greens’, we have this horrific image, as if the artist has been standing back and politely admiring and directing and painting her, and then he’s suddenly lost control and attacked her.

And it’s made more dramatic by the fact that this is the artist’s first appearance in the poem. The first line mentions ‘his canvases’, but after that all the attention is on her and the paintings, the artist himself isn’t mentioned.

And of course when we do a double take, we realise with relief, that it’s just a metaphor, he’s not really feeding on her face, but hungrily absorbing her beauty and using it for his art. But even that is pretty unsettling. And we can’t unsee that horrible image, however we try to rationalise it away.

It’s like that jumpscare in the Lord of the Rings movie, when Bilbo is talking to Frodo and he’s overcome by his desire for the Ring, and his face changes into an evil mask as he lunges at his beloved nephew to grab the Ring off him. He recovers himself straight afterwards and he and Frodo try to brush it off and move on, but none of us can unsee the image of horrible Bilbo. Just as, back in the artist’s studio, we can’t help seeing this vampire lurking beneath the loveliness.

So Rossetti uses the structure of the Petrarchan sonnet to superb dramatic effect. She also sticks very strictly to the traditional rhyme scheme associated with this sonnet form, which is notoriously difficult to manage in English.

So the original rhyme scheme, with letters standing for the rhymes at the ends of lines, goes ABBA ABBA in the octave, which means you only have two rhymes and each one is repeated four times. And this is a lot easier to do in the Italian used by Petrarch, because the structure of the Italian language means there are a lot more rhyming sounds than in English.

So finding four rhymes in English and sounding natural at the same time, is really hard to do, and a lot of poets fudge it by using an easier variation of the rhyme scheme. But Rossetti doesn’t fudge it at all, she sticks strictly to ABBA ABBA. And not only that, she uses monosyllabic full rhymes, which makes it even harder.

So poets often try to disguise or vary their rhymes, by using half rhyme, or varying the number of syllables in the rhyming words. So for example, you might rhyme ‘leans’ with ‘thins’, so you’re rhyming the consonants by varying the vowels. Or you could rhyme ‘leans’ with ‘machines’, a two-syllable word, which softens the effect of the rhyme.

But Rossetti doesn’t take the easy way out: she rhymes ‘leans’ with ‘screens’, ‘greens’, and ‘means’ – which puts even more emphasis on that key word, ‘means’. And there are just two exceptions to this pattern, of full monosyllabic rhymes, in the whole poem. One of them is the rhyme between two three-syllable words, ‘canvases’, and ‘loveliness’, in the first and fourth lines. But even here there’s a perfect symmetry between those two words, so they feel beautifully judged and balanced.

Not satisfied with a perfectly rhymed octave, Rossetti also uses the most demanding rhyme scheme for the sestet: CD CD CD. Even within Italian poetry, there are easier variations, which means you only need double rhymes, but this version demands two sets of triple rhyme, three C’s and three D’s. And if you’ve never tried it, this might not sound like a big difference, but I can assure you that triple rhymes are a lot harder than double ones. And once again, Rossetti limits herself to single syllable words: ‘night’, ‘light’, ‘bright’, and ‘him’, ‘dim’, ‘dream’.

And if we look beyond the rhyme words, there are only two words in the whole sonnet with three syllables, and only 18 words with two syllables. The other 96 words have only one syllable.

So what Rossetti has given us is what we could call a stripped down sonnet, reduced to the bare bones, with a very regular metre, structure and rhyme scheme and using very simple words. She also uses very few adjectives, all of them simple and in themselves pretty unremarkable, even bordering on cliche, such as ‘A nameless girl’, or ‘true kind eyes’. I can’t stress enough how difficult it is to do all this, without sounding banal or robotic.

There’s nowhere to hide when you write as plainly as this – with no unusual words or images or adjectives to distract the reader, the clarity of your thinking is laid bare in the structure of your syntax. So you need to have something to say, and say it well.

Okay, so this is a highly-skilled, high-wire performance by Rossetti – she’s showing ‘I can do this as well as anyone’ – certainly as well, I think the implication is, as any man.

And if you listened to last month’s episode, you will probably have noticed that this is the exact opposite of what Tennyson did with the sonnet form. Compared to ‘In an Artist’s Studio’, ‘The Kraken’ is positively sloppy and dishevelled and louche, with its 15 lines and its turn that doesn’t bother to get out of bed until the tenth line, and its extravagant adjectives and it’s polysyllabic Latinate diction, ‘unnumbered and enormous polypi’ and so on.

And as I said, the critics have generally given Tennyson the benefit of the doubt, and said, ‘Yes it’s a bit wonky but it’s still basically a sonnet’. But supposing the roles were reversed, and Tennyson had written ‘In an Artist’s Studio’ and Rossetti had written ‘The Kraken’? Would she have been given the same leeway? I think we have leave to doubt it.

But anyway. Rossetti’s brilliance doesn’t stop here. Because she could have made a virtuoso success of any poetic form, or if she’d wanted a sonnet, she could have done the Shakespearean version, which is generally considered to be easier to write in English.

So why did she pick the Petrarchan sonnet?

Because this is a poetic form with very strong associations with a particular genre of poetry, and a very particular set of conventions about the nature of romantic love and the roles of men and women.

The sonnet form did not originate with Petrarch, a scholar in 14th century Italy who fell in love with Laura, a woman he loved and admired from a distance, because she refused him on the grounds that she was already married to someone else. But his loss was literature’s gain, because he poured out his love in a series of sonnets that were extremely popular and influential on the development of European lyric poetry. Just as the three minute pop song was never the same after The Beatles, so the sonnet was never the same after Petrarch.

Petrarch’s sonnets were very much aligned with the medieval conventions of courtly love, in which a male lover admires and praises a woman who is typically distant, chaste, unattainable and elevated to an ideal that is practically sacred. And within the structures of medieval society, there’s something to be said for the way courtly love gave women such a high status, albeit in a very restricted context.

But as the centuries went by, and more and more poets poured out poems about saintly, chaste and unattainable ladies, it became more and more noticeable that this was a poetic tradition in which male poets projected their romantic dreams and fantasies onto a women – just as the painter in Rossetti’s poem projects his dream onto the model. The woman is treated like blank canvas for the man to paint on, her feelings aren’t really part of the picture. Or part of the sonnet.

And so what Rossetti has given us, quite deliciously, is not just a woman looking at a man looking at a woman, and deconstructing his fantasies and showing the dark side of the traditional gender roles and power dynamic – but she’s doing all this in a poetic form that is strongly associated with this traditional power dynamic.

She’s using the Petrarchan sonnet as a critique of Petrarchan attitudes to women, which were very much alive and well in the nineteenth century – for example, in the Pre-Raphaelite painters, who, rather interestingly, included Christina Rossetti’s brother, the painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti. I’d love to have been a fly on the wall when he read this poem for the first time!

We saw a similar use of form in Sir Thomas Wyatt’s poem, ‘They Flee from Me’, back in Episode 14, where he uses Geoffrey Chaucer’s rime royal stanza, which to me is a clear signal that he wants us to associate his own heartbreak with the tragic love story of Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde.

But whereas Wyatt uses form to elevate his own poetry and bolster it by association with medieval courtly love, Rossetti uses form to undercut and critique the same tradition. It’s the perfect way to undermine the idea that men are natural artists and women are natural models – to take the form associated with the male artist and write it brilliantly, almost perfectly. It just wouldn’t be the same with a different form.

So this is one more reason why we always need to be alert to form when we read a poem, to catch this kind of reference or critique or sometimes a really good joke. And Rossetti’s sonnet should be a challenge to the way poetic form is currently perceived in many areas of the 21st century poetry world – the idea that traditional forms are inherently old-fashioned and conservative, even patriarchal. And I think this is a really lazy assumption, because what Rossetti does brilliantly here is show us that the meaning of a poetic form changes with context.

So when a 14th century man wrote sonnets about a woman, the form had a different context and therefore a different meaning to when a 16th century man wrote sonnets about another man. In Shakespeare’s case, the scholars are still arguing about the exact nature of the man-to-man relationship, or relationships, he wrote about in such an overtly romantic form.

And so there’s a different context and a different meaning again when a 19th century woman writes a sonnet about a man painting a woman. And it follows that for persons of any gender writing about each other in the 21st century, the sonnet form can and will have all kinds of different meanings and resonances.

To misquote Hamlet, ‘there’s no form either good or bad, but thinking makes it so’. The only limits to formal expressiveness are the imagination of the poet and the sensitivity of the reader.

And form is just one aspect of the hall of mirrors Rossetti has created in this poem.

So to recap, she begins with a lively description of the model as she is directed and portrayed by the artist. And from one perspective, maybe there’s nothing much wrong with this. He is an artist and she’s a model, and posing for pictures is what models are generally supposed to do, and are often paid to do it.

From another perspective, it’s hard to argue that the depiction of the activity in the studio and the resulting paintings is wholly negative. Is there not an unmistakable zest in the description of the model playing all these roles, and a genuine appreciation of ‘all her loveliness’?

From another perspective, Rossetti is clearly saying that the art may be superficially brilliant but it’s flat and one dimensional. As she says in the sestet, it’s just his ‘dream’ of her. The woman ‘as she is’ never appears in his paintings:

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

So there’s a loss to art here. But also, I think there’s another level of poignancy, because the reason that the woman as she is never appears in his paintings is that he never looks at her, he never sees her ‘as she is’. So it’s his loss on a personal level. And by implication, not just the artist but many if not most men in this society are not seeing the women in front of them.

And I have to be careful here, and remember that I’m a man talking about a woman writing about a man painting a woman. So I bring my own blind spots and cultural assumptions to the poem. I’m certainly not saying the artist is ‘the real victim here’, but just that when there’s an unequal balance of power, this has a negative effect on everyone involved.

From yet another perspective, Rossetti’s poem, as I’ve said, is a brilliant performance, but it could be critiqued for staying too neatly within the parameters of a poetic form defined by male poets. It could conceivably be said to be too close to the model’s performance. But as I said earlier, Rossetti writes the Petrarchan sonnet almost perfectly. There’s one crucial flaw in the poem, one clue that she leaves, I think, quite deliberately and obviously at the end of the poem:

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Did you hear that? That’s right, the final word, ‘dream’, is not a perfect rhyme with ‘him’, and ‘dim’. It chimes on the consonant, but not on the vowel.

So firstly, I think we should pause to savour the fact that she’s rhymed ‘him’ with ‘dim’, which even in the 19th century would have had associations of ‘stupid’ as well as ‘faintly lit’. Now that may or may not be a sly joke on Rossetti’s part, but certainly as far as the final rhyme goes, given her perfectionism throughout the rest of the poem, it’s impossible to believe this is not a deliberate imperfection.

She could easily have used a full rhyme, maybe ‘whim’, and written something like:

Not freely but according to his whim.

But she doesn’t give us the expected full rhyme. The half rhyme is like a hairline crack in a china vase; a reminder of the fragility of the perfect object. Or in this case, a hint that all is not as it seems in these beautiful canvases; that they conceal not only the vampiric artist ‘feeding on her face by day and night’, but also a real person, who is ‘wan with waiting’ and ‘dim’ with ‘sorrow’, who had a story to tell, and maybe pictures of her own to paint, that never saw the light of day.

And one final perspective: who is Rossetti referring to when she says ‘We found her hidden just behind the those screens’? She doesn’t spell this out, but it suggests that the speaker of the poem has visited the studio before, and that she and others saw the model herself emerging from behind ‘those screens’ and reflected in ‘That mirror’. Which, within the world of the poem, might be a clue as to why the speaker is so keen to tell us what is missing from the artist’s portrayal of her.

And to me, this ‘we’ also suggests you and me, and anyone else who reads or listens to the poem. It sounds like a witnessing ‘we’ – suggestive of a world outside the artist’s studio. A world where people can reconsider the relationships and structures that are playing out in microcosm within the four walls of the studio, or the four sides of the sonnet.

And I could keep going, with more and more perspectives, and I have no doubt you could point things out to me that I haven’t spotted. Because Rossetti’s art, unlike that of the artist in the studio, is anything but one-dimensional.

In an Artist’s Studio

by Christina Rossetti

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more or less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Christina Rossetti

Christina Rossetti was an English poet who was born in 1830 and died in 1894. She wrote poems for adults and children, including ‘Goblin Market’, and ‘In the Bleak Midwinter’, which was later set to music and is still sung as a Christmas carol. She was the youngest of four siblings, all of whom were writers. Her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a famous artist and poet, and Christina modelled for several of his artworks. Her poetry was popular during her lifetime and influenced many later writers and poets. Many composers have responded to the lyrical beauty of her verse by setting her poems to music.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Empathy by A. E. Stallings

Episode 74 Empathy by A. E. Stallings A. E. Stallings reads ‘Empathy’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: This Afterlife: Selected PoemsAvailable from: This Afterlife: Selected Poems is available from: The publisher: Carcanet Amazon:...

From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer

Episode 73 From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, by Emilia LanyerMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer.Poet Emilia LanyerReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessFrom Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Lines 745-768) By Emilia...

Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani

Episode 72 Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani Z. R. Ghani reads ‘Reddest Red’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: In the Name of RedAvailable from: In the Name of Red is available from: The publisher: The Emma Press Amazon: UK | US...

0 Comments