Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 26

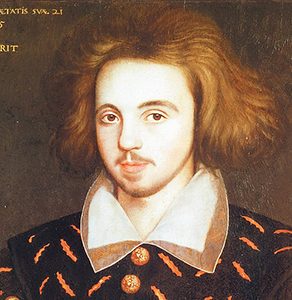

From Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Mark McGuinness reads and discusses a speech from Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe.

Poet

Christopher Marlowe

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

From Doctor Faustus, Act 5, Scene 1

by Christopher Marlowe

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss —

Her lips suck forth my soul: see, where it flies!

Come, Helen, come, give me my soul again.

Here will I dwell, for heaven is in these lips,

And all is dross that is not Helena.

I will be Paris, and for love of thee,

Instead of Troy, shall Wittenberg be sack’d;

And I will combat with weak Menelaus,

And wear thy colours on my plumed crest;

Yea, I will wound Achilles in the heel,

And then return to Helen for a kiss.

O, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars;

Brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter

When he appear’d to hapless Semele;

More lovely than the monarch of the sky

In wanton Arethusa’s azur’d arms;

And none but thou shalt be my paramour!

Podcast transcript

On an autumn evening about fifteen years ago, close to the stroke of midnight, I found myself entering a graveyard in Deptford in the company of two poets: Mick Delap, who you may remember from Episode 13 of this podcast, and Paddy Bushe, who is a wonderful Irish poet.

Being poets, we were there to find one grave in particular, and it took us a few minutes of stumbling about in the dark. Then I suddenly found myself facing a stone slab on the churchyard wall, illuminated by a shaft of moonlight so that I could read the words:

Near this spot lie the mortal remains of Christopher Marlowe, who met his untimely death in Deptford on May 30th 1593.

Cut is the branch that might have grown fall straight.

It felt like an absurdly poetic moment; three poets in the graveyard at midnight, and that line from Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus, really hit home for me:

Cut is the branch that might have grown fall straight.

It struck me that those words are completely apt for Marlowe himself, as well as the tragic hero of his play.

Christopher Marlowe was a brilliant comet lighting up the sky of Elizabethan drama. He’s often described as an important precursor of Shakespeare. But he was only baptised a couple of months before Shakespeare, so they were almost exact contemporaries. And in the 1580s and early 1590s they were rival playwrights, very likely friends, or maybe frenemies.

They played off each other, they strove to outdo each other, they very likely egged each other on, and it’s fair to say that Shakespeare would not have been quite the Shakespeare we know without Marlowe’s influence.

But we shouldn’t just relegate Marlowe to an also-ran or accessory to the Bard’s success. He was an amazing poet and playwright in his own right. And the passage that I’ve just read, is representative of everything that is enthralling and exhilarating, and also dangerous and problematic about Marlowe.

He must have been an extraordinarily unsettling person to get to know. You know, sometimes you meet somebody and you think, ‘Okay, this, this person is trouble’. You would definitely have got that feeling from Marlowe. He was charismatic, mercurial, shocking and unforgettable – and you can say the same about his plays.

He delighted in creating a spectacle on stage, in taking things to extremes. His first big hit, Tamberlaine the Great, was an orgy of violence, with one brutal conquest after another, with none of the compunction or remorse on the part of the conqueror, or the empathy or pity for the conquered, that we get in Shakespeare.

His next play, The Jew of Malta, is still controversial today, because to us, it is repulsively antisemitic. But for the original Elizabethan audience, what would have been provocative wasn’t so much the antisemitism, which they would have taken for granted, but having a Jew on stage, in the title role. Jews had been officially banished from England in 1290 and were not officially readmitted until 1650; so although there were Jews in the country in the 1580s, they were pretty invisible, so Marlowe was being deliberately inflammatory in placing a Jewish character centre stage.

In Edward II, Marlowe puts homosexuality front and centre, in the character of King Edward and his lover Piers Gaveston, at a time of extreme homophobia, when homosexual acts were punishable by death. It contains an infamously violent scene, that I am not going to describe on this podcast, but it’s fair to say Marlowe gave the subject the most sensational treatment he could. And it’s pretty clear that Marlowe himself was gay, so he was really flirting with danger in putting on a public play of this kind.

And Marlowe keeps going with the sensationalism… in The Massacre at Paris he describes a wave of mob violence in Paris, which took place only twenty years before he put it on stage, where thousands of Huguenots, French Protestants, were murdered by Catholics. And in the middle of the English Reformation, at a time of extreme religious and political tension, this was a powder keg of a subject.

And in Doctor Faustus, which we are looking at today, and which I think is his greatest play, he went for what was probably the ultimate taboo for his audience. Because Elizabethan England was a deeply and strictly Christian society. You could be fined for not going to church on a Sunday. You could be executed for blasphemy or heresy.

And by the way, Marlowe had a reputation as an atheist. There are reports of his opinions about religion that are so shocking that I wouldn’t dream of repeating them on today’s podcast, not even with my explicit tag. You can read them by Googling ‘the Baines note’, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Anyway, what he does in Doctor Faustus is, he presents the ultimate sin for a Christian: a man who sells his soul to the devil.

So Doctor Faustus is a learned scholar in Wittenberg, in Germany, who performs a magical ritual on stage and summons up a demon, Mephistophilis. He signs a contract in his own blood, where he gives his body and soul to Lucifer, the Prince of Devils, in exchange for 24 years of life with unlimited magical powers. So he can do whatever he wants, he can travel the earth on a dragon’s back, he can have Kings and Popes and Emperors at his command, he can have all the money and women and knowledge he desires.

Which of course would have been unspeakably shocking to his audience, but also utterly compelling. In a society full of rules and restrictions, he put all their forbidden desires on stage.

So that’s the context and some of the content of Marlowe’s drama. But what was the rocket fuel that powered it? Poetry.

When Marlowe was writing for the stage, there were none of the fancy lighting rigs or elaborate sets and costumes that we take for granted when we go to the theatre. The stage would look very bare and plain to our eyes, especially now we’re used to CGI in the movies and TV, and even on stage sometimes.

And to me, what makes this such an exciting period is that what supplied the special effects, the CGI, the industrial light and magic, for the biggest form of popular entertainment, was poetry.

Famously, at the start of Shakespeare’s Henry V, the Chorus comes on and apologises for the ‘unworthy scaffold’ of the playhouse and asks the audience to ‘Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts.’:

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i’ th’ receiving earth.

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

So the poetry is the thing that sparks the imagination of the audience, so when they listen to the actors they start to picture the characters and see the scene come to life.

And not just any poetry, but a particular kind of poetry. The unrhymed iambic pentameter that these days we call blank verse, one of the most famous and enduring verse forms in English. I actually can’t believe we’ve got this far into the podcast without talking about blank verse. But rest assured, we are remedying that now.

So blank verse is composed of lines of iambic pentameter, which we’ve already encountered in several episodes: the famous ti TUM ti TUM ti TUM ti TUM ti TUM. So just to recap, an iamb is a type of metrical foot, a unit of analysis, where you have an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one: ti TUM. For example, the first two syllables of today’s speech by Marlowe: ‘is THIS’. Then the next two syllables are the next iambic foot: ‘the FACE’.

And when we put them all together, we get: [exaggerated pronunciation] ‘Was THIS the FACE that LAUNCH’D a THOUsand SHIPS’. Or, a little more naturally and less robotically:

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

Okay, can you hear that rhythm? Can you start to feel it in your bones? We’re going to be hearing a lot more of it, so we want to fix it in our minds and sense it in our gut.

And the ‘blank’ part of ‘blank verse’ simply means that it’s not rhymed. Which was still new and innovative when Marlowe started writing. The first person to write blank verse in English was Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey, in the 1540s. But being an Earl, he was far too posh to be writing drama for the vulgar public stage. So until the late 16th century, audiences would have been used to hearing plays in rhyming verse, usually in couplets. So all these pairs of lines would have been tied up neatly in a bow, with a rhyme at the end of the line.

Bits of this style survive in Marlowe’s writing, like this, which is the start of a prologue to The Jew of Malta, which was recited before a performance at Queen Elizabeth’s court:

We know not how our play may pass this stage,

But by the best of poets in that age

The Malta Jew had being and was made;

And he then by the best of actors play’d:

So as you can hear, we’re in the land of doggerel, and it’s hard to see how Marlowe or Shakespeare could have reached the heights they did, if they had stuck to this style.

And when blank verse came along, it sounded new and strange, and I believe it was originally supposed to be trying to recreate the exotic effect of certain types of continental or classical poetry. It would have sounded a bit foreign, a bit chic.

But what the playwrights discovered, was that blank verse is an incredibly powerful and expressive vehicle for dramatic speech. When you don’t have the artificiality of rhyme, you can get closer to the illusion of real speech. Now, of course, to us, it still sounds incredibly formal and stilted and old fashioned, but you’ve got to put it in the context. At the time, it was very much a loosening of the poetic strictures.

And the reason we’re starting our blank verse mini-series on the podcast with Marlowe is because he took the pretty rigid and regular blank verse that was being written by other playwrights, and started to shake it up, to bring in some expressive variation. And in doing so, he was able to make his characters start to sound like individuals. Up to that point, everyone pretty well sounded the same on stage, the actors were speaking a part rather than playing a character.

One of Shakespeare’s greatest achievements as a dramatic poet was to take this even further than Marlowe, to really mess with the regularity of blank verse and make it incredibly flexible and varied and expressive. And we’re going to look at what Shakespeare did next month, but we’re starting with Marlowe today, where you can hear the underlying pattern of the verse very clearly.

So this speech from Doctor Faustus is a great place to start our exploration of blank verse and I think we can all agree this is a pretty extraordinary piece of poetry, whatever the technical considerations.

I mean, you probably already knew that famous first line, ‘Was this the face that launched a thousand ships’, even if you didn’t know it was by Marlowe. It’s one of those magical lines that have entered the language and almost become proverbial.

So to give you some context, this is from Act 5, Scene 1, when Faustus has asked Mephistophilis, his tame demon,to summon up the shade of Helen of Troy because he’s decided that only she will do for his ‘paramour’. Helen’s beauty of course was legendary in the ancient world, and so it was her face that attracted Prince Paris of Troy and led him to abduct her and take hear back to his city, away from her husband, the Greek king Menelaus. So Helen’s face, by extension, according to Marlowe, launched the thousand ships of the Greeks, who were understandably incensed by Paris’s actions, and who were determined to take the city of Troy – also known as Ilium – and recapture Helen. And that was the beginning of the Trojan War.

And isn’t it just extraordinary the way Marlowe has compressed the whole of this story, and its background and inciting incident, to a single unforgettable line?

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships

And throughout this speech, the verse sizzles with energy and sparkles with magic:

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss —

Her lips suck forth my soul: see, where it flies!

And later on, we get:

O, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars;

I mean come on, as poetry lovers, how could we not be seduced by writing like this?

And to see how Marlowe is using the blank verse for expressive effect, let’s start by listening to those first two lines again:

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

So we can hear that very regular iambic pentameter, like a drumbeat, can we not? In his elegy on Shakespeare, Ben Jonson refers to ‘Marlowe’s mighty line’ and we can see what he means. It’s the dominant rhythmic pattern in this speech and in all of Marlowe’s plays, full of energy and power and momentum. And it can sound a bit monotonous to us, especially as we’re more used to Shakespeare. But listen for what comes next:

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss —

Can you hear that burst of energy in the phrase ‘make me immortal with a kiss’? Faustus is clearly getting excited at the prospect of a kiss, and that comes across in the rhythm here. And if we look closely at that line, we can see that Marlowe has added an extra unstressed syllable into the metre, after the word ‘make’. If he’d wanted to, he could easily have kept to the regular iambic metre, by using a two-syllable word instead of the three-syllable ‘immortal’. He could have written:

Sweet Helen, make me deathless with a kiss —

But notice how much flatter this line is? So by adding that extra syllable, Marlowe makes the actor skip over the two unstressed syllables, ‘me’ and ‘im-’, the first syllable of ‘immortal’. So the actor has to put a bit of extra energy into it, as if he’s crossing a stream via stepping-stones, and there’s a bigger gap between two of the stones so he has to do a little jump:

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss —

Can you hear that? And obviously the alliteration on ‘make’ and ‘mortal’ adds a bit of extra pizazz.

So just three lines in, Marlowe has established the blank verse metre but he’s also staring to vary it for dramatic effect. And then in the next line, we get:

Her lips suck forth my soul: see, where it flies!

So the first three feet, ‘Her lips suck forth my soul’, reestablish the regular iambic beat, before we get to that terrific ending: ‘see, where it flies!’ Which is perfectly mimetic, is it not, of the soul flying off before us? So how does Marlowe do this?

By a trick called a ‘reversed foot’. If he wanted to keep to the strict iambic metre, he could have ended the line with something like ‘now see, it flies!’, with the expected stress on the second syllable of ‘now see’. But by reversing this pattern, he puts the stress on the first syllable of ‘See, where’. So we get a similar effect to the previous line, where the actor has to jump nimbly over two unstressed syllables, to get from the stress on ‘see’ to the stress on ‘flies’:

Her lips suck forth my soul: see, where it flies!

So this reversed, foot, the opposite of an iamb, is called called a trochee, or trochaic foot. Instead of ‘ti TUM’, it goes ‘TUM ti’.

We encounter it again later in the speech:

And I will combat with weak Menelaus,

And wear thy colours on my plumed crest;

Yea, I will wound Achilles in the heel,

And then return to Helen for a kiss.

O, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars;

Brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter

So we hear the regular beat in these two lines:

And I will combat with weak Menelaus,

And wear thy colours on my plumed crest;

But then Marlowe shifts gears and the next line starts with a bang:

Yea, I will wound Achilles in the heel,

Can you hear that strong stress on ‘Yea’, the first syllable? So it’s another reversed foot. And the most common place for a reversed foot is right here, at the start of a line, where it can be very effective in kicking the line off with emphasis. It’s like a swimmer at the start of a new length, pushing off with their feet against the side of the pool.

And kicking off at the start of a line is entirely appropriate when Faustus is talking about wounding and killing Achilles, the greatest warrior of the Trojan War. I mean, if you’re not going to put some oomph into it then, when are you? So we get the martial vigour of:

Yea, I will wound Achilles in the heel,

Which is then followed by a return to regular iambic pentameter in the next line:

And then return to Helen for a kiss.

And of course, within the conventional gender roles of the 16th century, this shift would have felt natural to the audience, because they would have instinctively felt the thrusting power of that initial trochee to be consonant with the masculine world of military prowess; and the more regular and gentle iambic next line would have felt appropriate to what they thought of as the feminine domestic sphere, as the warrior returns home from battle to claim a kiss.

But trochees are not only good for bludgeoning warriors to death. They can also express intense Romantic passion:

O, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars;

Brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter

Can you hear that? That’s right, Marlowe begins three lines in a row with a trochee – ‘O, thou’, ‘CLAD in’, and ‘BRIGHTer’. So he’s really revving up the engine of the verse and letting us know that Faustus is being swept of his feet by his feelings. And I don’t know about you, but as a poetry lover, I find it pretty easy to be swept off my feet by verse like this.

Just one final detail about the metre here, before we’re all metred out. When you listen to this speech, it’s probably quite easy to tell where the lines begin and end, even though you can’t see them written down. And even though, as we’ve seen, there is no rhyme at the end of the line in blank verse, to let us know where we are. The reason why it’s easy to pick out the lines is because they are what’s called ‘end-stopped’. That just means that the end of a line coincides with the end of a grammatical phrase.

So:

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

End of line, end of a phrase.

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

End of another line, end of another phrase. And so on. For most of the lines in this speech, the end of the line is also the end of a phrase, so the effect is of having lots of units stacked on top of each other, rather than a smoothly flowing stream. And this is very typical of the verse drama of the 1580s, because, remember, blank verse was a new form and playwrights were just getting used to having no rhyme to hold onto at the end of the line.

But occasionally, Marlowe lets the sense run on from one line to another, so that the line break occurs in the middle of a phrase:

O, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars;

Can you hear that? The end of the line comes with ‘evening air’, but then the phrase continues into the next line, so that we learn that it’s not just ‘evening air’, but ‘evening air / Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars’, which is obviously an upgrade. Technically, this is called enjambment.

And surprise is key to the effect of the enjambment – it’s as though we thought ‘evening air’ was all there was, that was pretty good, and then suddenly this whole vista of stars opens up, as if a cloud has slid out of the way and revealed them. And of course it’s entirely appropriate for Marlowe to deploy this effect here, as he wants a bit of poetic lift-off with the extravagant praise for Helen.

We’ll come back to this pattern of end-stopping vs enjambment, when we look at Shakespeare next month; I just wanted to highlight this feature in Marlowe, so we can see how Shakespeare takes it further.

Anyway. Marlowe’s genius is not confined to metre; his poetry also draws a lot of its power from his rhetoric. Everything in this speech, like most things in his plays, is taken to extremes.

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss —

Really? I mean, don’t get me wrong, we’ve all had some good kisses! But to make you immortal with a kiss, that’s pretty bold, even for a poet!

Here will I dwell, for heaven is in these lips,

And all is dross that is not Helena.

Poets have a well-deserved reputation for exaggeration, but even by those standards, Marlowe is overdoing it here. It’s one thing to say your mistress is heavenly, but it’s pretty extreme to say that everything else in the universe is dross, is rubbish.

And he goes on to boast that he’s going to fight the Greek king Menelaus and kill the great warrior Achilles, and he tells Helen she’s brighter than a thousand stars, brighter than Jupiter, not just the planet but the king of the ancient Roman gods, so he’s laying it on pretty thick. And he finishes up by saying ‘none but thou shalt be my paramour!’ In other words, no one is worthy of him and his vast ego but Helen of Troy, reputedly the most beautiful woman who ever lived.

And this is typical Marlowe. You’ll find this kind of high octane stuff in every play, if not every scene. He doesn’t let up. And in the theatre it’s thrilling but also, if I’m honest, a bit exhausting. Goodness knows what he was like after a few drinks.

So I think we can agree this speech is pretty intoxicating. And yet… I don’t know about you, but I have a bad feeling about this. You know, there’s something disturbing going on underneath the glittering surface of Marlowe’s poetry.

If we recall the context of this scene, Faustus is using magic so summon up Helen’s ghost. So that means when he says ‘make me immortal with a kiss’, he’s not asking – he’s commanding. And he’s compelling by force of magic. Otherwise, let’s face it, what on earth would Helen of Troy see in a geeky scholar from Wittenberg? So he’s forcing her to give him a kiss. And she’s been dead for 3,000 years. So that’s pretty creepy and horrible, isn’t it?

And again, Marlowe has peppered this speech with impressive-sounding classical references. Like most of the playwrights later known as the ‘University wits’, he was eager to show off his education. But once we examine these references a little closer, we may start to feel a bit queasy.

So starting with the Trojan war, Helen was taken from her husband King Menelaus by the Trojan prince Paris. Opinions differ among ancient Greek authors as to whether she went willingly or was taken by force. But she was basically taken by one man and and fought over by a lot of other men. And, as they saying goes, to the victor the spoils, because in those days women were considered the property of men. So when Faustus says ‘I will be Paris’, and boasts of winning her by killing Greeks, he sounds more like a conqueror than a lover.

Next, Marlowe alludes to ‘hapless Semele’, one of many women in classical mythology to be impregnated by ‘flaming Jupiter’, the king of the gods. And he finishes by talking about ‘wanton Arethusa’, which is pretty weird, because far from being ‘wanton’, Arethusa was in fact a chaste attendant of Artemis, the Greek goddess of chastity. Arethusa was a nymph pursued by the river god Alpheus, after she had rejected his advances, and who had to appeal to Artemis to help her escape from him.

So this speech by Faustus shimmers with the lustre of Romance, but if we look at the dramatic context, and the connotations of the classical references, as well as the syntax and the rhetoric, it sounds less like the language of love, and more like the language of command, of conquest and of dominion. So maybe on reflection, after re-reading the speech in the cold light of day, we don’t feel nearly as spellbound by Marlowe as we did the first time we heard the speech, when we were intoxicated by him telling us we glittered like a thousand stars.

And yet… as always with Marlowe, it’s not quite as simple as that. It might be tempting to say he’s harnessing patriarchal myths to reinforce Faustus’s dominion over Helen, but if we look at the speech again, it’s actually Helen who he’s comparing to ‘flaming Jupiter’, the king of the gods, and ‘the monarch of the sky’. So there’s a weird power dynamic where it’s not entirely clear who is dominating who.

And all the way through the speech we can also can pick up an undercurrent of fear beneath Faustus’s bravado. Looking at the appeal to Helen again, we might ask ourselves, why does Faustus keep going on about his soul?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss —

Her lips suck forth my soul: see, where it flies!

Come, Helen, come, give me my soul again.

It’s fairly obvious that anxiety about losing his soul is playing on Faustus’s mind here. You know, he’s looking for immortality, but of course, whatever Helen does with his soul he’s already sold it, and time is running out. And the end of the play without giving away too many spoilers, that chicken really comes home to roost and he becomes very much aware of the downside of that contract he signed. So in spite of all the big talk, it’s hard to escape the feeling Faustus knows he’s flirting with damnation.

And that’s something else Marlowe has in common with his character – he made a career of flirting with disaster. He was like a moth to a flame. He kept worrying at the most controversial, the most shocking, the most troubling subjects, and in the end of course, the flame snuffed him out.

Remember the inscription in the graveyard, referring to Marlowe’s ‘untimely death’ in Deptford? At just 29 years old, his death was certainly untimely. It was also grubby and violent. In those days Deptford was a particularly disreputable area on the outskirts of London. According to the inquest at the time, Marlowe had spent his final day eating and drinking with three companions in a house in Deptford. Then there was an argument over ‘the reckoning’, i.e. the bill, and one of his companions, Ingram Frizer, stabbed Marlowe above the right eye, killing him instantly.

So that’s the official explanation, but there are a lot of hints and theories that there may well have been other forces at play. For one thing, speculation going all the way back to Marlowe’s lifetime suggests that he may have been a spy, employed by Sir Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster general.

So it may not be a complete coincidence that Marlowe’s three companions on that fateful day had all been employed by either Francis Walsingham or his relative Sir Thomas Walsingham. It’s quite the rabbit hole, and if you’re interested in exploring it there’s a terrific book by Charles Nicholl called The Reckoning: the Murder of Christopher Marlowe.

Was Marlowe a spy? If so, was he forced into the service? Or did he make a voluntary agreement and come to regret it? We’ll never know for certain why he was killed but one thing is certain – whenever you read Marlowe or you watch one of his plays, you are in the presence of a man playing with fire

From Doctor Faustus, Act 5, Scene 1

by Christopher Marlowe

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss —

Her lips suck forth my soul: see, where it flies!

Come, Helen, come, give me my soul again.

Here will I dwell, for heaven is in these lips,

And all is dross that is not Helena.

I will be Paris, and for love of thee,

Instead of Troy, shall Wittenberg be sack’d;

And I will combat with weak Menelaus,

And wear thy colours on my plumed crest;

Yea, I will wound Achilles in the heel,

And then return to Helen for a kiss.

O, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars;

Brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter

When he appear’d to hapless Semele;

More lovely than the monarch of the sky

In wanton Arethusa’s azur’d arms;

And none but thou shalt be my paramour!

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe was an English poet, playwright and translator who was born in 1564 and died in 1593. His two-part play Tamberlaine the Great was a smash hit in the London theatre and a transformative influence on the direction of drama in English. His other plays included The Jew of Malta, Edward the Second, The Massacre at Paris and Doctor Faustus, and he was considered the foremost dramatist in the country by the time of his death. His poetry includes the unfinished narrative poem Hero and Leander, and the popular lyric ‘The Passionate Shepherd to his Love’, as well as translations from Ovid and Lucan. Mystery continues to surround the circumstances of his violent death on 30th May 1593. His remains are buried in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford, in London.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith

Episode 70 Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith Matthew Buckley Smith reads ‘Drinking Ode’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: MidlifeAvailable from: Midlife is available from: The publisher: Measure Press Amazon: UK | US...

The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden

Episode 69 The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John DrydenMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage about the Great Fire of London from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.Poet John DrydenReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Great Fire of London,...

0 Comments