Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 47

In the stillness of his moment, deciding by Tom Sastry

Tom Sastry reads ‘In the stillness of his moment, deciding’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.

This poem is from:

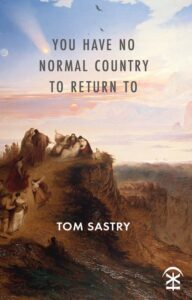

You have no normal country to return to by Tom Sastry

Available from:

You have no normal country to return to is available from:

The publisher: Nine Arches Press

Bookshop.org: UK

In the stillness of his moment, deciding

by Tom Sastry

The new kid in the fourth year was SAS.

He’d killed: three IRA in a Belfast pub.

Although untrue, this was his truth –

who he felt he was. A man. Tooled up

with me trapped in my moment

of seeing him with the gun, and him

in the stillness of his moment, deciding

if I could go on living. The same question

engulfed me last year, like a dropped sky.

I brought him and his gun back into my thoughts –

lived in that pause. The war in his head

inside the war in mine. A little nest of wars.

Interview transcript

Mark: Tom, where did this poem come from?

Tom: I think that’s a difficult question. I can tell you what it… Well, no, I’ll tell you where it came from. I think the more interesting question is why I ended up writing it at the point that I did. The action of the poem is quite simple. It’s a true story. It’s about a boy who was in my class, he was certainly in my year group, I can’t remember if he was in my class, when I was in what we then in English schools called the fourth year, which is 14 to 15. And he made an earnest attempt to persuade me that he was in fact, a British Special Forces soldier, SAS and that he had killed several members of the Irish Republican Army, the IRA in a special operation that of course, he wasn’t allowed to tell anyone about except me in the fourth year at school.

Now, on the one hand, this is an outrageous lie. It’s the kind of lie that no sane person would ever expect another human being to believe, that a 14-year-old boy had done these things. And on the other hand, of course, it’s a deeply disturbing fantasy. And, because, on the one hand, it’s clearly not true, but on the other hand, it does signal a certain attraction to the idea of extreme violence, which you do actually have to take quite seriously if someone says something like that. So, it’s both meaningless, because it’s obviously untrue and also meaningful.

And that all happened… Well, I was born in 1974, so you can probably work out…if anyone is very good at arithmetic, will work out at what sort of time I would have been at 14 or 15. And the thing that happens in the poem is that I’m looking back on this incident, speaker of my poem, and you always change yourself and other things a little bit, I think, in a poem, is looking back on this incident, and it acquires a new resonance when they’re in a point of crisis.

And for me, I mean, this is all the stuff that isn’t in the poem. For me, the significance of that was that I found myself thinking about this boy who I, hadn’t thought of for a quarter of a century, at a time when I was going through a really difficult period. And for various reasons, I was quite frightened going about my daily business because of something that was happening in my life. And there was no reason why this intrusive thought about this boy in the Britain of Margaret Thatcher, who had as many young white British children did, I think it was a very militaristic time, as I remember, it was, the army was big, and people liked the idea of being soldiers, and they liked the idea of being the state’s instrument of violence. And this was a very common fantasies, not just of teenage boys, but also of some adult men around that time. So, it’s very much about the violence of the time.

And I think when I was 25 years later, in a position where I was feeling very unsettled, I started thinking about this a lot. And it was only at that point, that the pieces fell into place, and I realized something I hadn’t actually consciously realized at the time, which was that I instinctively saw myself, not as the British citizen, that this boy was protecting with his imaginary violence, I saw myself as much closer to the… You know, I saw myself more as his prey, than as a citizen of the country that he was supposed to be defending in his fantasy. And that’s quite a profound realization about your relationship to the violence of the state, and also your relationship to the popular culture that lionizes the violence of the state in your country.

I don’t have any Irish connections at all, but, I was one of the very few non-white children in my class at school, and I suspect that has something to do with it. Again, I wouldn’t have been conscious at that time, of any similarity between my own condition, or between the way I was seen and the way in which the media portrayed what was happening in Ireland. I mean, I wouldn’t have been capable of forming that thought at that time.

And I think what interests me in the poem and actually, particularly the context of the book I published it in, which is a lot about my generation, people born around the same time, and a lot about how the historical events of my time have influenced my life and my thinking. Yeah, what really interested me was this sudden revelation of the vulnerability that I experienced in that moment and didn’t consciously recognize. So, that’s sort of the first bit of the poem and the action of the poem.

And then the other part of it is the more direct emotional side of it, which is that the poem is built around this moment, where in this boy’s violent fantasy, he is there, he is pointing a gun at someone, and I’m in the place of that someone. And he has this moment of absolute power, where he can choose what happens. And I have this moment of absolute powerlessness, or, in a different sense, a moment of complete abdication of responsibility of my own life, because I’m not making that decision anymore. And so it’s also built around the significance of that moment, and how that connects both to a fear of violence and also to suicidal ideation. So, that was where I was coming from in the poem.

Mark: So, it’s a small poem, but there’s a lot in it, isn’t there?

Tom: Yeah, it’s a terrible novel. [Laughter] You know, I mean, you’re better off reading the poem, than playing back what I’ve just said, I think that you’ll get a lot more from it. And it was initially a lot longer as you would… And the process is cutting it back to what it needs to be.

Mark: Oh, that’s a lovely way of putting the editing process in poetry, just cutting it back to what it needs to be. Because I think this is one of the things I love about poetry is the wonderful economy that you’ve got and suggestiveness, in a poem like this that’s, if you look at it on the website, folks, it’s 12 lines, 3 stanzas of 4 lines each. And yet there’s this whole world or nest of wars, inside the poem.

So, just to recap what I’m getting. So, there’s this experience at what we call secondary school here in England, and that boast, that bullshitting, that lie by that boy, it was a kind of a Rorschach ink test for the both of you because on the one level, it reveals something about his violent fantasies. But you instinctively saw yourself not as the person being protected, as the other the way that, say, the IRA, and the Irish Republicans in general, were often portrayed as the other in the media at the time.

Tom: Yes. And that was such a strong thing, I think in Britain in the 1980s, you know. The IRA were the bogeymen and women, and we were supposed to be terrified of them. You know, and so that was quite a strong… But it feels, to me thinking back to that time, quite a strong thing for someone in my position to say. It’s not like I’m consuming Irish Republican media, and therefore seeing the world from a different side. I mean, I had no contact with anything like that, so.

Mark: Yeah. And then, at the end of the second stanza, at the end of this line, you’ve got, ‘The same question engulfed me last year,’ which, as a reader, I take that to be the question of, ‘Can I go on living?’ And so, what you’re suggesting, but not revealing, is there is something happening in the present, in the now of the poem that gave you that same level of existential threat, but actually, it sounds like much more realistic. And this, I think, technically, it’d be the hippocampus in play, but it starts associating back to the last time you experienced a sliver of this kind of threat before. It’s kind of replaying that memory, and giving you the question, that it’s the heart of the poem.

Tom: Yes, yes, that’s right. And it seems like such a bizarre connection, isn’t it? Because on the face of it, it’s quite a trivial incident. You know, a 14-year-old boy tells an obvious lie. You know, I suspect we all laughed at him. I can’t actually remember. But I suspect he became notorious for these lies, and no one took him at all seriously. And he made himself marginal when he was trying to make himself big. I’m sure that’s what happened because it’s so transparent. And so from that point of view, it’s a trivial incident. And I wouldn’t have been thinking about him a lot in the intervening period at all.

Mark: Yeah. But from my former career as a psychotherapist, it makes a lot a lot of sense to me, because, on the one hand, our imagination/unconscious mind doesn’t really know the difference between something that’s imagined and something that’s real. If you’ve imagined something vividly enough, it can feel like it’s real in the memory, and the way the memory will work is by the emotional association. It’s almost as though it’s flicking back through the databanks. ‘When did we last experience this particular kind of emotion? Oh, yes.’ And no matter how absurd it might seem, and how laughable in retrospect, it’s that memory of that kid at school. So, to me, it seems that there’s a very strong emotional truth in the poem, even though it’s as you say that the link feels logically absurd.

Tom: Yes. And I think there’s something else in there for me anyway. I mean, I don’t know if it’s in there. You never know whether you managed to put something in the poem or whether it was just there for you, which is that, I think, there is a sense that the speaker of the poem is in some way attracted to the idea of abdicating responsibility for his own life. That if you, you know… That the idea that this boy is there, and he’s in his moment of power, and he’s deciding what happens, isn’t that moment quite appealing?

I mean, I think there’s actually three time periods in the poem because the poem is written… both parts of the poem, the part that happened in school and the part that happened in the subsequent crisis are in the past tense. So there’s the now of the writing of the poem, there’s the now of the adult crisis, and there’s the now of the boy’s fantasy.

So, I don’t think in the moment of writing I’m saying, ‘Actually, that was quite appealing.’ But I think I am saying that in that moment of crisis, it was quite appealing. I think that’s in there as well, that actually sometimes the idea that you are not responsible for your own life can be, you know… And it’s not, you know… I don’t think it’s a suicidal thought, but I think it is a thought that is…it’s a refusal to make the choices that are necessary in order to take full ownership of your own life, because at that moment that does not seem like a thing you can do.

Mark: And that’s a very human impulse, isn’t it?

Tom: Yeah.

Mark: To want to let go and not have to deal with whatever the thing is in front of us. And I think, maybe it’s important to underline if anybody’s listening to this and they’re saying, ‘But what was it? You know, what happened in the speaker’s life?’ We’re not supposed to know, are we? And to me, that intensifies it even more because maybe if we don’t know, then we start to imagine things, and therefore we start to emotionally associate to the speaker in the poem more than if it was something very specific that, ‘Oh, right. Well, that’s never happened to me, therefore, I don’t…’ You know, the level of association isn’t as strong, and the power of being trapped in that moment, isn’t as intense.

Tom: Yeah, I would encourage people to imagine the worst incident in a fairly ordinary life rather than something, extravagantly newsworthy.

Mark: Okay, so the speaker the poem is saying, ‘The same question engulfed me last year.’ And it is in the past tense. So, am I right in saying that the speaker is looking back on this experience of this question and this engulfment?

Tom: Yes, there is an element of recollecting in tranquility here. There’s a lot of tying up. There’s a lot of small ‘p’ philosophy in this poem. There’s a lot of reconciling with the past, and that includes the past of the previous year and these personal questions in this incident, as well as the distant past of the boy with his SAS fantasy. And actually, it was more than a year. I mean, I put last year because I quite liked the relative immediacy of it, but actually, the gap between, the second incident that was part of the inspiration for the poem, and the writing of it was considerably more than a year. And, yes, I’m all right now, and I was all right when I wrote the poem, so it’s, you know…

And I think the tone of the poem is definitely the tone of someone who’s achieved a degree of mastery over an experience by finding a way to talk about it and think about it, that puts it in its box.

Mark: Good, good. Well, that’s good to know.

And, again, you’ve talked about the speaker of the poem, because it’s very easy when we read a poem that is saying, ‘I’ to assume that this is a straight anecdote, or, relation of a story in the poet’s life. And very often, even if that is the case, that there is a relationship to something that happened to the poet, there’s a dramatizing effect of the I in the poem.

Tom: Absolutely. Well, this is editing, you can write, even if it is possible, to write a completely honest truth onto a page, which I’m not sure it entirely is, simply because you still have a standpoint, you’re still selecting whether you’re selecting details, consciously or not, you’re still telling the story from a particular point of view.

The art of particularly poetry, because it’s so distilled, and you edit so much, is that you’re making choices all the time about what you’re going to include and what you’re going to reveal and what you’re going to conceal. And those choices are based on, providing something that is very concentrated. I mean, how many words have we said about this poem? I don’t know how many words are on the poem, I guess, just looking at it on the page, probably about 70 or 80. We must have said, I imagine, you know…and we’re using thousands of words to describe it. And even then, we’re only saying a fraction of all the things that could be said, if you have an obligation to reveal all the facts.

So, that process is massively selective. And in that process, you will make choices that are for the sake of the poem, rather than for the sake of documentary truth. You know, if there is a phrase that I think makes the poem much more powerful, or much more humane, or any of the things I want to do in a poem, and it doesn’t correspond with what actually happened in the incident, I’m not going to throw my hands up in horror and go, ‘I can’t do that. I’m falsifying what happened.’ And when you live with a poem for several months, and you keep editing it, and keep honing it, the lines…but, you might start out with an awful lot that’s drawn from life and a little bit that’s drawn from the imagination. And those proportions tend to shift in favour of the imagination as time goes on.

Mark: Yeah, that’s true, isn’t it?

Tom: And sometimes it’s not even your way of imagining the incidents, it’s just the language itself wants to do something different. And I think a restriction of, witness box standards of truth in poetry would leave very little poetry standing, I think.

Mark: There wouldn’t be a lot left, would there?

Tom: Well, I mean, it depends who’s in the witness box, obviously, you know. If it’s certain former politicians, then maybe we could exceed that standard of truth, I don’t know.

Mark: Yes. So yeah, I love that idea that you start off, maybe with the intention to tell all the truth, as Emily Dickinson would have put it, but you end up telling it more and more slant, the more you work with it, the more you edit and revise, and the more as you say that the words themselves start to give you an idea where they want to go, which may well be different to what you thought you were doing when you set out.

Tom: Yes. And it’s even more complicated in a poem like this, this is a poem about a lie. You know, we know straight away, I mean, I don’t want to speak on behalf of your listeners. But I would imagine that the reader that doesn’t immediately recognize that a 14-year-old boy claiming to be a Special Forces soldier is a liar is an unusual reader. So, there’s no mystery about the fact that the central claim being made is a colossal fib. And that’s interesting as well because I think there’s something here, I know, I’m really not quite answering the question about the meaningful lie, about, the way stories are told, the way claims are made, the way the information we draw from the world and from the things that we say and other people say, isn’t just based on the assumption that they’re true, it’s based on something else that they’re telling us.

Mark: Yeah. And, okay, you’ve mentioned a few times that a lot of editing went into this, that it was longer than what we have on the page. Could you maybe just talk us through that writing process? What was the first draft like, and how did you arrive at what we have on the page or the screen?

Tom: I don’t remember exactly what the first draft… I know it went onto the second page. And I know, given the fonts and spacings I have on my computer, I mean, it would be at least 30 lines long. So, considerably more than twice its current length, maybe three times. And I think it would have told more of the story as I’ve outlined it. And that’s unusual for me, actually. I mean, most of my poems will end up shorter than their first drafts.

But that level of, to lose, 60 to 75%, of the length of the original poem is actually quite unusual for me. I might lose that much of the material, but normally, I’m filling other things in, I’m seeing opportunities to fill that space with something.

And this one, I really wanted to get the focus away from the story and towards what that moment, that moment of power, where one person has a gun, and the other person is powerless, what it means to all the people involved, to the two 14-year-old boys in the poem, to the speaker was an older adult. I really just wanted to get that right at the heart of the poem. And you always start out feeling that this will make no sense unless I explain exactly what’s going on. And I think it’s always, as we all, I mean, and goodness knows, this is, like many people of my age and gender, I’m fond of explaining things. And part of that is rooted in an anxiety that if I don’t explain everything, nothing will be understood. And poetry is one of the few areas where I actually get to edit out all my explanations, and hopefully, leave myself with what said.

But I really wanted that silence at the heart of the poem. And that was, what was behind the choice to make a cut. I think, the line in the middle of the poem because I think it is, although it’s the third of four lines in the middle stanza. But actually, I think, if you do a word count, it’s pretty much bang in the middle. And I made that the title. And that’s because I really want this focus on this stillness on this moment of decision, and this moment where things can go either way. And that just felt like a very important thing. And I think I’m not sure I understood why it felt important when I found it. But, yeah, so I edited around that moment, and its significance.

Mark: I mean, that’s such an important principle in editing a poem particularly is what is the one thing that I really want this poem to do? And for you, it became more and more obvious, it was focusing on the stillness of his moment, of that moment. And I guess that’s the ultimate existential point, isn’t it? Well, there’s two people facing each other and one of them is going to decide if the other one can continue to exist. I mean, it’s hard to imagine anything more compelling than that.

And, obviously, as you said, this is a lie, and the whole poem is kind of spun around the lie. But of course, we know that people have experienced this moment over and over far too many times, and sadly it’s still happening as we speak. And that question about explaining, did you do the thing of seeing how much can I take out and it will still make sense? And then do I have to start putting things back in again if it starts to fall apart?

Tom: Yeah. Sometimes you take something out and you have to put something else in. You know, sometimes you take something out, and it enables you to take another thing out. Because if the poem ends on Monday and you take out the bit about Wednesday, you can also take out the bit about Tuesday. That’s a crude chronological point. But that also applies in lots of other ways as well. Sometimes when you lose something, it actually creates an opportunity to lose something else.

And I think some poems are, they’re kind of bimodal. You know, some poems don’t have one centre, some poems are about the kind of jangle that’s created by the fact that we’re pursuing so many things at once. I think a poem which has stillness at its heart, whatever that stillness, whether it’s a stillness of peace or stillness of terror, in this case, I think it has to be about one thing, because the more things you introduce, the more notes you introduce into it, the less stillness there is and you lose that.

Mark: I think you’ve got this extraordinary thing, ‘The war in his head, inside the war in mine, a little nest of wars.’ So, the way I’m reading that is… I remember thinking, when I first read it, it’s not the war in my head opposite the one in his. So, if you’ve got two people facing each other, you could say that the wars are opposite each other because their heads are facing, but it’s actually you remembering the war in his head, and so therefore, it’s inside of yours. It’s like a little Russian doll set of memories, and you’ve got this little nest of wars, which is a just… I don’t know, to me that it’s so concentrated and it’s so crushing, the idea of us being inside these, wars, inside wars, inside wars. So it’s quite a horrific image, at the same time, it’s really, really clever the way you’ve done it. I mean, how did you get to that ending?

Tom: I was struggling, because I can’t even remember the ending that I deleted, but I had an ending and I didn’t like it. Even by the time I first submitted this poem, in my manuscript to my publisher, Jane Commane, at Nine Arches, I think it was 18 lines long at that point, so 50% longer than it is now. And she marked it as one that didn’t need to go, that I might consider dropping from the manuscript.

And I had a strong attachment to it by this point. I thought, ‘This poem is doing something that I want in the book.’ And that’s partly to do with the scheme of the book and the themes of the book. It’s quite central to it. This idea that these incidents in otherwise, ordinary lives can really illuminate something about the way that the mark, that the history that we’ve lived through leaves on us can actually influence our lives. It just seems so germane to that, and that’s sort of the thing that the whole book is circling around.

And partly, I just thought that was a really good poem in there, I thought I wasn’t prepared to lose it. But I took the challenge, and I went back to it. And I came up and I thought, ‘Okay, this is going to come down to three stanzas, I can feel it.’ You know, I didn’t know it was going to be three stanzas, I knew it was going to be sort of somewhere around that number of lines. And I knew that line, ‘In the stillness of his moment deciding,’ was going to be in the middle, and it was probably going to end up as the title. And I had to cut a lot off the end. And I was looking to get there as quickly as possible.

And the technique that I use too much, I’ve got a real weakness for it, is an end rhyme at the end of a poem, which otherwise doesn’t have a lot of use of rhyme in it, which is what… And I do it because I think a rhyme really gives you nowhere to go. You know, a really strong end rhyme doesn’t actually give you an… You know, unless it’s a comic piece, and you go…

There’s a finality to it and I wanted the finality to it because I thought that’s going to make people stop, and then it’s going to make people ask why I’ve stopped there. And so I had that lived in that pause. And then when I wrote, ‘The war in his head is not the war in mine,’ I knew I had a few syllables left to play with. And I do remember sort of scratching my head as to what could go in there, not knowing that it was going to rhyme, but thinking, ‘Well, that would be nice.’ Especially if there’s a kind of half-rhyme with mine there, as well. So you kind of, like, another rhyme there just really rounded off.

And then I think I came up with wars first, and then the nesting idea just seemed…that was fortuitous. It was because, I was just thinking about, I don’t think I even realized that about nesting dolls and nest in that sense, but I think I just came up with a word, and it was a kind of left field word choice. And I thought, ‘Oh, oh, no, that actually makes perfect sense.’ Sometimes you just get lucky.

Mark: So, I love the fact that you took that feedback from Jane as a challenge, that really she was indicating that it’s not really coming across strongly enough to keep it in the collection. And you decided, ‘No, I’m going to go into bat for this poem, and I’m going to show what’s there.’

Tom: I think it’s a bit of a cliché, I think a lot of editors will tell you this, as well as poets, most editors, are poets. Jane is a very fine poet. But people often say that an editor or a critic, or someone commenting in a…in a peer commenting in a peer mentoring group or anything like that, people are generally very good at telling you when things aren’t working, and they’re not so good at telling you what you need to do to change it.

So, yeah, I mean, one of the first pieces of advice you’ll get, as with all advice, even good advice, it’s not universally true, is take people very seriously when they say something’s not working, don’t necessarily take them so seriously, when they say, ‘What you need to do to fix it is X, Y, and Z.’ Because what people are trying to do is they’re trying to take something they haven’t quite connected with, and then turn it into something they can connect with, which means it’s not your poem anymore if you do that.

And so, I don’t think Jane made any particular specific suggestions on this piece because I think, her recommendation was that it shouldn’t remain in the collection. But I knew I didn’t want it in the collection if she wasn’t confident. I wasn’t going to say, ‘No, you know you’ve got that wrong.’ And I could kind of see that it wasn’t quite doing what it needed to do.

But the thing I know is that there’s something that obviously a reader or an editor doesn’t know is that I think there is something you kind of get a sense, I think that there’s something just out of reach that isn’t that far away, and you can do it. And no one else knows which of your unsuccessful poems are just a short distance away from being something that you’ll be really proud of, and which of them are just poems that you need to scrap. Because that’s a feeling you’ve got that there’s something just out of reach that you can actually get to, and no one is going to be able to spot that for you. You just have to trust that feeling.

Mark: Well, absolutely. And I’m glad you did, Tom, because, as I said, it’s a small poem with an awful lot in it. And it really does is repays a lot of repeated listening and re-reading. So, I think this would be a good time for us to hear it again, in light of what you’ve just said. Thank you, Tom.

In the stillness of his moment, deciding

by Tom Sastry

The new kid in the fourth year was SAS.

He’d killed: three IRA in a Belfast pub.

Although untrue, this was his truth –

who he felt he was. A man. Tooled up

with me trapped in my moment

of seeing him with the gun, and him

in the stillness of his moment, deciding

if I could go on living. The same question

engulfed me last year, like a dropped sky.

I brought him and his gun back into my thoughts –

lived in that pause. The war in his head

inside the war in mine. A little nest of wars.

You have no normal country to return to

This poem is from You have no normal country to return to by Tom Sastry, published by Nine Arches Press.

You have no normal country to return to is available from:

The publisher: Nine Arches Press

Bookshop.org: UK

Tom Sastry

You have no normal country to return to (Nine Arches Press) is Tom Sastry’s second collection of poems, and it is political, ironic, emotional, morbid and funny in all the wrong places. It follows A Man’s House Catches Fire (2019) which was highly commended in the Forward Prize and shortlisted for the Seamus Heaney First Collection Prize, and the pamphlet Complicity (2016) which was a Poetry School Book of the Year and a Poetry Book Society pamphlet choice.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Empathy by A. E. Stallings

Episode 74 Empathy by A. E. Stallings A. E. Stallings reads ‘Empathy’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: This Afterlife: Selected PoemsAvailable from: This Afterlife: Selected Poems is available from: The publisher: Carcanet Amazon:...

From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer

Episode 73 From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, by Emilia LanyerMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer.Poet Emilia LanyerReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessFrom Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Lines 745-768) By Emilia...

Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani

Episode 72 Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani Z. R. Ghani reads ‘Reddest Red’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: In the Name of RedAvailable from: In the Name of Red is available from: The publisher: The Emma Press Amazon: UK | US...

0 Comments