Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 24

Humming-bird by D. H. Lawrence

Mark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Humming-bird’ by D. H. Lawrence.

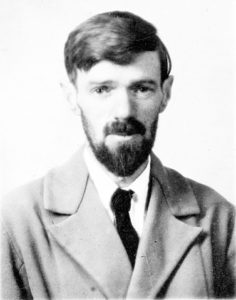

Poet

D. H. Lawrence

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

Humming-bird

by D. H. Lawrence

I can imagine, in some otherworld

Primeval-dumb, far back

In that most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed,

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

Before anything had a soul,

While life was a heave of Matter, half inanimate,

This little bit chipped off in brilliance

And went whizzing through the slow, vast, succulent stems.

I believe there were no flowers, then

In the world where the humming-bird flashed ahead of creation.

I believe he pierced the slow vegetable veins with his long beak.

Probably he was big

As mosses, and little lizards, they say, were once big.

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

We look at him through the wrong end of the long telescope of Time,

Luckily for us.

Podcast transcript

There’s something enchanting about hummingbirds, isn’t there?

I remember a few years ago, sitting my friend Peleg’s garden in Los Angeles, we were having breakfast and and Peleg said, ‘Oh look’, and there was a little hummingbird just hovering at the side of the table. Dipping its beak into a flower on one of his cacti.

And it was so tiny, and the way the wings looked as they were whirring away, it was like one of those little battery-powered fans that you you hold on a hot day to keep yourself cool. The wings looked like a miniature propeller, it looked so strange that it was hard to believe it was real, let alone natural.

And I think there’s maybe something about hummingbirds that attract poets and brings out the best in them. You might remember Shazia Quraishi in Episode 7, who read us an extract from her sequence The Taxidermist; the part she read was about performing taxidermy on a mouse, but the taxidermist in the sequence also works on hummingbirds and there’s a hummingbird on the pamphlet cover and some gorgeous hummingbird description inside.

Also Mona Arshi, who appeared in Episode 15, has a beautiful poem called ‘Hummingbird’, in her first collection, Small Hands. And Emily Dickinson, who I featured in Episode 18, has a hummingbird poem that describes the bird thus:

A route of evanescence

With a revolving wheel;

A resonance of emerald,

A rush of cochineal;

Isn’t that marvellous? So there’s obviously something poetic about hummingbirds. And today, D. H. Lawrence has given us a prime specimen.

Lawrence grew up in England but he travelled extensively as an adult, to places including the United States, Mexico, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Australia and southern Europe. And he was entranced by the weird and wonderful creatures that he saw on his travels, which must have been quite a shock in those days to go from England, which is pretty cold and clammy, where the wildlife consisted of a few soggy sheep and voles and badgers, to being in roasting landscapes full of snakes and mosquitos and kangaroos and mountain lions and eagles, and of course hummingbirds, all of which featured in his poetry collection Birds, Beasts and Flowers, published in 1923.

And this poem is full of Lawrence’s adventurous spirit; it doesn’t just feature an outlandish creature, it speculates on its origins way back in prehistory. You know, there aren’t all that many poems about prehistory, or indeed the far future in science fiction. I know as soon as I say this you’ll be able to think of quite a few counter-examples, but they’re not really the mainstream of poetry, are they? You know, novelists and particularly genre fiction writers, are more likely to do this kind of thing – futuristic fantasy, caveman chronicles, dinosaur safaris. So it’s quite refreshing to get a primeval poem like this.

But we need to be on our guard, as we can’t quite claim this as a natural history poem. Because, right from the start, Lawrence is brandishing his poetic licence. He is playing very fast and loose with the facts of biology and evolution. Listen to the first line again:

I can imagine, in some otherworld

Notice that he begins with, ‘I can imagine’ – he’s signalling right from the start, ‘This is a work of imagination. This isn’t necessarily the hummingbird as we know as we know it, the hummingbirds of biology, or even the ancestral hummingbirds of prehistory. This is the hummingbird that I can imagine, in some otherworld’.

And he keeps this up throughout the poem, reminding us that he’s making it all up; he begins the third verse with:

I believe there were no flowers then,

And of course we can imagine the evolutionary biologists tearing their hair out and saying, ‘It’s not a matter of whether you believe there were flowers or not, you need to look at the evidence!’. But of course Lawrence doesn’t need to, he’s got his poetic licence, his Get Out of Jail card, and he can do what he likes, because it’s his poem and his hummingbird and his ‘otherworld’. And he keeps going in this vein:

I believe he pierced the slow vegetable veins with his long beak.

Probably he was big

As mosses, and little lizards, they say were once big.

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

I mean, could he get more Cavalier with the facts? He’s blatantly making stuff up, inventing a whole new diet for the hummingbird to compensate for his whim in dispensing with flowers. And as if believing in things weren’t bad enough, he goes one further, and starts saying ‘probably’ this and ‘probably’ that. ‘Probably he was big’, is such a breathtakingly vast assumption, stated so casually.

And yet… maybe it’s not such an improbable leap after all. According to the scientists, there were all kinds of weird fauna back in the day. Apparently, once upon a time, there were giant rodents in South America, the size of bulls. Imagine that! It’s ridiculous and horrifying at the same time.

And as Lawrence writes, ‘little lizards, they say were once big’. They were indeed once big. In fact, there is a theory which I understand is quite respectable these days, that birds are evolved from dinosaurs. I don’t know if that theory was current at the time Lawrence was writing this. Or if it was current, whether Lawrence knew about it. But if not, isn’t it just delicious to think that Lawrence has made this big unscientific imaginative leap and somehow landed on the truth that hummingbirds and giant lizards and jabbing, terrifying monsters are connected in some way? Maybe there’s something in this poetry business after all.

And let’s just pause to savour that line:

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

It feels like that word ‘probably’ has no right to be there, asserting that the tiny hummingbird was this giant monster, without a shred of evidence. And it sounds so casual, so insouciant, like it’s idly discussing the weather, and then suddenly by the end of the sentence we’re being pinned to the wall by this ‘jabbing, terrifying monster’.

So I think that’s the first thing to establish about this poem, is that it is a work of fiction, a flight of fancy, I think is probably an appropriate metaphor to to use for it. And that makes it a really fun and delightful poem. And I must admit, I’m not the world’s biggest D. H. Lawrence fan. I generally enjoy his poetry. I read his novels years ago and I thought they were good, but he was never really a favourite author of mine. And I think one reason for that is he can be a bit earnest, a bit hectoring a bit preachy, whereas here he’s a bit more relaxed and not taking himself so seriously. And that tone continues right to the end:

We look at him through the wrong end of the long telescope of Time,

Luckily for us.

That’s quite a daring ending, isn’t it? Especially if you remember this was published in 1923, when poetry was generally considered to be something of a high-minded pursuit, so that it wasn’t really the thing to have humour in a serious poem. You know, there would be nonsense verse and light verse and children’s verse, that was supposed to be silly and diverting, but when it came to the real thing, the grown-up poetry with a capital P, it was generally delivered with a straight face.

And the year before, 1922, was of course the year of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, which is seen as a convention-shattering, epoch-defining work, but it’s fair to say that there aren’t many laughs in The Waste Land. Philip Larkin once said in an interview that the trouble with being funny in poetry is that people think you’re not being serious, ‘it’s a risk you take’, he said. And I think that’s a much more modern stance, you know, I think these days we’re more comfortable with the idea that a poem can be simultaneously funny and serious, partly because we’re aware that that’s true of life as well as art.

So obviously ‘The Humming-bird’ isn’t as avant-garde or game-changing as The Waste Land, but I do think that there’s something subtly innovative and future-facing about Lawrence’s tone here. Because on the one hand that’s a very funny, throwaway ending: ‘Luckily for us.’ But it’s also absolutely true that if we were plunged back into prehistory, or if all those fossilised specimens in the Natural History Museum suddenly came to life, we’d be absolutely terrified and rightly so.

So to me, the humour here almost feels like a guard-rail, or the fences at the zoo. Looking at Lawrence’s hummingbird through the lens of his whimsical humour, or ‘the wrong end of the telescope of time’, is like eyeballing a lion through bulletproof glass. You know it’s safe, but a part of you is still scared witless.

OK talking of telescopes and lenses, I think it’s time we zoomed in on some of the details of this poem, because it has this deceptive casualness of tone, but it’s actually very cleverly constructed. And there are some amazing sound effects that I think are key to the way it works. Have another listen to this:

I can imagine, in some otherworld

Primeval-dumb, far back

In that most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed,

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

Listen to those long yawning vowels, ‘In that most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed’. You can feel the ancient jungle yawning and stretching and scratching itself and then lapsing back into unconsciousness. It really captures the weirdness an non-human-ness of this primeval world, where there’s no history, there hasn’t been much time for things to evolve, and there’s not much happening, there’s a lot of stillness and space. And on the one hand, it feels kind of delicious, like the jungle is lazing about and luxuriating. But on the other hand, it’s mildly horrific, this vegetable kingdom where ‘life was a heave of Matter, half inanimate’.

And then, in the midst of this awful stillness, with all the gasping and humming and flopping about:

It’s like a sports car in an advert, zooming through these avenues of trees. Or like the speeder bikes in Return of the Jedi, zipping between the huge tree trunks in the forest of Endor. And notice that Lawrence gives the hummingbird the most fantastic verbs: he ‘raced down the avenues’, he ‘chipped off in brilliance’, he ‘went whizzing through the slow, vast, succulent stems’, he ‘flashed ahead of creation’, he ‘pierced the slow vegetable veins’; and at the end he is ‘jabbing’ and ‘terrifying’ us.

So there’s this wonderful contrast between, as I say, these yawning vowels of ‘that most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed’, life as a ‘heave of Matter, half-inanimate’, and the hummingbird that goes ‘whizzing’ through it all.

Lawrence says that ‘life was a heave of Matter, half inanimate’, it was this vast amorphous mass, and then the hummingbird is ‘This little bit chipped off in brilliance’. Notice all the little short ‘i’ sounds in, ‘This little bit chipped off in brilliance’. It’s like the old phrase, a chip off the old block, that has broken off and gone whizzing and zooming and piercing and flashing about. It’s like life has suddenly got a bit of independence, a speck of individuality, and there’s a real exhilaration in this image of a hummingbird zipping about in the empty forest, like being the only car on a racetrack.

And what is powering this powering his little racing car? Have a listen to the engine:

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

I know what you’re thinking. That’s right! It’s a dactylic trimeter, isn’t it? So a dactyl is a is a metrical foot, unit of analysis, bit like a bar in music, a way of analysing the metrical pattern. And we’re more familiar with the iamb, in the iambic pentameter, that goes do DO, do DO, do DO, do DO, do DO. So that’s an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one.

But the dactyl starts with a stressed syllable, followed by two unstressed ones. So it goes DO do do. DO do do. DO do do. Humming-birds. Raced down the. Avenues.

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

And the ‘trimeter’ part just means you’ve got three feet. So instead of the pentameter where you have five feet, in the trimeter you have three feet – dactylic trimeter.

And the regular pulsing beat of this line really stands out, because the poem is not written in a regular metre. It’s in free verse, which means there’s no regular beat, the rhythms are driven by the natural and expressive patterns of stress in the words and phrases.

And that makes the hummingbird’s burst of energy all the more powerful, because in the midst of all this lazing about and gasping and humming, and language flopping about in its own lackadaisical cadences, we’ve got this engine starting up, this DO do do. DO do do. DO do do. It’s like you’re lazing in the garden on a summer’s day and your neighbour suddenly cranks up their hedge-trimmer.

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

So there’s this contrast between the vegetative world of the jungle and the chipper little hummingbird, which we can hear in the rhythms of the poem. And listen to how Lawrence locates the emergence of the hummingbird in time:

Before anything had a soul,

While life was a heave of Matter, half inanimate,

This little bit chipped off in brilliance

So Lawrence tells us this takes place ‘Before anything had a soul’, and to me at least, this lack of a soul sounds like a blessed relief. And it’s worth remembering that Lawrence grew up at the tail end of the Victorian area era, which was a period when there was an awful lot public controversy and private wrestling between the tenets of Christianity and the theory of evolution. There was a sense that science was stripping humans of their divine souls, and relegating the whole of creation to dead matter. And that caused an awful lot of grief and anguish among devout, or formerly devout, Victorians.

But here, it’s as if for Lawrence, the soul feels more like a burden, and it’s a relief to cast it off, or at least to go back to a time before anyone thought of it. And there’s a delightful freedom in being nothing more than ‘a little bit chipped off in brilliance’.

And you obviously can’t hear it when I read the poem, but if you look at the text, you’ll see he’s capitalised the word ‘Matter’ in ‘While life was a heave of Matter’. So he clearly wants to draw attention to this word, as if he’s emphasising physical matter in contrast to the soul. (Which, interestingly, he does not capitalise.) And if we look at that capital letter, and we think about the etymology of the word ‘matter’, then we may recall that it is historically related to the Latin word ‘mater’, meaning ‘mother’, which also gives us English words such as ‘maternal’ and ‘maternity’.

So knowing this, and also knowing Lawrence’s interest in mythology, I don’t think it’s a huge leap to suggest that Lawrence is half-thinking of ‘Magna Mater’, the Great Goddess of the ancient world, who survives vestigially in English as ‘Mother Nature’, and ‘Mother Earth’.

There’s definitely a sense in the poem of the primeval jungle as a feminine space, with its oozing liquids and capacious avenues. And you don’t have to be a Freudian to pick up on the phallic suggestiveness of the hummingbird, with his masculine pronouns, penetrating the avenues and piercing ‘the slow vegetable veins’. So the hummingbird feels like a kind of masculine independent consciousness arising inside the ‘half inanimate’ body of Mother Nature.

So there are a lot of contrasts in this poem, present and past, matter and spirit, male and female, that combine to dramatic effect. And Lawrence ramps this up in the final two verses, by introducing the element of size:

Probably he was big

As mosses, and little lizards, they say, were once big.

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

We look at him through the wrong end of the long telescope of Time,

Luckily for us.

So the whole of the ‘otherworld’ of the poem is now turned upside down and inside out. Not just in the shifting sizes of the hummingbird and mosses and lizards, but also the idea of looking ‘through the wrong end of the long telescope of Time’. Because the telescope metaphor mixes up space and time, and produces a delightfully queasy effect. If you think about that line too long it will probably give you vertigo. It’s a really weird and disorienting feeling, like something out of H. P. Lovecraft – if you’ve ever read his story The Call of Cthulhu, you will never forget the hideously non-Euclidean geometry and perspective of the landscape around Cthulhu’s lair.

And then to cap it all, after the cosmic horror of the telescope and the jabbing monster, we get this throwaway last line, ‘Luckily for us’. And it’s funny and it’s cheeky, but it’s also quite unsettling. Because behind the bulletproof glass of Lawrence’s humour, he’s really pointing out that we’re living in a relatively tame and placid era, but the merest blink of a few million years ago, this planet was a ‘most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed’, and inhabited by jabbing terrifying monsters who would inhale us like gnats.

And Lawrence sounds like he’s only joshing, but he’s holding out that telescope with a teasing grin, and asking if we’re brave enough to take a look.

Humming-bird

by D. H. Lawrence

I can imagine, in some otherworld

Primeval-dumb, far back

In that most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed,

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

Before anything had a soul,

While life was a heave of Matter, half inanimate,

This little bit chipped off in brilliance

And went whizzing through the slow, vast, succulent stems.

I believe there were no flowers, then

In the world where the humming-bird flashed ahead of creation.

I believe he pierced the slow vegetable veins with his long beak.

Probably he was big

As mosses, and little lizards, they say, were once big.

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

We look at him through the wrong end of the long telescope of Time,

Luckily for us.

D. H. Lawrence

D.H. Lawrence was an English novelist and poet who was born in 1885 and died in 1930. His work was controversial in his lifetime, particularly his treatment of sex in his novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover, so when he died, most of the obituaries in the English press were hostile. However, E.M. Forster offered a dissenting view, when he described Lawrence as ‘the greatest imaginative novelist of our generation’. Although he was better known as a novelist, Lawrence wrote almost 800 poems and was an advocate of free verse at a time when it was relatively new and unorthodox. This, as well as his descriptions of animals and plants, made him an influential figure in 20th century poetry.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith

Episode 70 Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith Matthew Buckley Smith reads ‘Drinking Ode’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: MidlifeAvailable from: Midlife is available from: The publisher: Measure Press Amazon: UK | US...

The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden

Episode 69 The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John DrydenMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage about the Great Fire of London from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.Poet John DrydenReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Great Fire of London,...

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

Thank you, Mark, for a beautiful light-hearted appraisal of a poem I’ve always loved. You’ve brought this sparkling little verse to life alright for those who are unfamiliar with it.

You mention Lawrence being a bit earnest, hectoring and preachy elsewhere in his work. That has never been any deterrent to me. In fact, there is so much wrong with the world today. . .it has become so hellishly insane and full of lies that I believe we need all of Lawrence’s earnestness and hectoring preachiness more than ever. It could be our salvation yet!

Thank you Dave, the poem does sparkle, doesn’t it?

I agree with you that Lawrentian earnestness makes a lot of sense as a response to the state of the world. And a lot of great prose is written from that stance… I just don’t think it makes for good poetry. Our preachiest poets tend to write their best poetry when they are at their least moralistic. E.g. Milton.