Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 57

Bede’s Sparrow by Isobel Dixon

Isobel Dixon reads Bede’s Sparrow and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.

This poem is from:

A Whistling of Birds

Available from:

A Whistling of Birds is available from:

The publisher: Nine Arches Press

Bookshop.org: UK

Bede’s Sparrow

by Isobel Dixon

A sparrow flits through the hall,

its hubbub of feasting men,

the meaty, fuggy, smoke of them.

A spell of warmth and hearth,

post to post, high perch,

a crossbeam bird’s-eye view –

head cocked to reckon it,

the mead-hall din below.

Jocular glut, jostling stories,

battle-talk and rut; crumbs

among the rushes, toppled cup,

the hanging cauldron’s heat.

Mark the sparrow’s pause, now

the slanting rain it tumbled from

has ceased to beat. This quieting –

breath upon a pipe, the click

of deer-horn dice. Sky-sough,

a sigh of flakes upon the thatch.

Hound-yawn, haunch-twitch

in the fire’s glow. A fan of feathers,

wing-flex, flight: bird-blink,

up and out into the night,

the mystery and purity of snow.

Copyright © 2022 Isobel Dixon. First published in New Statesman in 2022 and the collection A Whistling of Birds (Nine Arches Press, 2023 ). Reprinted by permission of the author.

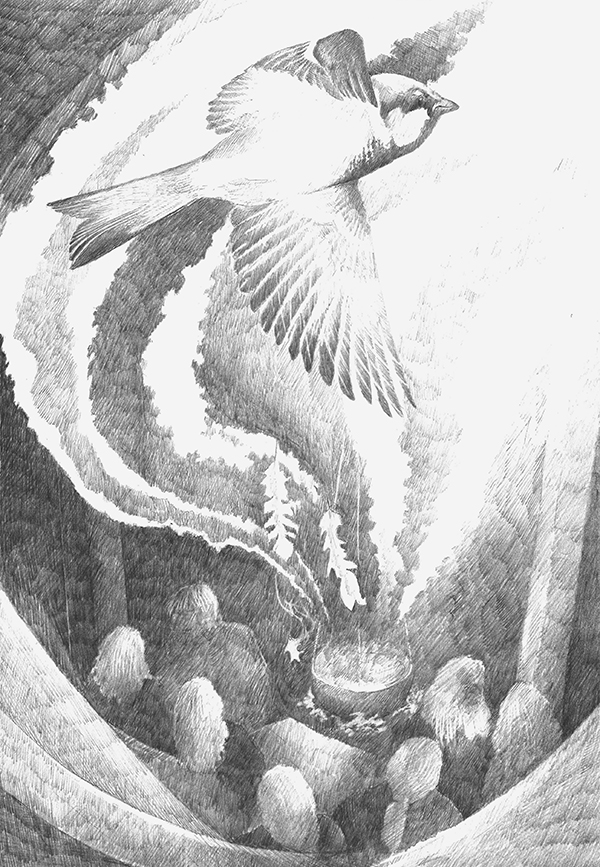

Illustration by Douglas Robertson

Interview transcript

Mark: Isobel, where did this poem come from?

Isobel: Where did this poem come from? I guess it came from the birds and from the Venerable Bede. It came from my study, surrounded by books and my head and the computer during the spring of 2021, during the lockdown times. And it came also from echoes of my father’s study back in South Africa, and his book of The Ecclesiastical History of the English People by the Anglo-Saxon scholar and monk, the Venerable Bede.

My father was a science teacher from Scotland but also ordained as a minister. And he went to South Africa, both to teach and to dean of… he became, eventually, dean of the cathedral in Umtata on the east coast of South Africa. And he was fascinated by the history of the missions, the mission stations. And for years, I looked at the spine of the book by the Venerable Bede, and I didn’t really know anything more than that he was a scholar and a monk.

I came back to the Venerable Bede via D. H. Lawrence. And D. H. Lawrence has been a complex fascination for me for a long time. I came to Lawrence first via his poetry, the wonderful poem, ‘Snake,’ his poem about bats, and as I wrote my own poems, largely, in the beginning, really about nature and love, but always throughout all my writing, I write about nature. I learned more about other things that Lawrence had written. But it was only during lockdown that I read The Rainbow. And I was fascinated by how much nature there is in his prose as well, something I’ve never noticed before, how beautiful his nature descriptions are. And The Rainbow ends with a scene in which he quotes the simile of the sparrow by the Venerable Bede, which is the scene that I’ve recreated in ‘Bede’s Sparrow’.

You have a hall full of men in medieval times, which for me felt a bit like a scene from Gawain and the Green Knight I’d studied in my first year at university: there’s a very medieval feasting scene, snow falling outside, and the sparrow flying in through one door, pausing a while, and then flying out the other, which is meant to speak to the transitoriness of life, and a question of a search for spiritual significance. And it was just such a striking scene to me, which strangely, I only read via reading The Rainbow and then reading a scholarly essay from 1947, online on JSTOR, about The Rainbow and about the sparrow and the nature imagery. And then I just had to write my own version. It sometimes happens, I think, as a poet that something strikes you and you want to reinterpret it.

Mark: Yeah, it’s like you’re answering back or continuing the conversation. Yeah, you sent me scurrying to the internet because I remember the end of The Rainbow, I remember the horses, but I’d completely forgotten about the sparrow. So I went back.

Isobel: Yeah, did you go back?

Mark: I went back and had a look and there it is. Yeah, indeed it is and it’s such an amazing, unforgettable…well, I forgot it! [Laughter] I forgot it was in The Rainbow but I did remember it from Anglo-Saxon studies, just that image of life that is just like passing through the mead hall, and we don’t know what’s before or after. It’s really extraordinary. And you captured it absolutely beautifully in this poem. And your sparrow has migrated a long way, hasn’t it? From Scotland to South Africa and back.

Isobel: Yes, but the sparrow is everywhere, fewer sparrows here, of course, than there used to be, which is sad. I think sparrows were much more numerous. They would have literally been large flocks of them at times, we don’t see here, I think. When I’ve been to Italy, where D. H. Lawrence, of course, spent time as well, I see many more sparrows hopping around than I’ve seen here.

You couldn’t possibly remember all the nature comparisons and metaphors that he uses. So that scene where Ursula walks through the forest, and she goes into the forest and out the other side, before the horses, which he compares to the sparrow going in and out of the hall, that sort of transitory time. It’s also about rebirth. You know, it’s about entering a new space. It’s like a kind of renaissance in a way.

Mark: Okay. But what prompted you to write about the sparrow? You remembered it, but how did you know this was going to be a poem?

Isobel: While I was at my desk, it was a miserable grey time for all of us. I think there was that sense of, ‘Where is this going?’

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: You know, the meaning of our lives, really big existential questions. And I was aware of time passing, being separated from people I loved in South Africa, or separated from people I loved all over the world, and it just spoke very, very clearly to me. I also saw an archaeological site, a simulation of what it would look like for the sparrow to fly through a mead hall like that.

Mark: Really.

Isobel: I’ll send you the link.

Mark: Oh, yes. I’ll put it in the show notes, folks.

Isobel: Yes, I can send you the notes for that. And the essays from 1949 actually, it was E. L. Nicholes’ essay, ‘The “Simile of The Sparrow” in The Rainbow by D. H. Lawrence’.

Then I was scurrying around the internet, one thing leading to another and imagining that Beowulf-like banqueting scene, the idea of the soul’s journey. And in the E. L. Nicholes’ essay, Nicholes mentioned a William Wordsworth poem. And that was also retelling the story of the sparrow. So this is quite spooky. So because I was alerted, in Nicholes’ essay, to the mention in The Rainbow, I was intrigued by Lawrence talking about it. I then went to the Wordsworth sonnet, and it’s called ‘Persuasion,’ and it’s in his Ecclesiastical Sonnets.

Mark: Great. I will link this one as well.

Isobel: Link to this one. But then there’s another excellent blog where…I think it’s somebody called…well, the blog is called ‘First Known When Lost.’ So the blog is called ‘First Known When Lost,’ and an entry from 2015 was headed, ‘A Sparrow, A Fluttering Thing.’ It quoted the William Wordsworth ‘Persuasion’ but then I learned about a further poem by an American poet called Stephen Dobyns, called ‘Where We Are’ exactly written around this image. Now, I had already finished my poem by this stage.

Mark: Okay.

Isobel: And so when I got to the Dobyns poem, I felt suddenly, ‘Oh, no, this is a much longer poem, and he’s done exactly what I’ve done, but he did it before me!’ So when I got to the Stephen Dobyns poem, I had already finished my ‘Bede’s Sparrow’ certainly in a long first draft and then just tinkered with the form. So I would say at first a little bit put out, as poets are when we find we aren’t the first to tread this ground! But then this actually happens a lot in all kinds of writing that the same themes inspire us, and I actually love the way that the poems can be little time-traveling capsules between poets and between writers of different forms.

I really, really found it incredibly spooky, sitting there alone, isolated during lockdown and this sparrow was flying between the beams of the mead hall, but between centuries between Wordsworth and Lawrence, Stephen Dobyns, myself, between the blogger, and I just felt really touched by kind of magic really.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: So for me, this poem has a magical feel. Because it came as if by magic, I wrote it really fast. But it’s the coalescing of so many different things, and so many writers’ thoughts, all the way back to the Venerable Bede telling this story, writing it down.

Mark: What a lovely thought and a lovely image for poetry. You know, that’s really how it happens. It gets handed down, or in this case, it flies from mead hall to mead hall, from poet to poet.

Isobel: Yeah. And in different forms.

Mark: Yeah. And it’s always fresh.

Isobel: Everyone chooses a form.

Mark: Yeah. So I will link to all of those so that readers can follow the trail. I guess another way of thinking about it is lineage, that it’s gone from Bede to Wordsworth, to Lawrence, and through to contemporary poets like you and Stephen Dobyns.

Isobel: I’m sure there’s more out there. I’m sure that when you do your podcast, you’re going to attract a few more birds flying across saying, ‘Well, I’ve got one.’

Mark: Well, maybe people could leave a comment. Leave a comment on the blog, let us know and we will see if we can map the sparrow’s flight. Okay, so you had your sparrow visit. How did the poem evolve? How did it start and how did it find the form it’s in now?

Isobel: So the poem started, for me, with the lines, the first three lines. The sparrow flits through the hall, ‘its hubbub of feasting men, / the meaty, fuggy smoke of them.’ So those words formed when I was thinking about the flight of the sparrow and seeing that simulation as well. And it is a very strange thing, isn’t it? Why we need to write things down in our own words, how we need to retell something, even if it’s just telling it to yourself, I just felt a real impulse to shape this for myself and think it through. It’s a way of thinking things through, about thinking deeply about things is writing for me. And I wanted to sort of hear the rain outside, the noise down below, but the quiet for the bird above. I wanted to imagine that the dogs, the hounds, the ‘Hound-yawn, haunch-twitch / in the fire’s glow.’ That moment, that cinematic moment really, there’s something very, very visual and cinematic even about the original.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: When I first wrote it, it just ran on, all in one block of text. It’s quite a narrow block of text on the page running down. But then I realized that it needed more space, that it needed more breath for the reader. I like to think of how the reader reads it on the page or how it’s heard, spoken as well. Like, when I write I always speak to myself, speak the lines.

Mark: Really? And I think we can hear that when you read it. You could really hear all the rhythms and the stops and starts. And it’s really intriguing to hear that that’s part of your process because I know some poets don’t do that. I remember hearing Simon Armitage talking about his translation of Gawain and the Green Knight and he said, when he recorded it for the audiobook or TV, he said, that was the first time he’d ever spoken it aloud. And I thought, ‘Really? And you managed all of that?’

Isobel: Yeah, that’s extraordinary to me. Sometimes the spoken, in my head, words come first. I find I have the ideas for lines that come upon me when I’m running or walking, swimming.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: In the bath or washing dishes. There’s something about motion and water.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: Trains and planes are marvellous, too. A train is preferable, of course. But motion is so important. And that motion and that rhythm of the movement for me comes into the words. Also as a child, I had a really, really terrible stammer. And I was very fortunate to have had an enlightened headmistress of our school who was very concerned with remedial work for speech and for reading. I had time away from classes when everyone else went to what we called PT, what you call PE. And in those days, we had to do needlework. I skipped those to have my speech lessons. I can’t say it today and that was really helpful.

Mark: And do you think that’s helpful to you as a poet that you had such a focus on speech from such an early age?

Isobel: I mean, this is a whole different conversation really. But there are a lot of poets with stammers. And a lot of poets you wouldn’t know had stammers and work around their stammers. But if you’ve stammered, you do recognize certain breathing patterns and ways of compensating. And I’ve had this conversation with several published poets around stammering, and there are poets who’ve written openly about stammering, so I’d like to do a program about that sometime. But I think people who stammer – there is often a real interest in words, and there’s a fascination with words. And I think I sometimes, wittingly or unwittingly, set myself quite difficult sequences of things to say. In the poems it’s like, let’s stretch the language. Let’s make it as acrobatic or interesting as possible.

Mark: ‘Acrobatic’ is a really great word, I think, to describe what you do throughout the collection. It’s incredibly rich, and agile, and at times exuberant, the way that poems leap around the page. I mean, in this one, you’ve got, you know, right from the beginning the ‘hubbub of feasting men, / the meaty, fuggy smoke of them.’ I mean, that’s the whole of the Beowulf feasting scenes in two lines, isn’t it? It’s just, you really want to be there. I mean, vegetarians turn away now, but all the meat and the smoke and the, you know, it’s that kind of cosiness of being inside when all the elements are out there. And all the way through this poem, you’ve got alliteration, you’ve got assonance, you’ve got internal rhyme, half rhyme, the language is really knitted together.

Isobel: Thank you.

Mark: I’m not surprised it maybe takes a bit of careful consideration about how you put all those sounds together, and with a view to reading them aloud.

Isobel: Thank you. It’s so kind of you to say all those things. I don’t think, though, I could write a poem, and ever share it before I had read it aloud – and read it aloud along the way, and read it aloud as a whole – because sometimes the rhythm of one stanza might conflict with the rhythm of another. And in the course of reading it aloud and hearing it several times over, I sandpaper things differently and switch words around. And it’s an absolute joy to do that. I love the craftsmanship of it. I love that space, where you get to get lost in the poem.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: In the making of it.

Mark: Yes. Yeah.

Isobel: Beautiful concentration, it’s where I’m happiest. So it was lovely in the middle of that really gloomy spring of 2021, compared to the beautiful golden spring that we went into at the beginning of lockdown – which was this extraordinary contrast, you know, we were thinking it wouldn’t last very long. You know, ‘maybe in a month or so we could go back to our lives. But in the meantime, let’s enjoy the sunshine and pray for those we love and care about elsewhere. But what else can we do? We’re here.’ But by the time April 2021 came along, when I wrote this, we were all exhausted.

And it really did feel to me like the sparrow was a magical moment of visitation by this bird, via the lineage that you speak of. And also in conversation with other bird poems in my collection, in what was becoming the final version of A Whistling of Birds. In A Whistling of Birds, there’s a robin that sings, in Woburn Place, which is where W. B. Yeats lived. So Yeats is not mentioned in that poem, but Yeats is there, as though he’s listening in a different era from his window. There are herons, era, egrets, there are hummingbirds. And I know you’ve done a podcast on D. H. Lawrence’s ‘Humming Bird’.

Mark: That’s right.

Isobel: So Lawrence is very important to the genesis of A Whistling of Birds. But he is not the only presiding spirit. There are voices from so many other artists, musicians and writers in the book, Georgia O’Keeffe features in a poem called ‘Everywhere Apricots’ from Santa Fe, which I visited in order to go to a conference about D. H. Lawrence, but also loved the fact that Georgia O’Keeffe, who inspired me so much as a young girl had also lived in New Mexico.

And there are conversations with other poets who loved nature. In fact, there’s a three-part poem, which was originally three separate short poems, and then I saw that really they belonged together in one, and the poem as a whole is called ‘Conversations.’ But the three parts are called ‘Hawkweed Burning,’ which is really for Elizabeth Bishop, directed to her and thanking her for her inspiration as such a clear-eyed nature writer as someone who paid superbly close attention to the creatures. And then ‘Our Doubtful Art’ brings in John Berryman, Glenn Gould, and Emily Dickinson.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: Dickinson and Berryman, of course, also writing wonderfully about nature as well. And then ‘Dear Engraver,’ the final one is for William Blake really. He is the dear engraver of the title.

Mark: So there are lots of poets on your poetic family tree. And Ted Hughes is in there too, isn’t he?

Isobel: Yes, that’s the poem called ‘Dead Heron, Burnt Fox.’

Mark: That’s right. Yeah.

Isobel: And that’s both the Irish artist Barrie Cooke and Ted Hughes and his ‘Thought Fox.’ ‘Thought Fox’ is a much gentler version, really, of the dream he had of a burnt and mutilated fox saying that he was killing them and he must stop.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: And the very next day, he stopped his English literature studies, left the English Lit course, and went on to I think, is it anthropology?

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: Because he felt that the study of English literature was working against his creative instincts.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: And Barrie Cooke was looking at the idea of a heron that had been given to him, a dead heron, to paint. But his domestic duties were keeping him from painting the heron before it had begun to rot. And so both those images came together for me, two different parts of two artists saying, ‘Focus on the art. Focus on the art, don’t let the art escape you.’

Mark: Yeah. And Hughes was famously influenced by D. H. Lawrence in his animal and nature poems. And Lawrence went to more exotic places, or exotic for us in England, and wrote about creatures as far aboard as Australia and South America.

Isobel: Central America, Mexico, and New Mexico in America.

Mark: Okay, and then Hughes wrote a lot about English birds and beasts and fauna, I guess you’ve got access to both of those in your collection, haven’t you? You’ve got all kinds of critters.

Isobel: Yeah, Hughes was a very strong influence as well in my teenage years and at university. Seamus Heaney, Hughes, Gerard Manley Hopkins also beautiful nature poetry, of course. And to return to the question of stammering, ‘Glory be to God for dappled things’. It’s also a tongue-twister of a poem.

Mark: Huh, yes. And coming back to the form of ‘Bede’s Sparrow’, so you’ve ended up with these lovely three-line verses. And you were saying it was cinematic just now. Like for me, I experienced the hop from each one verse to the other a bit like the shift in the shot. You know, one minute we glimpse the warriors feasting down below and then we get ‘the crossbeam bird’s eye view’, ‘head-cocked to reckon it, the mead hall din below’. It’s like going from shot to shot. I don’t know if that’s what you were intending, but that’s how it comes across for me as a reader.

Isobel: I love that, I really do. And for me also, I saw those narrow triple lines, the short stanzas, as a bit like the crossbeams themselves of a long narrow hall.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: Not that it’s in any way a concrete poem, and you don’t need to know the form to hear it. But all of those things come together in a very organic way for me, and I often change the initial form to something different. Some poems might come fully formed very quickly. There’s a very short poem called ‘In Nature’ in the collection and that needed for me to be balanced as a centred poem, a little short, centred poem.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: And some of the poems are, as you said… you used the word ‘agile’, and…

Mark: Yes.

Isobel: …they’re sort of exploded or flying across the page. And that’s because of the subject matter, somehow it suits it. And you can’t really explain why and maybe it doesn’t matter to anyone else but me. But in the same way, that a carpenter might carve a little secret symbol, a mouse under the table. I think every poet has their own pleasures that they get from how they arrange what they do.

Mark: Yeah, absolutely. And, folks, if you read the book, there’s a wonderful variety of different forms, like, it’s the bats and the bees, they’re flitting all over the page, aren’t they? And then the whale is luxuriating and…

Isobel: Sinking to the bottom of the ocean really.

Mark: Yeah. It’s pretty amazing.

Isobel: I suppose, in terms of the form of the poems and what people see, I would love to mention that the collection, A Whistling of Birds, began as a collaboration with Scottish artist Douglas Robertson. And he has twelve very beautiful images in the book, including the cover image of Arctic terns flying across the cover. And there’s a beautiful image of Bede’s Sparrow. Very, very detailed, a pencil-stroke-upon-pencil-stroke image of that bird’s eye view looking down. So I was thrilled when he did that.

We don’t ever do anything prescriptive. We’ve worked back and forth for more than a dozen years now on some of these poems, and it all began with the poem about the whale, but it’s wonderful when he might do a drawing, as he drew the Arctic terns, and then I wrote a poem, a very short poem in flight to answer the Arctic terns about their circumnavigation from pole to pole.

Mark: Yeah.

Isobel: But then with ‘Bede’s Sparrow,’ I sent him ‘Bede’s Sparrow,’ and he was like, ‘Ah, I know exactly what I’ll do with that.’ And he did the drawing.

Mark: Wonderful. And again, the interplay between the poems and the illustrations really opens up another dimension to the book. And I mean, we were saying earlier on, there was one line in another poem that stood out to me where you said, ‘So after all, there is wonder still’. And I think in the poems and the illustrations, this is really a book of wonder. And it’s very heartening to read that because we’re in a little bit of a cynical, ironic age, where a lot of time poets are, I don’t know, maybe a little scared to go near wonder and joy. But you do that just beautifully in this book. And it is a very heartening book to read for that reason.

Isobel: Thank you again. I guess, maybe sometimes it may seem careless or naïve when there’s so much threat to nature, and so much threat to human life, there’s a lot to despair about. But actually, despair isn’t really an option. I think we have to seek solutions to our environmental crisis, we have to seek ways to protect and rebuild the world we’re in.

And I firmly believe that we cannot repair things, if we don’t know what the wholeness and the beauty of the original of what is lost and what we’re losing is about – which is why advocates like David Attenborough are so important, showing how extraordinary the natural world is and how much there is to wonder at and be awe-struck by, but then also helping to sound the alarm and try to do what is needed to repair and to rescue.

There’s a line from William Blake, where he speaks of labouring well ‘the minute particulars’, it’s an injunction actually, ‘labour well the minute particulars’. And that’s what I want to do is by looking at the minute particulars to fulfil a duty to care for the planet. So the poem you refer to, about ‘there is wonder still,’ is a poem called ‘On First Spotting a Snake’s Head Fritillary,’ which is a beautiful, beautiful flower I’d never seen before, except in pictures by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. It’s a beautiful watercolour called ‘Fritillaria’, from Walberswick. I have a postcard up on my bookshelf behind me.

And I loved that plant before I saw it in the wild because of his drawing, because of the art, and I wanted to see it. But when I saw it, I really wanted to cry. I was so happy to see this beautiful, unusual cross-hatched flower in the rain down at Dartington. And that’s what I mean by the wonder. You’ve got to be open to the wonder and then fight to protect our wild spaces so that that wonder is not lost. So it doesn’t only exist on the page, but it exists in a living green world that we can live in and enjoy together.

Mark: Yeah. And you know, as you speak, the minute particulars I think is something that you’ve really done throughout the book. And this poem in particular, I think it’s the precariousness, that is key to the wonder, isn’t it? In Bede’s simile and the way you’ve expressed it, so maybe this would be a good point to listen to the poem again and savour those minute particulars. Thank you so much, Isobel.

Isobel: Thank you so much, Mark. It’s been wonderful speaking to you.

Bede’s Sparrow

by Isobel Dixon

A sparrow flits through the hall,

its hubbub of feasting men,

the meaty, fuggy, smoke of them.

A spell of warmth and hearth,

post to post, high perch,

a crossbeam bird’s-eye view –

head cocked to reckon it,

the mead-hall din below.

Jocular glut, jostling stories,

battle-talk and rut; crumbs

among the rushes, toppled cup,

the hanging cauldron’s heat.

Mark the sparrow’s pause, now

the slanting rain it tumbled from

has ceased to beat. This quieting –

breath upon a pipe, the click

of deer-horn dice. Sky-sough,

a sigh of flakes upon the thatch.

Hound-yawn, haunch-twitch

in the fire’s glow. A fan of feathers,

wing-flex, flight: bird-blink,

up and out into the night,

the mystery and purity of snow.

Copyright © 2022 Isobel Dixon. First published in New Statesman in 2022 and the collection A Whistling of Birds (Nine Arches Press, 2023 ). Reprinted by permission of the author.

A Whistling of Birds

‘Bede’s Sparrow’ is from A Whistling of Birds by Isobel Dixon, published by Nine Arches Press.

Available from:

A Whistling of Birds is available from:

The publisher: Nine Arches Press

Bookshop.org: UK

Isobel Dixon

Isobel Dixon grew up in South Africa, where her debut, Weather Eye, won the Olive Schreiner Prize. She studied in Edinburgh and now lives in Cambridge. Her fifth collection, A Whistling of Birds (with illustrations by Douglas Robertson), is published by Nine Arches Press, who have also published A Fold in the Map, The Tempest Prognosticator and Bearings. All of her collections are separately published in South Africa. She co-wrote and performed in the Titanic centenary show The Debris Field (with Simon Barraclough and Chris McCabe) and enjoys collaborating with writers, artists and composers. Her work is recorded for the Poetry Archive.

Photo: Jo Kearney

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Empathy by A. E. Stallings

Episode 74 Empathy by A. E. Stallings A. E. Stallings reads ‘Empathy’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: This Afterlife: Selected PoemsAvailable from: This Afterlife: Selected Poems is available from: The publisher: Carcanet Amazon:...

From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer

Episode 73 From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, by Emilia LanyerMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer.Poet Emilia LanyerReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessFrom Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Lines 745-768) By Emilia...

Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani

Episode 72 Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani Z. R. Ghani reads ‘Reddest Red’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: In the Name of RedAvailable from: In the Name of Red is available from: The publisher: The Emma Press Amazon: UK | US...

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

Many thanks to Isobel for sharing her captivating poem and the story behind it (now I have many other sparrow poems to look up!). I just wanted to drop by and say that I am another poet who was inspired by Bede. His sparrow makes an appearance in my “December poem,” to be published in Peauxdunque Review.