Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 8

Beyond the Last Lamp by Thomas Hardy

Mark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Beyond the Last Lamp’ by Thomas Hardy.

Poet

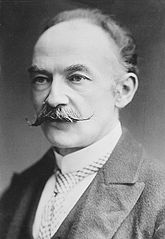

Thomas Hardy

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

Beyond the Last Lamp

by Thomas Hardy

I

While rain, with eve in partnership,

Descended darkly, drip, drip, drip,

Beyond the last lone lamp I passed

Walking slowly, whispering sadly,

Two linked loiterers, wan, downcast:

Some heavy thought constrained each face,

And blinded them to time and place.

II

The pair seemed lovers, yet absorbed

In mental scenes no longer orbed

By love’s young rays. Each countenance

As it slowly, as it sadly

Caught the lamplight’s yellow glance

Held in suspense a misery

At things which had been or might be.

III

When I retrod that watery way

Some hours beyond the droop of day,

Still I found pacing there the twain

Just as slowly, just as sadly,

Heedless of the night and rain.

One could but wonder who they were

And what wild woe detained them there.

IV

Though thirty years of blur and blot

Have slid since I beheld that spot,

And saw in curious converse there

Moving slowly, moving sadly

That mysterious tragic pair,

Its olden look may linger on —

All but the couple; they have gone.

V

Whither? Who knows, indeed . . . And yet

To me, when nights are weird and wet,

Without those comrades there at tryst

Creeping slowly, creeping sadly,

That lone lane does not exist.

There they seem brooding on their pain,

And will, while such a lane remain.

Podcast transcript

This poem has haunted me for thirty years, just as the memory of the couple haunted Thomas Hardy for thirty years, before, if we can believe him, he wrote it down.

Anyone who is familiar with Hardy’s novels will recognise this as a quintessential Hardyesque scene: a pair of lovers are in some kind of trouble, and find themselves ‘absorbed / In mental scenes no longer orbed / By love’s young rays.’ We get the sense that they are going over and over their situation together, and finding no resolution, only what Shawn Coyne calls ‘the best bad choice’.

In story after story, Hardy the novelist presents us with ways in which love’s young rays are darkened or blotted out by circumstance.

Sometimes it’s an unwanted pregnancy. Sometimes it’s the discovery or confession of another lover or even a spouse or a child. Sometimes they are separated by a class divide. Sometimes there is a crime involved, or even a simple mistake like going to the wrong church on your wedding day.

Whatever the circumstances, lots of Hardy’s characters end up in a situation like this – pacing together at the edge of town, on the margins of society, worrying at the problem together or arguing about it, or trying to persuade each other of one course of action or another.

But in the case of this poem, we don’t know, any more than the speaker of the poem knows, what is troubling this particular couple. And this is part of the poem’s power – we can only imagine what it is, or maybe project our own troubles and dilemmas, past or present, onto the couple.

And the fact that we don’t know the specific issue heightens our sympathy. I mean, if we knew what the issue was, then depending on our view of the matter, we might find ourselves taking sides or passing judgment, or explaining it away. But since we don’t know, all we can do is empathise with their suffering.

The poem also gains power from the sense it gives of being based on a real situation, an actual experience Hardy had of seeing a couple and being unable to forget them and eventually writing it down and making a poem out of it.

I can’t prove this is based on a real couple, but Hardy gives a very strong hint by inserting the words ‘Near Tooting Common’ in brackets and small print, just after the title.

Using a real place name is unusual in Hardy’s fiction – he set most of his stories in the West Country of England, where Hardy and I both grew up, but he fictionalised it, or Romanticised it, by calling it ‘Wessex,’ the name of the old Anglo-Saxon kingdom. So Dorchester became ‘Casterbridge’, Weymouth became ‘Budmouth’, and my home town, Barnstaple, became ‘Downstaple’.

But he doesn’t change the name here, he says the lane was ‘near Tooting Common’, an actual place in London, which to me is a pretty strong hint that this is a poem that began with a memory, before Hardy’s imagination got to work on it.

In another poem, ‘Afterwards’, where he basically writes his own elegy, Hardy describes himself as ‘a man who used to notice such things’, suggesting that the role of the poet is to see the things others miss, and to note them down, to memorialise them.

Only this week, you and I may well have walked past a couple just like this one, without giving them a second glance, preoccupied with our own affairs. But the poet notices them. The poet bears witness, by writing it down and repeating the tale, like the Ancient Mariner.

And the poem doesn’t help the couple. No words of Hardy’s can change their situation, any more than the words they speak to each other.

What the poem does do, marvellously, is to conjure the lane at twilight, with the rain pouring down, and the couple hovering at the edge of vision, just about discernible in the light of the last lamp. Listen to the opening stanza, doesn’t it make you shiver?

While rain, with eve in partnership,

Descended darkly, drip, drip, drip,

Beyond the last lone lamp I passed

Walking slowly, whispering sadly,

Two linked loiterers, wan, downcast:

Some heavy thought constrained each face,

And blinded them to time and place.

Hardy really goes for it, right from the beginning. Listen to what he does in the second line:

Descended darkly, drip, drip, drip,

Did you hear that? That’s right, he alliterates on every single word in the line! Not even the Anglo-Saxons took it that far! And of course, if you or I took that to a typical writing class, we’d be told to tone it down, that it was a bit too much. So thank goodness Hardy lived before the age of writing workshops.

And while I was reading this poem for the umpteenth time, and thinking about it for this podcast, I found myself noticing that phrase ‘with eve in partnership’; obviously ‘eve’ here is the poetic shorthand for ‘evening’, so he’s literally saying that the rain and evening had conspired in partnership to create the gloomy atmosphere of the scene.

But do you reckon there might be a pun on ‘Adam and Eve’ here? I think there might be, especially as Hardy was very well steeped in the language of the Bible, and very much disposed to see human beings and human relationships as inextricably bound up with misery. For example. Chapter 2 of his novel The Return of the Native is titled: ‘Humanity Appears on the Scene, Hand in Hand with Trouble.’

Anyway. Another thing Hardy does with the rhyme and metre is quite subtle at first but becomes more and more noticeable as the poem goes on.

The rhyme scheme is basically very simple – we’ve got 3 rhyming couplets, so it rhymes AA, BB, CC. So in that first stanza we have partnership/drip, passed/downcast and face/place.

But right in the middle of the stanza, something sticks out: the single word ‘sadly’, which doesn’t rhyme with anything else. It drives a wedge through the middle couplet, passed/downcast, and through the middle of the stanza. And of course it’s not rocket science to see this as mimetic of the way the sadness has driven a wedge between the two lovers.

While rain, with eve in partnership,

Descended darkly, drip, drip, drip,

Beyond the last lone lamp I passed

Walking slowly, whispering sadly,

Two linked loiterers, wan, downcast:

Some heavy thought constrained each face,

And blinded them to time and place.

I say the word ‘sadly’ doesn’t rhyme with anything else, but as we read on, we find it chiming with itself, because the same word appears in the same place in every stanza, like a bell tolling more and more insistently as the poem goes on. And we notice that each time it’s paired with the word ‘slowly’:

Walking slowly, whispering sadly,

As it slowly, as it sadly

Just as slowly, just as sadly,

And Hardy does something else with this line that makes it stand out from the others, and that’s to switch the meter from iambic to trochaic. So the poem is written in a fairly regular iambic tetrameter, so in other words it’s got four beats, going ti-TUM ti-TUM ti-TUM ti-TUM. Which makes for a fairly conventional and sedate and in this context nicely plangent rhythm.

But in this middle two lines, Hardy reverses the meter, so instead of ti-TUM ti-TUM, we’ve got TUM-ti TUM-ti TUM-ti TUM-ti. Listen for it here:

Walking slowly, whispering sadly,

As it slowly, as it sadly

Just as slowly, just as sadly,

Moving slowly, moving sadly

Creeping slowly, creeping sadly,

Can you hear that? It’s like an eddy in the stream, where the water flows back on itself in a reverse current. And to me it feels like the pang of sadness or pain or despair, that keeps coming back and reminding the lovers of the impossibility of their situation.

(Actually in the following line of every stanza, Hardy muddies the metrical waters still further by using something called a trochaic tetrameter catalectic, but I think I’ll spare you that for today.)

In the final stanza, we get to the heart of the matter. Having signalled fairly strongly that this is a poem based on fact rather than fantasy, Hardy makes a pretty extraordinary statement:

To me, when nights are weird and wet,

Without those comrades there at tryst

Creeping slowly, creeping sadly,

That lone lane does not exist.

What we have here is not a lane that exists in objective reality, but a feeling so strong that it has created a little world unto itself, where the lane and the couple and the rain falling on that particular evening are somehow bound up together. The lane’s existence depends on the presence of the couple, and as long as the lane exists, it will be haunted by them:

There they seem brooding on their pain,

And will, while such a lane remain.

Listen to the final line again:

And will, while such a lane remain.

Those last two words, ‘lane remain’ sound a bit awkward together, don’t they? A bit like he’s labouring the point with the extra rhyme from lane, when he’s already got a great clinching couplet with ‘pain’ and ‘remain’. Again, if Hardy took this to a poetry workshop he would be told to tidy it up, smooth it over, by finding an easy way to avoid the extra rhyme and make it more elegant.

But he didn’t tidy it up. He leaves it there, like a loose end, so that it catches on the ear, the way the poem catches on the heart, each time we hear it.

Beyond the Last Lamp

by Thomas Hardy

I

While rain, with eve in partnership,

Descended darkly, drip, drip, drip,

Beyond the last lone lamp I passed

Walking slowly, whispering sadly,

Two linked loiterers, wan, downcast:

Some heavy thought constrained each face,

And blinded them to time and place.

II

The pair seemed lovers, yet absorbed

In mental scenes no longer orbed

By love’s young rays. Each countenance

As it slowly, as it sadly

Caught the lamplight’s yellow glance

Held in suspense a misery

At things which had been or might be.

III

When I retrod that watery way

Some hours beyond the droop of day,

Still I found pacing there the twain

Just as slowly, just as sadly,

Heedless of the night and rain.

One could but wonder who they were

And what wild woe detained them there.

IV

Though thirty years of blur and blot

Have slid since I beheld that spot,

And saw in curious converse there

Moving slowly, moving sadly

That mysterious tragic pair,

Its olden look may linger on —

All but the couple; they have gone.

V

Whither? Who knows, indeed . . . And yet

To me, when nights are weird and wet,

Without those comrades there at tryst

Creeping slowly, creeping sadly,

That lone lane does not exist.

There they seem brooding on their pain,

And will, while such a lane remain.

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy was an English novelist and poet who was born in 1840 and died in 1928. He was best known for his novels, most of which were set in the West Country of England, which he fictionalised as ‘Wessex’, taking the name from the old Anglo-Saxon kingdom. But he thought of himself first and foremost as a poet, writing poetry throughout his adult live and continuing to publish it after he gave up on novel writing. After his death his ashes were buried in Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey, and his heart was buried in Dorset, with his first wife, Emma.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Empathy by A. E. Stallings

Episode 74 Empathy by A. E. Stallings A. E. Stallings reads ‘Empathy’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: This Afterlife: Selected PoemsAvailable from: This Afterlife: Selected Poems is available from: The publisher: Carcanet Amazon:...

From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer

Episode 73 From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, by Emilia LanyerMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer.Poet Emilia LanyerReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessFrom Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Lines 745-768) By Emilia...

Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani

Episode 72 Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani Z. R. Ghani reads ‘Reddest Red’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: In the Name of RedAvailable from: In the Name of Red is available from: The publisher: The Emma Press Amazon: UK | US...

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

Wonderful appreciation (and reading) of this haunting Hardy poem. On second hearing, while agreeing the couple did exist and were observed by Hardy, as the appreciation suggests, I also find myself identifying them as in some way linked to Hardy’s also problematic – at least at times – long marriage to Emma, his first wife. A number of poems depict them as somehow at odds, having lost the spark of love which originally attracted them, unable to resolve or undo the situation. It’s true that the novels also often depict troubled relationships, and make me wonder if Hardy’s parents – an apparently easy going father and a more exigent mother – have become a pattern for that fiction. Perhaps the couple haunted Hardy partly because of those other difficult couple relationships. But he does not ‘use’ them as surrogates – he pays them the respect of leaving them mysterious and haunting us along with the lane, The poem makes the lane exist – whether or not it has survived with Tooting common itself (which thankfully is still there).

Thanks Pat. Yes, there could well be echoes of Hardy and Emma in this poem, as well as several of his fictional couples. No doubt I will get round to the Poems of 1912-13 at some point on the podcast, plenty to talk about there… And yes, it’s great that Tooting Common ‘remains’.