Podcast: Play in new window | Download

No Tengo Mas

by Mick Delap

for Anna and Ian

“With this ring…” – and down four hundred years

the voice of the giver plucks out the words

engraved inside its hand crafted golden circle:

no tengo mas que dar – I have no more to give you…

It should go on, except my heart –

no tengo mas que dar te, pero mi corazon:

I have nothing more I can give you, except my heart.

But the ring with its clasped hands was too small

for all the words, and she never had a second chance.

His Girona was rushing to join Spain’s Armada, sailed late

for England, glory – and the shock of the Channel battles.

Drake, the fire ships, storms, and helter skelter flight,

he survived them all: the struggle to weather Scotland,

the break out, north-about, into the Atlantic.

But turning south at last, round Ulster, just as he dared

to start dreaming again of light and warmth and home,

their luck ran out. In the dark of a late October northerly

the Girona struck Lacada Point, and the high sea

clasped every soul on board to its cold, breaking heart.

We don’t know his name, only his ending.

About her, nothing – except that golden ring,

lying now full fathom five, washed by the tides

deeper each day into the changing months and years.

Four centuries on, divers found it encrusted

in seagrowth, prized it loose, and brought it back up

– rich and strange – to emerge unchanged:

No tengo mas… I am nothing, except in giving.

Perhaps it says, giving myself to you has made me.

But it could be, I have never given everything;

even an unvarnished, I have nothing more to give.

Each ring hammers out its own conclusions,

and something gleams from the ashes, endures the collision

between our joys and losses. No tengo mas que dar –

being and giving is what we are.

Interview transcript

Mark: Mick, where did this poem come from?

Mick: Well, in one sense, it came from an exhibition room in the Ulster Museum in Belfast because I’d gone over to Belfast with an early draft of my book, Opening Time which didn’t at that point have this poem in it to get some editorial advice from the very fine Irish poet, Sinéad Morrissey. And in between the first time I’d talked to her and returning to talk more with her, she said, ‘Why don’t you pop next door to the Ulster Museum?’ So, I did. And I was very excited because I was brought up with the stories of the Armada, the Spanish Armada back in 1588. And I was brought up by the sea in a naval port, Portsmouth and the stories of the Armada were very fresh. And then as I developed in my early, early adulthood, developed more and more interest in the sea. The first of the Armada ships that had been wrecked on the way south… on the way fleeing around Scotland and then fleeing south down the Irish coast, the first of those ships to be found by divers and excavated or whatever you call it… investigated was the Girona up by Giant’s Causeway in the northeast of Ulster.

And I’d loved that story. I’d seen the pictures. And so going into the room in the Ulster Museum where all the artifacts from the Girona was a terrific thrill. But the best thing of all was this tiny, little ring, this tiny, golden ring which was there. Very humble ring. Rather crudely made. And I thought, ‘That is fantastic.’ And I went back to talk more with Sinéad Morrissey and I showed her… there was a postcard and I showed her a postcard. And she said, ‘That’s a poem.’ And I said, ‘Get off. It’s mine!’

Mark: I saw it first!

Mick: Absolutely. [Laughter]

Mark: Yeah. Beautiful. So that was quite an intervention from Sinéad Morrissey, wasn’t it?

Mick: Yes, it was. It was. And she contributed, I think, greatly to the early draft of my collection. But it was rather strung out in finding and pushing through the actual printing of it. So, I was able to put in some later poems. And of course, this is one and it starts off the collection.

Mark: Okay, so that’s the activating event, the trigger, if you like, but what did it trigger in you, Mick? Because I can tell that there’s… I don’t know. There’s something for you in all of this.

Mick: I think you’re absolutely right. I mean, I came to poetry late. So, I was writing this in my mid, getting on to what’s my late sixties. All my life I had loved sailing and in my sixties I bought my own small boat and was sailing the west coast of Ireland and the Coast of Ulster. So, I was getting more and more into the feel of the coast and the stories of the coast. So that was one thing it triggered, a sense that this was a coast with a history, a very interesting, often tragic history. And that spoke very much to the sailing in me, if you like.

I’ve already said that I found the Armada a very romantic episode in English history although it’s seen rather differently in Irish history. Very often the Armada survivors came ashore and were actually massacred by English soldiers. So, there is a slightly different take. But also, it spoke, I think, to me of… as I was, in a sense, looking back at a lifetime of affections and of loving, it spoke to me about how important relationships are. It sounds very hackneyed but how important it is to engage in relationships. And this seemed to be a story about engaging, about taking that step towards someone else.

Mark: Right. Beautifully put. And so just so we can nail down the historical scenario, the Spanish Armada came to invade England in 1588.

Mick: The south coast of England.

Mark: Yeah. So, they sailed up along the south coast of England…

Mick: Yep.

Mark: Then, you know, they were fighting their way along, got defeated. And then they had to go up around north of Britain and then they ended up… this was on the route home.

Mick: This is on the route home.

Mark: The route home and you’ve got this lovely moment in the poem where just at the end of the line you say, ‘Turning south at last round Ulster just as he dared.’ And that’s the end of the line. And then the next line, ‘to start dreaming again of light and warmth and home.’ And then the next line, ‘their luck ran out.’ So, this is when he ran ashore?

Mick: Yep, yep.

Mark: And presumably, this would’ve been an engagement ring?

Mick: Certainly some kind of promise, isn’t it? The Irish still use them. They call them Claddagh Rings and they’ve got a clasped hand and then you can engrave a name on it or you can engrave a promise. And I suppose this is a promise: ‘I have nothing more to give you except my heart. I am giving you my heart.’ And he sailed away presumably a young soldier. We don’t… we know nothing about them. But these were two people and he was wearing a ring in which she had promised him affection.

Mark: Well, one thing I will certainly do is in the show notes I’ll put a link to some historical background on the Girona for anyone who’s interested. If we can find a photo online of the ring, that would be the icing on the cake. And so, this quotation, Mick, ‘I have nothing more to give you except my heart.’ You say, ‘It should go on except my heart.’ Does that mean it’s a well-known phrase in Spanish?

Mick: Yes. As far as I can tell from basically looking at the beginning of the quotation, it is a known romantic declaration, if you want to put it that way. So, I don’t think… probably the woman who was giving the ring invented it. I think it was one of these known ways of expressing your affection.

Mark: And is it possible that there was another ring that she had that had the other… it’s just occurring to me as we talk, that had the completion of the phrase on it?

Mick: That hadn’t occurred to me either but you’re absolutely right. I mean, this is a mutual… the exciting thing about love is that it is mutual. Sometimes not! When you get into complications…

Mark: But that’s the aspiration, at least in the beginning!

Mick: We won’t go there. [Laughter] But yes, I think it’s entirely possible. I’d never thought of that. Certainly no one has ever been able to identify his name or to work back as to who she might be. And as far as I know, nobody has ever fought to try to identify the twin ring.

Mark: Right. I mean, that… you would be some archeologist if you did that, wouldn’t you?

Mick: Well, it would be a wonderful… now in four centuries, it would be a wonderful series of connections.

Mark: Right. But in a way, the fact that we’ve just got this tantalizing half of the phrase is what makes it perfect for a poet, right?

Mick: I think it does not just because it allows you to play around a bit but also because it mirrors the situation. You have the heart… one half of a couple alive, the other half dead. So, it is about the failure to complete the circle.

Mark: Gosh, yes. In more sense than one.

Mick: In many senses.

Mark: Because the others… you know, the lucky ones on the fleet did complete the circle. I mean…

Mick: Yes, they did. And a number of ships did get home.

Mark: But this was… obviously I did a little bit of reading up on this before we came. There was a tremendous loss of life on the ship, wasn’t there?

Mick: Yes. There was. And it’s a… where she came ashore, was blown ashore, it is a dangerous shore line if you’ve got a northerly. You’re at the foot of cliffs. You have very little chance of survival.

Mark: And are you saying you have actually sailed this yourself?

Mick: I’ve sailed along that coast, yes. That particular bit, I sailed along. I have a small, rather old-fashioned boat or I did have then and I often sailed her single-handed and I was single-handed for that stretch. I was heading from Portrush towards Rathlin Island and that’s where you start getting into the North Channel that separates Ireland from Scotland and it’s a place of strong tides and where you have strong tides, the winds can interact with them in a very violent way and you have steep cliffs, rocky outliers. Not an easy coastline at all.

Mark: And so how does it feel to be sailing on there single-handedly? Presumably, knowing the history.

Mick: It… you have a mixture of emotions. There’s a constant alarm bell ringing in your mind when you’re sailing. You just, you know, mute it but nonetheless, ‘I’ve got to watch out for myself here’. But then there’s also all the other things. There is the joy of getting a boat to move in a way you want it to. And there is the enjoyment of being part of a natural world in a natural way. So, you’re part of tides, you’re part of cliffs, you’re part of sea life and you’re not using a motor. You’re using a natural force, the power of the wind.

Mark: You know, it strikes me that you would really have to be a sailor to write this poem. And throughout the collection actually, this is one of the things that I noticed. You know, there’s a lovely… because you’ve got quite a lot of poems about sailing and the view from the sea. And there’s one line in another poem, ‘Seen from the sea, it’s different.’ And it struck me that what you were giving us is the opposite view that we used to have because… There are a lot of poets in Ireland. A lot of poems have been written in and by and about Ireland. But usually what we get is the view of landlubbers like me. So, you know, the hills and the valleys and the streams or at best, from the sea’s point of view, standing, looking out to sea.

But a lot of the perspective you present in the poetry in this book are what it looks like from the sea, how the land looks like from the world of the sea and you’ve got some amazing descriptions of seas. I mean, how did that inform you in terms of the writing of this?

Mick: Well, I think you’re absolutely right. There’s wonderful poetry about the power of the sea. There’s wonderful poetry about the sea shore. There’s much less poetry written from the point of view of what it is actually like to be out on the sea in a boat which is at the mercy of the sea, which is taking advantage of everything the sea can offer. And I think that it has been a real joy to try and express some of that feeling. And clearly, this poem, although it’s not about my own voyage as some of the other poems are, nonetheless is deeply informed by the sense of what it is like being on a dark night when the wind’s getting up. You’re not sure whether your anchor is going to hold and, in their case, it didn’t.

Mark: Yeah. I mean, I’m also almost getting the sense that this is… this could’ve been written by a lucky survivor.

Mick: Yes. It is. Yes, it is about what it is like to come safely ashore or not. And I suppose I… I think I probably wished he had come ashore and wanted to allow him a voice in a way.

Mark: Yeah, that’s it because there is such longing and heartbreak in this poem and it’s like the movie that you know has the sad ending but you want to… you’re still rooting for the couple right to the end and then you know it’s not going to happen, it’s not going to turn out right.

Mick: Yes, I think that is… I’m not sure I’d thought of that before. Very often when you’re asked about a poem, you discover things about it that you hadn’t realized. But I think that’s very true.

Mark: And okay. So, you went to the museum. Sinead gave you the poem. You made sure it was your poem and not hers. What happened then? I mean, how close is what we’ve got here on the page to the initial draft?

Mick: The second stanza giving the narrative of the Armada’s progression around the coast and what actually happened, that hasn’t changed very much from the initial. I had difficulties trying to get it started. I was initially offering it to my sister-in-law, Anna who was about to marry Ian and I thought I needed to put a bit of their story in and realized that if it was going to be offered to them, it needed to be actually much more focused on the Girona story. So, the beginning was a bit tricky.

And then I always have trouble with endings. The third stanza about how the ring went to the bottom of the sea, how it emerged again, I overwrote and had to cut out a lot of excess verbiage. That pretty much was the direction in which I was going. I couldn’t get the ending right. I could get the idea that there might be different interpretations in different lives to what those words represented that I could get as a… I think probably as someone in their sixties who had been through various ways of affection, myself and love, I could see how each life goes in its own direction. I couldn’t quite work out how to end it.

I usually overegg endings and gradually, I paired it away and eventually came to what is not a quote from another poem I am very fond of but is very much influenced by it. And that’s a poem by the English poet Philip Larkin of the sixties and seventies and eighties and it’s his poem. One of his most famous poems but actually probably slightly misunderstood, I think. It’s ‘An Arundel Tomb’ and he ends up, ‘What will survive of us is love.’

Mark: Yes.

Mick: And he’s actually questioning that statement quite a lot in the poem. Nonetheless…

Mark: Yeah. It’s not as full-throated as it sounds out of context but…

Mick: But he does come back to that, eventually comes back to that affirmation. And I think a lot of us who… particularly in our younger days when we were looking for poems about love, we did look at that poem and think particularly that ending is very moving. And although it wasn’t directly in my mind, I think it very strongly influenced the way that the poem finally ended up.

Mark: Well, I think you’ve done a beautiful job with the ending, Mick. And the Romantic image of poetry is it all comes out in one glorious effusion and we never have to touch anything. But what’s… well, certainly in my experience and a lot of the poets that I’m talking to for this show is… very often it’s about patience and… of sitting and waiting and questioning the first thought and being very sensitive to when it isn’t right.

Mick: I think that’s very true. I’m actually… I need help with that process. I found that often I can work out what needs to go but more often I rely on the suggestions of fellow poets. I’ve always found it enormously helpful to have a group of close poet friends who you can share drafts with. And I have… I’m lucky to have such a group now. I helped bring it into being about 12, 15 years ago and it’s been a great strength for me. And one of the things it does is to alert me. I don’t always agree with what’s suggested but often I go away and mull it over and think, ‘Yes, they are right. That line’s not necessary. Yes, the poem should start a bit later than I’ve started with it. It’s too complicated. Yes, the poem should end there, not go on and try to keep repeating what you’ve already actually established.’

Mark: And one thing I notice is you’ve got that wonderful rhyme at the end. And, you know, for the most of the poem, it’s not rhyming. It’s like a free verse kind of equivalent of blank verse which I think is perfect for telling this story.

Mick: Yes.

Mark: But you get a bit of lift-off at the end, don’t you, with that, ‘No tengo mas que dar – / being and giving is what we are.’ You know, that really clinches it and it’s in… Oh! this has just occurred to me. That’s where the two halves come together, isn’t it?

Mick: Yes, I suppose it is. That’s a lovely thought.

Mark: You could say that.

Mick: That is a lovely thought, Mark. Yes.

Mark: Well, let’s say that that’s what it is. But also looking back, you know, before that, the previous line before that, you’ve got ‘conclusions’, and ‘collision’, which is almost rhyming, not as full. And then before that you have got ‘given everything’, and then ‘giving’ in the previous stanza. So, it’s almost as though the rhyme is revving up as you get closer to the end. Was that a conscious decision or is it just… ?

Mick: I don’t think so. I do love internal rhyme, rhymes that don’t necessarily come at the end of each line but which… the music plays from one line to the next or two or three lines further on. And I tend to… I very rarely do that consciously. I will sometimes look for another word that I feel is going to have more music in it. But it… I find it’s a fairly unconscious thing.

Mark: Well, it’s a wonderful instinct towards the end. It really gives it a lift. And you mentioned Larkin which I hadn’t spotted. The thing… you know, the poet that I picked up was Shakespeare, right?

Mick: Yes.

Mark: The Tempest, you’ve got ‘full fathom five’, and ‘rich and strange’. How was The Tempest hovering in your imagination as you were writing this?

Mick: I think that’s… it’s such a wonderful… it’s ‘Ariel’s Song’ in The Tempest when the sort of the sprite, the elf is leading the king’s son astray by singing this song. And I’ve always just loved the concept of sea change, the way that the sea turns things into something else. And when I got to that point, it just seemed… it just quite… I didn’t consciously say, ‘I’m going to quote.’ It just flooded in in a way. But it… those are favorite lines of mine.

The other thing of course about that is… and again, it wasn’t conscious but it feels fitting is that a young Shakespeare would’ve been in London during the Armada episode. And I would imagine was fairly deeply influenced by it. So, it… looking back, it feels entirely right that if you’re writing about the Armada in the 16th century that Shakespeare somehow finds his way into…

Mark: Absolutely. I mean, it would’ve been a national crisis, something that everybody lived through together.

Mick: Absolutely. Yes. Yes.

Mark: And I guess now I’m looking at it. As we talk, I’m looking at the line endings. Another… the ending of the historical, second verse, paragraph talking about the sea, ‘Clasped every soul on board to its cold, breaking heart.’. And I think that is such a devastating phrase, ‘its cold, breaking heart’. Because if it were a human heart that were breaking, it would be… there would be a warmth in it. There would be love.

Mick: Yeah, yeah.

Mark: The way you’re describing, it’s not ‘the sea’s heart breaking’. It’s ‘the heart of the sea is breaking things’. And so, it’s cold and it’s crushing but it’s the opposite of what we would associate a heart with.

Mick: Yes. I think that’s absolutely right. The sea is not a sentimental place at all. The sea is not a sentimental force. It goes its way and you… it won’t love you, it won’t hate you. It just goes its way. It’s an impersonal, immensely powerful force. And you mix with it at your peril. And it has great rewards too. It is… it can be a magic place but it is magic and it is perilous to its own way and in its own way. It doesn’t take account of us which is why it’s so tragic, of course, with global climate change, that we are affecting not just the land but we are, in major ways, affecting the sea too.

Mark: Well, Mick, I really think you’ve done a terrific job with this. You know, looking into that cold, breaking heart of the sea and plucking such a beautiful poem from it. So, thank you very much for sharing it today. Maybe this would be a good point to hear it again.

No Tengo Mas

by Mick Delap

for Anna and Ian

“With this ring…” – and down four hundred years

the voice of the giver plucks out the words

engraved inside its hand crafted golden circle:

no tengo mas que dar – I have no more to give you…

It should go on, except my heart –

no tengo mas que dar te, pero mi corazon:

I have nothing more I can give you, except my heart.

But the ring with its clasped hands was too small

for all the words, and she never had a second chance.

His Girona was rushing to join Spain’s Armada, sailed late

for England, glory – and the shock of the Channel battles.

Drake, the fire ships, storms, and helter skelter flight,

he survived them all: the struggle to weather Scotland,

the break out, north-about, into the Atlantic.

But turning south at last, round Ulster, just as he dared

to start dreaming again of light and warmth and home,

their luck ran out. In the dark of a late October northerly

the Girona struck Lacada Point, and the high sea

clasped every soul on board to its cold, breaking heart.

We don’t know his name, only his ending.

About her, nothing – except that golden ring,

lying now full fathom five, washed by the tides

deeper each day into the changing months and years.

Four centuries on, divers found it encrusted

in seagrowth, prized it loose, and brought it back up

– rich and strange – to emerge unchanged:

No tengo mas… I am nothing, except in giving.

Perhaps it says, giving myself to you has made me.

But it could be, I have never given everything;

even an unvarnished, I have nothing more to give.

Each ring hammers out its own conclusions,

and something gleams from the ashes, endures the collision

between our joys and losses. No tengo mas que dar –

being and giving is what we are.

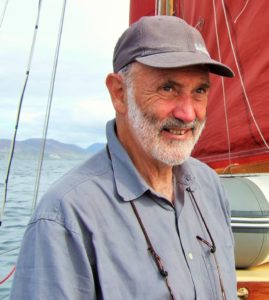

Mick Delap

Mick Delap came to poetry relatively late on in his 30 years with the BBC World Service. He is the English raised son of an Irish father. A founder member of Magma Poetry magazine, he published his first collection, River Turning Tidal (Lagan, Belfast) in 2004, and his second collection, Opening Time, (Arlen House, Dublin) in 2015. He is an active member of the workshop, Nevada Street Poets. The sea fascinates him, as an accomplished single-handed sailor; and the natural world, and now the climate emergency, are also constants. As he approaches eighty, old age and its late challenges both intrigue and inform his own practice.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Empathy by A. E. Stallings

Episode 74 Empathy by A. E. Stallings A. E. Stallings reads ‘Empathy’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: This Afterlife: Selected PoemsAvailable from: This Afterlife: Selected Poems is available from: The publisher: Carcanet Amazon:...

From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer

Episode 73 From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, by Emilia LanyerMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer.Poet Emilia LanyerReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessFrom Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Lines 745-768) By Emilia...

Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani

Episode 72 Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani Z. R. Ghani reads ‘Reddest Red’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: In the Name of RedAvailable from: In the Name of Red is available from: The publisher: The Emma Press Amazon: UK | US...

0 Comments