Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 2

He Thinks of Those Who Have Spoken Evil of His Beloved

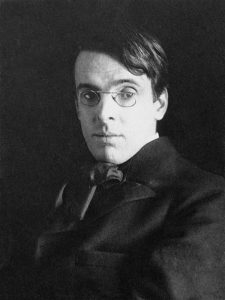

by W.B. Yeats

Poet

W.B. Yeats

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

He Thinks of Those Who Have Spoken Evil of His Beloved

by W.B. Yeats

Half close your eyelids, loosen your hair,

And dream about the great and their pride;

They have spoken against you everywhere,

But weigh this song with the great and their pride;

I made it out of a mouthful of air,

Their children’s children shall say they have lied.

Podcast transcript

This is the poem that gave this podcast its name, so it feels like the right poem to start with.

At first glance, this is yet another poem where the youthful Yeats is bigging up his Muse, Maud Gonne, by flattering her and disparaging anyone who has a bad word to say about her.

And I have to say, it doesn’t get off to a great start. I mean, why on earth would Maud Gonne want to half close her eyelids and loosen her hair and dream about people who have spoken against her everywhere?

Of course, the image of her with half-closed eyelids and loosened hair is entirely for Yeats’ benefit. It’s like he’s a pre-Raphaelite painter arranging his model for the best composition, which is maybe fine for a painter talking to a model, and was very much in keeping with the way poets addressed their beloveds in the 1890s, but it feels a bit uncomfortable to us hearing it now.

And the poem doesn’t tell us this, but I think we can safely assume that Yeats was thinking of Maud Gonne, the woman who inspired so much of his love poetry when he wrote this. And we know that she was a very spirited and independent-minded woman, very active in Irish Nationalist politics, which may well be why ‘the great’ have ‘spoken against [her] everywhere’.

Which makes it even more ridiculous that Yeats is expecting her to arrange herself decoratively for his contemplation. So it’s not hard to see why Maud Gonne called him ‘Silly Willie’.

But anyway. The poem does get better.

Clearly, Yeats is being ironic when he talks about ‘the great and their pride’. He means ‘great’ in the world’s eyes – people of power and influence, rather than great in the sense of being admirable or exemplary.

And ostensibly, the poem is about defending his friend from attack, and attaching shame to ‘the great and their pride’, by saying that ‘Their children’s children shall say they have lied.’ In other words, history is going to judge them harshly, so their so-called greatness will be short-lived.

And it’s so tempting, isn’t it? To say about someone who is abusing their power and status, that ‘future historians’ or ‘future generations’ will pronounce a damning verdict on them?

And it’s a pretty good last line, isn’t it? ‘Their children’s children shall say they have lied.’ And I’m guessing it must have been very satisfying for Yeats to write that line, with its clinching rhyme of pride and lied, giving him the feeling that he’d clinched the argument.

But if we look at the poem again, the poetry isn’t in the ending. It’s in the middle of the poem, after Yeats has stopped trying to arrange his model in the right pose, and before he starts pronouncing the judgment of future generations.

The poem is only six lines long. The first three lines set the scene:

Half close your eyelids, loosen your hair,

And dream about the great and their pride;

They have spoken against you everywhere,

And already we’re at the mid-point of the poem. Then the fourth line begins with a ‘but’, which suggests we’re going to hear something that will answer the slanders against his beloved. But what happens next is a surprise – we get this extraordinary image:

But weigh this song with the great and their pride;

I made it out of a mouthful of air.

Yeats invites his beloved – and us – to place poetry on the scales, as a counterbalance to the evils of the world, which are embodied in ‘the great and their pride’. And as if to emphasise the bravado and absurdity of the idea, he emphasises the lightness of his song, of the poem, by saying ‘I made it out of a mouthful of air’.

Yeats is literally correct when he says the poem is made of a mouthful of air. It is made of words, which are made of mouthfuls of air in the act of speaking. The poet is an artist who fashions his or her creations out of thin air. And poets have been doing this for thousands of years, long before the invention of writing.

And as I said in Episode 1, the word ‘inspiration’ comes from Latin, meaning ‘breathing in’. So there is a very ancient connection between the breath and poetry and the idea of the spirit or the soul or the metaphysical world.

So when I thought of creating a poetry podcast, this line from Yeats came into my mind. A Mouthful of Air seemed like the obvious name for the show.

But when I looked at the whole poem, especially that fourth line, ‘But weigh this song with the great and their pride’, it started to give me second thoughts.

Because these days, wherever you live, you probably don’t have to look far for ‘the great and their pride’ and the hatred and division they create. And here I am starting a poetry podcast. What can poetry offer to counterbalance all of that?

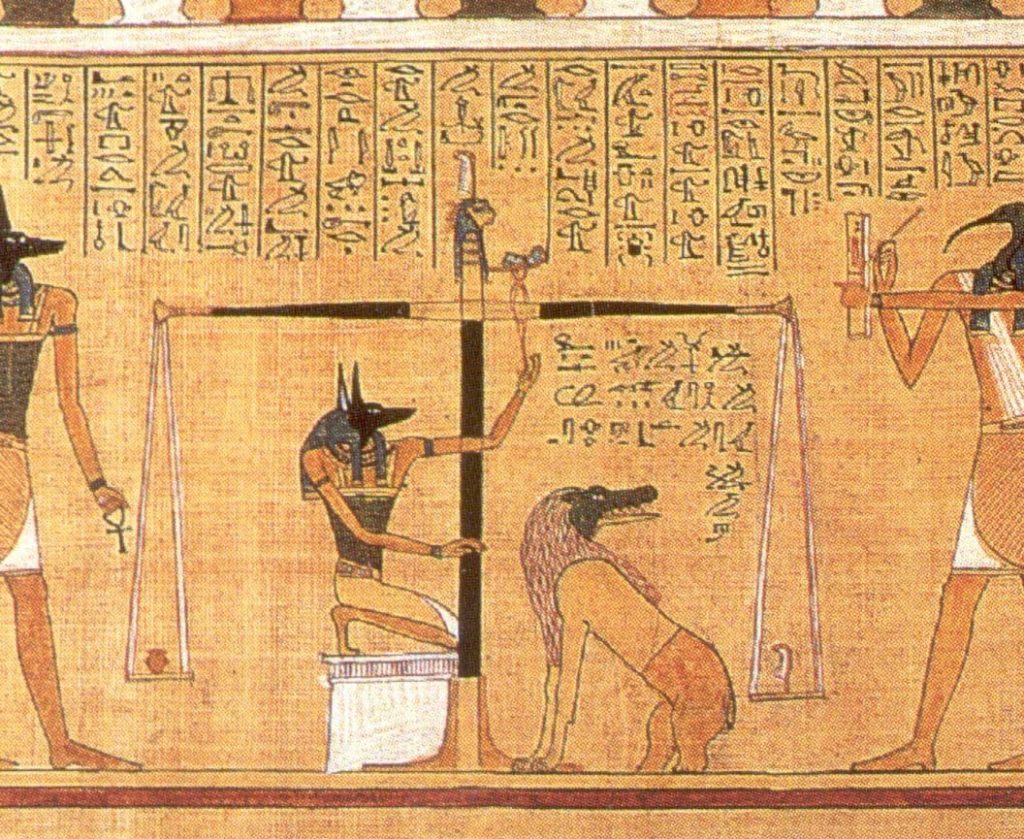

As I contemplated Yeats’ image, I remembered a visit to the World Museum in Liverpool a couple of years ago, where I was spellbound by a manuscript of the Egyptian Book of the Dead. This is an illustrated collection of magic spells intended to assist a dead person’s journey through the underworld and into the afterlife.

In one scene the scroll shows Anubis, the god of death, placing the dead person’s heart on a scale – on the other scale was a feather of the goddess Maat, who represented truth.

And waiting nearby was the demon Ammit, a hideous mixture of crocodile, lion and hippopotamus, with lots of claws and teeth and stinking breath and grinding stomachs. And when your heart was placed on the scale, if it heavier than the feather then it was thrown to Ammit who gobbled it up.

But if your heart was as light as a feather, because your good deeds outweighed your bad deeds… you passed the test and entered paradise.

It feels like an impossible test – how can you live in this world and see all the injustice and misery and suffering it contains, and not get caught up in it, and contribute to making it even worse? In other words, how can you live in the world and still have a heart as light as a feather? Yet the Book of the Dead suggests it is possible. Just as Yeats’ poem suggests that it is possible for poetry to provide something to counterbalance ‘the great and their pride’.

Poetry is one of the most insubstantial things in the world. A few words on a page. A mouthful of air that is gone in an instant. Poets are not usually found in positions of power. Yet a poem can live for thousands of years after the death of the poet. In the words of Samuel Johnson, poetry can help us to enjoy life and to endure it.

Maybe Yeats and whoever wrote the Book of the Dead were just hopeless Romantics. Maybe truth or beauty or virtue or whatever else poetry represents is just grist to the mill of the monster Ammit, who will gobble it up along with you and me and everything else in this world.

Or maybe there is something of real value in that other scale, as light as a feather and as insubstantial as a mouthful of air.

In which case, maybe you’d like to join me and Yeats and the Egyptian Dead-head, and let’s savour that mouthful of air together on this podcast, A Mouthful of Air.

He Thinks of Those Who Have Spoken Evil of His Beloved

by W.B. Yeats

Half close your eyelids, loosen your hair,

And dream about the great and their pride;

They have spoken against you everywhere,

But weigh this song with the great and their pride;

I made it out of a mouthful of air,

Their children’s children shall say they have lied.

W.B. Yeats

W.B. Yeats was an Irish poet and playwright who was born in 1865 and died in 1939. He was a leading figure in the Irish Literary Revival and helped to found the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. He was active in Irish Nationalist politics and later in life served as a Senator for the Irish Free State. In 1923 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith

Episode 70 Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith Matthew Buckley Smith reads ‘Drinking Ode’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: MidlifeAvailable from: Midlife is available from: The publisher: Measure Press Amazon: UK | US...

The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden

Episode 69 The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John DrydenMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage about the Great Fire of London from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.Poet John DrydenReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Great Fire of London,...

0 Comments