Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 56

‘As I push the door’ by Harry Man and Endre Ruset

Harry Man and Endre Ruset read ‘As I push the door’ and discuss the poem with Mark McGuinness.

This poem is from:

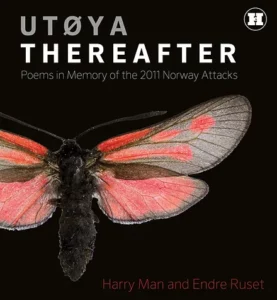

Utøya Therafter

Available from:

Utøya Therafter is available from:

The publisher: Hercules Editions

The Norwegian edition, Deretter, is available from:

The publisher: Flamme Forlag

CONTENT WARNING: the poem in this episode was written in response to the 2011 Norway attacks. There is no graphic description, but this is a sensitive topic, so please bear this in mind before deciding whether to read further, or to listen to the podcast recording.

‘As I push the door’

by Harry Man and Endre Ruset

As I push the

door, the hollow of your

guitar, newly sewn with a spi

der’s web chimes a brok

en chord. Some day

the Sun will absorb

the Ear th. Grief,

like music, p ossesses

us. I run

a finger

over the

surfaces

both of us

have to

uched; your

heights on

the door,

the neck of

your guitar,

your songs

in this room

now rest

as snow

at the window.

Norwegian version

Når jeg åpner

døra, klinger hulrommet

i gitaren din, nylig sydd med spi

ndelvev, fra en ødelagt

streng. En dag vil

sola slu ke jorda.

Musikk holder

tak i oss. Jeg stryker

en finger

o ver ov

erflaten

begge av oss

har ber

ørt, høy

den din

på døra,

gitarhalsen

din, sangene

di ne hviler i

dette rommet

som snø ved

vinduet.

© Harry Man and Endre Ruset 2023

Interview transcript

Mark: Harry, Endre, where did this poem come from?

Harry: Well, I think we’d started by thinking about how do you respond to a series of events that seem so chaotic and so senseless and trying to understand where do you even begin for something that has such little explanation behind it .

So, the whole sequence was about two attacks that took place on the 22nd of July 2011 in Norway, the first of which was a bombing in Oslo. It was a 950-kilogram fertilizer bomb, which the perpetrator drove into downtown Oslo into the government quarter, and detonated, at which point they switched vehicles, dressed as a police officer, drove about 20 miles north to the remote island of Utøya, which is home to the Labour Party’s Youth summer camp, which is the labour youth wing for the AUF in Norway. And they were having a summer camp there, mostly teenagers. He took the ferry across to the island, armed with a pistol and a rifle, and then began shooting. And it was one of the worst mass shootings in European history.

To then think about how you can write poetry in response to what was both a national tragedy, a shocking tragedy, and something that was an international tragedy was extremely, extremely difficult. Looking back at the amount of media that was already around at the time, which was sort of dramatic recreations, plays, television programs, documentaries, films, and even fiction, there was so much that had been covered where they were looking at a framing chronology to kind of pathologize why it had happened. And at that point, the focus of attention had been on the perpetrator with that chronology, and those two came together.

And I think what was quite incredible is Endre wrote a poem called ‘Prosjektil,’ which was really a statement to the effect of looking at what this had been like for the victims and the depths of the injury. At the time, it was very unusual as a crime because not only had we didn’t have vocabulary at the time. People didn’t talk about incels, or misinformation, or fake news, or conspiracy theories hadn’t made that leap from political satire to political strategy. It just hadn’t happened. And so it made it even more incomprehensible.

And there was a very public trial, and it was very rare to have a mass shooter who was caught alive and they had a chance to interview. So, at the trial, which took place in 2012, it was televised on NRK, which is the Norwegian equivalent to the BBC and they read out the indictment document. And court pathologists were brought forward to explain what had happened to each individual who had died. And at that point, the audio from the program was cut, so it was censored from broadcast. The material was seen as too graphic, and this graphic censored material really was the only kind of handrail to hold onto because it was the thing that showed, actually, what is left behind when the large scale of the attack did not match at all the small-mindedness of the motivation.

And so the only thing that was left to think about was, what does this injury mean? And that’s where Endre’s poem came in, I think, to answer that. And it was extremely moving, and now it’s become taught on the syllabus at a number of universities in Scandinavia. And so Endre came to London to Poetry Parnassus in July 2012 and presented the poem. And really, from there, it was a question of what else can be added? What else can be said? Yeah. Is that roughly how you see it, too, Endre? Has that been your experience with it?

Endre: Yeah, I think one thing that’s important to mention is that the poem that we read is actually shaped after the shadows of the victims. So, every poem in this book, except from the middle part, comes to you as kind of, like, a shadow of a face, a shadow of victim, which is very extreme, but at the same time a very effective way to present the poem.

So, this poem that Harry and me read is, it’s basically a very simple poem about grief and about missing someone. I think it’s a very unusual poem to pull out of the collection, but I’m very happy that it has been because it’s a very basic poem about what someone who goes away leaves behind. So, this poem is very classical in a way. It’s a very classic poem about grief and about losing someone you love.

And what is I guess is a little bit different with this project, is that I have a long story about the 22nd of July and Utøya and the tragedy that struck our country. But this is not, first and foremost, a personal book. It’s a book where we have taken on victims and casualties from this tragedy and kind of tried to shape this poetry in a kind of grief poetry tradition.

And so this poem here, I guess you hear about this cobweb and the guitar. Like, the guitar is a symbol also of Utøya because kids have been going there every year until this year to celebrate political ideas, social Democrats. And the guitar is always the kind of instrument that are being played around the bonfire of Utøya. So, this island where these poems are kind of extracted from, this has been, the safest place on earth, the place where kids go to start their lives being politically active. So, the poem kind of goes back to that. It’s about losing someone you love. And, yeah, I don’t know what else.

Mark: Thank you. Could I just come in and just ask a bit about the chronology of the writing process here? Because I want to come back to this specific poem in a minute. But, Harry, did you say that ‘Prosjektil’ was the first poem that Endre and you had written?

Harry: Yeah.

Mark: And then, but did you two know each other before then? Did you come to know each other because of that poem?

Endre: I knew Harry because we had been to some gatherings before and I was very impressed by Harry’s writing and about his presence. So, I guess these are kind of these things you don’t know really why you reach out to someone in the world. But for me, it was Harry and it felt almost destined to be that because I don’t know. Harry was, in my opinion, one of the really great young poets in Europe. And Harry is very different from me. Where I am kind of, like, a very emotional, a little bit without limits, but Harry is very different. So, we kind of have kind of different way of perception and way to work.

But the main reason why I reached out to Harry is that, in Norway, this tragedy has kind of, like, it sucked all the air out of the room, it’s everywhere. And when my publisher asked me to write the book about this, I needed someone from the outside, someone who could kind of see this tragedy also from a different point of view than I do as a Norwegian. So, there are many reasons why I reached out to Harry.

And I think this whole process of doing a book together, I never thought it would possible to share a book with someone because you have your own voice. But this has really changed that perception for me because Harry was… We needed to be two voices to be able to write through this darkness because this is an extremely direct and brutal book in some way. And it’s also a book that tries to bring some hope to this tragedy. I don’t know if we succeed in that, but there are so many things to talk about. I’m just going to leave it at there because I usually speak a lot more than I should, so I’ll just wait.

Mark: Can I come in and build on that really? Because, on the one hand, I think this is beautifully written. There’s a lot of skill and a lot of heart in this book. But it just strikes me to take this on must have required so much courage. I remember reading about this and seeing when it happened. I mean, was there not a part of you that thought, ‘Well, hang on, I’m going to leave that for other people.’ But what was it that made both of you think, ‘I want to take this project on?’

Endre: I think the ‘Prosjektil’ poem was kind of it came from… During the trial, I was home. I was ill, so I was staying at home and I was watching this trial. So, this ‘Prosjektil’ poem came from just kind of… It was a found poem that I heard on the screen and I wrote it down. And then I didn’t want to really write about this tragedy. But my publisher asked me, ‘Is there any possibility to write this book?’

I think braveness is one thing. For me, it’s basically the problem or the question of: how can you move so closely to other people’s tragedies as kind of an outsider? My father was a psychiatrist who helped some of the survivors after. I’ve talked with a lot of the survivors. But is poetry… In Norway, poetry has been very closely linked with personal loss and personal tragedy.

So, one of the most difficult questions is, how can you take an event that still affects so many people, like, parents, survivors, friends. It’s not a hundred years ago. It’s close, a few years since this happened. How can you kind of process that material in an artistic way as an outsider? Is that possible? I think it is because I think if poetry is only linked with personal loss, if you’re not able to write something about a collective trauma and make it into poetry, I think poetry has lost some dimensions. But so that’s a lot of difficult questions, ethical questions as well.

Mark: Harry, how was all of that for you?

Harry: I think part of, for me, reading about…the reading poetry responses to the tragedy, and sort of watching things like the Netflix 22 July, Paul Greengrass film and countless documentaries and at the same time reading through endless court documents, there was just a huge comparison between the pathologizing of the individual responsible and centring the focus on the tragedy and what happened and the survivors and the families and the bereaved and that process of recovery and survival that is ongoing. It’s something which doesn’t have an endpoint. It’s something that people must live with.

And it is extraordinary, the bravery of people who continue to go through that process. And there have been so many studies that have followed up on survivors and how they feel and how that impact of PTSD, how that’s impacted their lives, how it’s difficult to hold down a job, how you’ve got to sort of continually be in a position of self-care and self-awareness.

When I first met Endre to start working on this project, Endre, I think, had written four books of poetry at that point, have been a festival director for a major literary festival in Norway. And I, meanwhile, had been writing in my attic, and my first pamphlet had just come out. So, the sort of scale was really different. Endre was much, much more experienced as a poet than I was. And I was used to writing about scientific experiments and endangered species were the two big things that I’d been working on. So, to suddenly write elegy on this kind of scale was something completely new to me. But reading countless court documents and reading about survivors and their journey and the bereaved and their journey, I just found that it was impossible not to write about. And it felt that it should be part of our vocabulary.

Being geographical neighbours in the UK to Norway we’re so close to that country, and how can we know so little at the same time? So, it seemed extremely important to write about as a subject, and simultaneously completely impossible to write about.

Endre said that it was about picking up on the atmosphere and the sounds in the atmosphere, that everything would be chaotic. When we first started working on the poems, what we had to work with were small fragments. And coming from that into a position of then finding forms, finding the right form was really integral to carry that across. And we spent so long crafting carefully into these, as Endre says, these shadows, these shadow face shapes. And that point that felt where the poem itself it sort of gathered meaning and it started to find its form and it started… And each voice in each of the experiences that we’ve been reading through, which were so profound and intense, we were able to then collect together.

And in this particular poem, we’ve been reading about so many people who had been singing around the fire. A lot of the kids who go to Utøya, alcohol is banned, after the events of the day are over, the disco is finished, you dissolve back into the campsite and play songs around the fire.

And a lot of teenagers have been talking about the fact they’ve been playing songs by Datarock who are a quite famous Norwegian band, a bit like The Go! Team and playing Datarock and have been playing Michael Jackson and Cyndi Lauper as well around the fire. And it seemed it felt impossible not to write a poem that would be about that sharing of song, and at the same time the fact that that song seems to sort of continue on.

And for me, the symbol of the guitar is something which is, in any teenager’s life, it’s probably the one object that collects the least amount of dust. It’s the thing that we’re sort of addicted to. And I think a lot of people have had that experience of being in a garage band or being in bands with their friends or going along to gigs where their friends have been playing. And that felt extremely familiar across both countries.

In writing the poems. I’m conscious of the fact that they’re going to be translated into Norwegian, which is it gives you less of an opportunity to use idiom and wordplay. You’re really trying to think about: how is something going to transform into another language and still be extremely clear and mutually understood? And that was also very important here, which is partly how it ends up with this kind of clear style at the end of it.

Mark: It really is. And you pick up on, not just this poem but so many of them, you pick up on a really telling detail. You know, the guitar ‘newly sewn with a spider’s web’. I mean, it just says so much, doesn’t it? That no one’s been playing this for a while.

Last month I was reading Wilfred Owen’s war poem, ‘Futility’, and one thing I noticed when I recorded it is it’s a really well-known war poem. But I realized, you know what? If you didn’t know this was by Wilfred Owen, you wouldn’t necessarily pick up it was a war poem because it’s just quite a gentle poem, looking at this dead body and the feelings that come out of that. And similarly, with this, I think the context is one of the things that makes this a heartbreaking poem, that you’re reading it within the context of that sequence and we know what’s happened and we know what the absence is. So, it really doesn’t have to work too hard, does it?

Endre: I think it’s a fabulous poem in many ways because by picking this up now, I can see some qualities with it that I’ve been thinking about. I think some part of this project is that since the tragedy on the 22nd of July, there has been written numerous books, prose books. You know, Åsne Seierstad has written a brilliant famous book called One of Us. So, there’s so many tales that kind of are narratives of this event.

And I think if there’s one thing poetry can do, and it has not been written a lot of poetry about, there’s just some, is that you can go into a situation, you can go into this kind of chaotic moment that I think after hearing and reading about a lot of the survivors is that this feeling of chaos and fright. So, I think poetry can do something in describing going into kind of this tragedy. It’s in a different way than a prose book can.

Mark: So, as I understand it, some of the poems started with you, Harry, writing in English and some started with you, Endre, writing in Norwegian and then you swapped over and translated. Is that right?

Endre: Yes, that is right. At the same time, it must be said that they are co-written. They’re co-written because the nature of the project is that if Harry started the poem and I started the poem, it’s kind of grown together in a way. So, it’s not just so mechanically that I’ve written a poem and Harry has translated, and the opposite. These poems have kind of grown into each other. So, I think it’s impossible to kind of disconnect them in that way because… So, it’s co-written.

Harry: Yeah, as we went through the translation process, I would make alterations in the English according to Endre’s translations and vice versa. So, there was the conversation between the poems and how we approached them. And that went through right from the beginning all the way through to sort of the finished edit.

So, yeah, as Endre says, there was definitely while we kind of had written and translated first drafts effectively, as it developed, it became more and more of a conversation. We’d also said there were certain themes that we want to try and pick up on between poems. So, we’d sort of set ourselves that deliberate conversation from one poem to the next. So, this poem actually picks up on themes elsewhere in the book.

Mark: And can I pick up on the form? So, if you’re listening to this and you haven’t seen the poem, then I would really encourage you to go… Well, obviously, pick up the book, but if you don’t have it handy, then go to amouthfulofair.fm and look for this episode in the archive and you can see that the words of the poem are laid out in the shape of a shadow portrait. Like we say, it makes a face.

And I think this is the first time we’ve had a concrete poem like this on the podcast. So, I’m curious, given that you decided you were going to accept this heroic commission, if you like, and tackle this subject, what made you home in on this particular form as a way of doing it?

Harry: I think we had gone through a series of different forms that we tried out. I travelled across to Oslo, and Endre came over to here, to the UK, and we discussed different approaches that might work. I mean, for me, there were various things that… There was one thing, in particular, which was for my previous book, Finders Keepers, I had written a poem in the shape of the UK, and I’d established how to create concrete poems that were in a specific shape. And in that process, I’d also investigated concrete poetry for its properties of memorial, which was, with Finders Keepers, that particular book was about memorializing lost species that pretty much, by the time the book was published, would be vanishing from Britain’s wildlife.

And for this book, I looked at crafting the poems in a similar fashion, because there are various aspects to the concrete poem. One is that, again, thinking about the translatability from one language into another and how much easier that becomes when you’ve got an anchor point like a visual image. But also the other element, which is the fact that concrete poetry, as the De Campos Brothers described it, was to say it should be as easy to understand as a sign that points to the airport. It should have this quality to it. So, the concrete poem has that property. And in addition, looking back through quite a few poets when they first encountered concrete poetry, come at it via George Herbert’s ‘Easter Wings’,…

Mark: Yes.

Harry: … which is this poem which is all about death and resurrection. And peeking behind the curtain of that poem, in fact, is Simmias of Rhodes. Herbert was reading translations of Simmias of Rhodes, who himself was writing visual poems in the shape of an axe and an egg, and various other shapes that were found in the books that George Herbert had to hand.

Harry: So, Simmias of Rhodes was a poet who was around in 300 BCE or thereabouts and wrote poems in a variety of different shapes using what were known as technopaegnia technique, which means it’s literally a technical game, a technopaegnia, ‘paegnia’ being game.

And those poems, in and of themselves, the original technopaegnia that he was writing, were about this idea of conferring the transcendent onto the reader. And one of the ways it did that is that with the axe, in particular, it was about the axe that had chopped the wood to make the wooden horse that travelled through the walls of Troy.

And the idea was that this was, therefore, an object that had managed to make it beyond human life through something which had being instructed by the gods and into another life, into another immortality, in other words. And the argument of the poem is that you’re reading this poem now, and therefore, that idea, and if it’s an idea, then it’s in your mind. And if it’s in your mind, then it’s part of you has travelled beyond this world into an immortal realm. And there’s this idea that, as you read a concrete poem, part of you is traveling into this other space, into this beyond after space.

And so that felt, to me, to be the right form to use to talk about that place. And for me, personally, I don’t really believe in an afterlife, but I do also see that, particularly in Sami religion, there’s this view that all objects in the world have a soul. There’s a kind of animism to all things and both a kind of humanist perspective and a Sami perspective meet in the idea that there is a soul in all things, that all things are regenerating and are in a larger cycle of life. And so the two very much so connect. So, that was all part of why we had chosen that form.

Endre: I think, for me, when Harry suggested that, with this idea, when you go into the Memorial Centre under the government quarter in Oslo, there is a room where you find all the portraits of the people who died in this tragedy, all the 77 victims. This room is extremely… Yeah, you can imagine going into that room and looking into all these faces. And, for me, it’s very extreme, but at the same time, I thought, ‘This tragedy meets us through the perpetrator so much.’ And I thought, to give each poem the face or the shadow of a victim, it does something to you. When we read poetry, it’s abstract, it’s everything, but just the fact that these faces are meeting you as a poem does something to the way you read the book.

Harry: Definitely. Definitely. I think it’s very much so an extension of that grammar of memorial, isn’t it, with that room. That was incredibly moving, the 22nd of July Centre in Oslo.

Endre: When that is said, I teach at the Høyskolen in Kristiania, which is for text writers in Oslo. And then one of my students there was one of the survivors of Utøya, which was an incredible story that he told, very touching. But when I talked to him, it was about how do you balance that, showing faces of victims as words, biographical material? Where does the line go? What can you do?

So, this was also a huge discussion, the ethics about how do we present these kinds of faces of victims as poetry. Do we put biographical material inside the poem or do we not? We ended up after advice to shade that out so that there’s no specific biographical material connected to the individual faces, which was one of the advices we got. And we changed that.

Mark: One question I had was, there was an in a quote from Wilfred Owen I was reading in last month’s podcast was, he’s talking about war poetry. He said, ‘It can’t console. A poet can only warn.’ And I wondered what were your hopes, what were your intentions for a book like this?

Endre: I think this book has split… I think there’s different reactions to it. I think some people find it very provoking and very unnecessary. I think some people find it very difficult, and hard, and brutal, and I think some people find a lot of consolidation in these poems.

So, I think really, from the start, when we knew we had took this on, we knew there was not going to be one type of reaction. I think, in Norway, this is a difficult book to digest, if I’m not using the wrong expression, because it’s so close to us, it’s everywhere, and the book itself doesn’t give any explanation. It’s moving into the dark, fear, and chaos room of what happened.

So, I think the basic thing to be a little bit cliched is that you want people to ask a question. When you read this book, I hope that creates some question, good or bad, to the reader. And the reception in Norway has been very different from the reception in England, which shows these things are very touchy still, of course, in Norway. So, for me, to have had readings outside of Norwegians’ has been very useful, I’m very glad for that because this dark, cold matter is still such an integral part of Norwegian society now.

Harry: If you look at something like The Poetry Pharmacy, there is definitely an attitude and a view that poetry is there can offer a kind of salve for mental health and has such an important role to play in mental health in showing to us that we are not alone in how extreme we might feel and grief is universally part of that contract of love. We love and so we grieve, and we grieve, so we love. And the fact that poetry can kind of speak back to that, I think, is intensely valuable. Poetry has this capacitive nature to both hold on to something important, and to electrify our own understanding, and to make something familiar glow in us. And I think that’s exciting.

When it’s talking about something which is a national tragedy, which is so painful, and raw, and difficult to address, the individual feelings that we have that we find typically inexpressible can sometimes find a sympathetic resonance in a poem that we’re reading. And that in of itself, that sudden moment of connection across time, is extremely powerful and part of the human condition that poetry can speak to.

And I think, as much as it was incredibly difficult and continues to be really difficult to talk about, and as Endre says, we had no aspirations that these poems would actually be able to console fully or to find any kind of answer, they can at least put an arm around the shoulder. And this is what the ambition of the project was, to say, ‘Hey, you’re not alone. Share with me.’ And that’s the kind of emotion that got the poems off the ground in the first place where we started from, and it’s also where we ended.

Mark: Thank you both. I really do think this is a poem that it grows the more you’ve… I mean, I’ve spent a bit of time with it before the recording today, and that’s been my experience is it’s really grown with familiarity. That’s sad, in a way, because of the depth of the emotion that’s sinking in. But I really think the two of you have done a wonderful job with this book. So, let’s take a listen to the poem again, both versions. Thank you very much.

Harry: Thank you, Mark. Thanks for having us.

Endre: Thank you so much for having us, it’s an honour.

‘As I push the door’

by Harry Man and Endre Ruset

As I push the

door, the hollow of your

guitar, newly sewn with a spi

der’s web chimes a brok

en chord. Some day

the Sun will absorb

the Ear th. Grief,

like music, p ossesses

us. I run

a finger

over the

surfaces

both of us

have to

uched; your

heights on

the door,

the neck of

your guitar,

your songs

in this room

now rest

as snow

at the window.

Norwegian version

Når jeg åpner

døra, klinger hulrommet

i gitaren din, nylig sydd med spi

ndelvev, fra en ødelagt

streng. En dag vil

sola slu ke jorda.

Musikk holder

tak i oss. Jeg stryker

en finger

o ver ov

erflaten

begge av oss

har ber

ørt, høy

den din

på døra,

gitarhalsen

din, sangene

di ne hviler i

dette rommet

som snø ved

vinduet.

© Harry Man and Endre Ruset 2023

Utøya Therafter

‘As I push the door’ is from Utøya Therafter by Harry Man and Endre Ruset, published by Hercules Editions.

Available from:

Utøya Therafter is available from:

The publisher: Hercules Editions

The Norwegian edition, Deretter, is available from:

The publisher: Flamme Forlag

Harry Man

Harry Man has won the Stephen Spender Prize and a Northern Writers Award. Additionally, he is the recipient of the UNESCO Bridges of Struga Award. With Endre Ruset, he co-wrote Deretter (‘Thereafter’) which was published by Flamme Forlag in Norway and in pamphlet form by Hercules Editions in the UK. It was a Dagblaget Book of the Year 2021. He has been a Clarissa Luard Award Wordsworth Trust Poet in Residence and teaches Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. You can find more of his work at www.manmadebooks.co.uk

Endre Ruset

Endre Ruset is a poet, literary critic and translator and teaches regularly in schools and universities across Norway. He has been awarded a Bjørnson Scholarship (2005) and the prestigious Bookkeeper Scholarship (2015). He was also shortlisted for the Bastian Award for Translation. His collection Noriaki was re-released as a jazz album in collaboration with renowned Norwegian jazz musicians Jon Balke and Stian Omenås.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith

Episode 70 Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith Matthew Buckley Smith reads ‘Drinking Ode’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: MidlifeAvailable from: Midlife is available from: The publisher: Measure Press Amazon: UK | US...

The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden

Episode 69 The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John DrydenMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage about the Great Fire of London from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.Poet John DrydenReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Great Fire of London,...

0 Comments