Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 27

Return to the Terminus by Kathy Pimlott

Kathy Pimlott reads from ‘Return to the Terminus’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.

This poem is from:

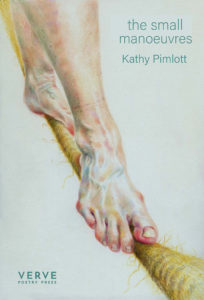

the small manoeuvres by Kathy Pimlott

Return to the Terminus

by Kathy Pimlott

Too often now I sway into the night,

that cosy winter dark between tea and

the turning out of pubs and cinemas,

a late traveller fogging a rattling bus.

See me on the upper deck with the dogs

and other coughers, taken up with smoking

in that sophisticated way, dragon-nostrils.

I shouldn’t keep going back, am already yellow

beyond scrubbing. These comfortable excursions

just won’t do while all the while life howls

for attention. Last year a clever man I knew

a bit, courted a death he didn’t believe in.

Visiting, face it, out of a desire to be blessed,

by happenstance I was invited into the scan,

into the intimacy of his scarred insides,

to witness a death sentence, 90% sure, but, ah,

that golden 10. First question: can I still

have a drink? He died, swollen, in a hard clutch.

And now this other man, mine, heads that way too.

But anyhow, look, here comes the whipsmart clippie

machine grazing her hip, its crank and buttons

primed for pernickety fares. Only she commands

the bell: one for stop, two sharp dings for go.

If I don’t tell you, how will you ever know about

that bronco ride of side benches, the fear of slipping

right off the bus as the driver speeds, skips stops, reckless

on corners, to the end of his shift? It’s late, so join me,

grip the pole, lean out into those bright, melancholy lights.

Interview transcript

Mark: Kathy, where did this poem come from?

Kathy: This poem is an amalgamation of two poems that I was writing simultaneously. One of them, I think you could say was sparked off by… Well, looking out of my window, I look onto a very busy main road where the buses come along. And I was looking out one night, and what I can see is I can see the upper deck of buses going past.

Mark: And you’re in central London, Right?

Kathy: I live in central London. Yes. I live in Covent Garden where it comes up to meet Soho. So, I’m very central. So, I was looking at the buses coming past and at night when it’s dark, as dark as it gets around here, which is not very dark and the lights are on, on the bus and you maybe get one or two people on the upper deck. And that’s who I can see because I’m on the second floor looking out of my window. And so, it was that seeing them and thinking about buses maybe 40, 50 years ago, when it was a different sort of bus. It was a bus called a Routemaster in London. But certainly, the same sort of bus all over England where the upper deck was for people who smoked. So, you went upstairs to smoke.

Also, if you had a dog that wasn’t a guide dog, you had to take your dog upstairs as well. And the experience of buses then was quite different. They did rattle along. They had a bus conductor or conductress who came round and issued your tickets. And the tickets weren’t all for a single price, they were very finely graded for however many stops you were going on. And the buses sort of, rattled around. And if you sat near the door, the door which was open, it was an open platform that you got on and off. And if you sat on the side benches near that door, and you had a particularly nippy driver, you did feel like you were going to get thrown off. When you were little, you feel like you’re going to get thrown off because the seats were a bit slidey as well.

Mark: And there’s that pole at the back, isn’t there?

Kathy: And there’s a pole on the platform. Yes.

Mark: I remember these in the late 90s when I lived in London, they were still going around. And it was always quite exciting to grab the pole and get on just as it was leaving. And I felt quite amazed that they were allowed to do it.

Kathy: Exactly. And then the bus conductors, as it came up to a stop, would hang out to see how many people were waiting to get on and whether there was enough room for them as well. Yes, it was a very exciting experience, those buses. So, really, I was thinking about that experience and the physical sensation of that experience. And at the same time, I was writing a poem about the death of a friend. And somebody said something. I think it was Suzannah Evans, a poet up in Sheffield, who writes a lot about the future. And she was having a conversation on social media and said that she was bored with poems about the past.

It’s difficult if you are an older person, because you’ve got more past than you’re likely to have future, and there’s still quite a lot to mind. So, it jolted me into thinking that point, you know, ‘All the time life howls for attention,’ while I’m doing all of this thinking back about the past and going through that material. So, that’s how it brought them two together, really. So, it’s an amalgamation of two. And then the work was to try and make them work as one poem.

Mark: Poets do like the past, don’t they? I mean, Wordsworth famously said that poetry is ‘emotion recollected in tranquility’. So, you have to experience something and then reflect and recollect and, I mean, that’s kind of part of the whole stance of a lot of poetry, isn’t it?

Kathy: I think so. I guess people have different reasons why they write. Mostly I think why I write is to try and make sense of things that are lodged in my head. And that might be a story or an image or a memory or an emotion. And a lot of that for me, is in the past, it’s what constitutes me really, it’s what happened to me over the last, nearly 70 years. So, yeah, there’s a lot of it there to work with, but I do understand for some people, their poetry is moving forwards into the future and addressing those issues that loom in front of us. I just don’t do that, is all I can say in the end. I just don’t do that.

Mark: But it’s a very kind of, human predicament, you know, the ‘I’ of the poem, who obviously we should be careful with identifying necessarily with the poet. But the start, the second verse, ‘I shouldn’t keep going back.’ And obviously, I’m curious about going back where? ‘I’m already yellow beyond scrubbing. And these comfortable excursions won’t do while all the while life howls for attention.’ I mean, that’s quite a human situation, is it, to be doing one thing and to be thinking, ‘I should really be doing something else.’?

Kathy: Yes. That’s where I thought I could fit the two poems together, was to, sort of, acknowledge what I’m doing is dibbling around in the past, not wallowing in it, but enjoying it. Enjoying the memory and the evocation of the sensation of this experience of being on a Routemaster. So, if I acknowledge it, then I can incorporate what’s happening now, which was this big event of death. So, the I there is me really, I think, saying, ‘Yeah, I can see why people say I shouldn’t do this, and I shouldn’t do that because these big things are happening now.’ And this big thing is a very personal thing, a personal thing, an individual dying. It’s not a universal cataclysm, it’s a very individual cataclysm. Yeah. So, that’s where the I of that comes in. So, it’s to say, ‘Yes, I know, I know what I’m doing. I know that there is all this stuff happening that I should be engaged with, and here I am engaged with it, but no, it’s too much for me, you know? Let’s go and look at the clippie who is the bus conductor.’

Mark: And again, the portrayal of the dying man is so human, you know: ‘That golden ten percent’, you know…

Kathy: Yeah, I know.

Mark. …even faced with the seemingly inevitable, ‘Can I still have a drink?’ I mean, that’s such a human response. And…

Kathy: I think it is. So, as they say, this actually happened, it did actually happen. In a lot of the poems that people write in the I, including me, it didn’t happen. It’s a construct that you build in order to examine something else, but this did actually happen. And I think it was important to have the actual detail of that because it is the highly individual response, which you know is a response that alcoholics everywhere are going to have in that situation, that they are. So, I wanted it to be there even though I feel it, I’m very uncomfortable with it. I’m very uncomfortable in using other people’s experience, but what I hope that I’m doing is doing the vividness of the life howling for attention there. That’s why I allowed myself to put that in.

Mark: Again, it’s always a question I think in poetry, how much of real life do you put in? And as a reader, how much of this is real? Because without giving the game away, you and I were chatting before we started recording. And there was one or two poems in the collection that I said, ‘Oh, that was amazing.’ And I thought it was a flight of fancy, but actually, it turned out to be true that readers discover those for themselves. But, if you’re reading Kathy’s book, be alert! I would say, because quite often, the truth seems to be stranger than fiction.

Kathy: Yeah. I think it is. I think it is. And that’s what makes it interesting, isn’t it? If it was all absolutely verifiable in every detail, fact-checked, it wouldn’t be so interesting.

Mark: So, you started off with two poems, and I wouldn’t have guessed that and I can see now. It looks to me like you’ve fitted them together very deftly. Because what I noticed was, obviously, it starts on the Routemaster, and then the speaker goes into this reflective mode, you know, ‘Last year a clever man I knew’ a bit. And that’s, you know, quite often we get on the bus, we drift off because someone else is driving. So, could you say something about that process of how you… What made you think, ‘Oh, I can put these two together even though there’s one’s about a bus and one’s about this dying man?’

Kathy: Well, I think it was to a degree that neither were working individually. So, I think it was… take the bussy bit, the bussy journey bit. I work with a workshopping group most Saturdays, a group of poets who… Well, we have done throughout the beginning of the lockdown, and they’re all over the country. They’re not London-based. So, I take my work there and workshop it. And I’d taken both poems, I think, and in both instances, they hadn’t quite worked. So, the bus one, I think the response that I remember was, it wasn’t said like this, but it was, ‘So what? Okay. You know, you’re talking about something, you’re talking about it very nicely, you know. It’s musical, it’s attractive, but so what? But so what?’ And I think the death…

Mark: ‘Where is this bus going?’

Kathy: Yeah. And this death one, the deathy one, I think I just hadn’t found the way through it yet. It probably was too much information. So, there were two poems there that weren’t quite working on their own. And the impetus to put them together was to acknowledge my proclivity towards a, sort of, not nostalgia because it’s not a love, but just an interest in the experiences of my past and my tendency to go there in order to write, in order to find things that I want to write about. As I said before, it was finding that intense experience of the now, which I think going into somebody’s death sentence is pretty much as intense as you can get really.

Mark: Yeah.

Kathy: And so, it seemed like an answer to the, ‘so whatness’ of the bus question. I would say that that was it. And looking at the deathy thing, well, subsequently, I had a much more personal death happen in my life. My husband died. And so, now, right now, I am examining all of that. So, I am writing a lot of extremely painful and depressing poems about death. So, I’ve been able to park the whole of that poem, which I’d segued into the bussy poem. Unfortunately, I have been able to park all of that and to spend more time looking at the effects of death in other work. So, yeah. So, that’s how they came together, that’s why they came together. How did I do it? Just by fiddling around, Mark, is how I did it.

Mark: To use the technical term. [Laughter]

Kathy: To use the technical term. Yeah.

Mark: I mean, it works beautifully because I guess, you’ve topped and tailed it with the ‘bussy bit’, which is, you know, quite satisfying from a, kind of, narrative perspective. And also, that personal death is in there in just one line, isn’t it?

Kathy: Yeah. Yeah.

Mark: And now this other man, mine, it’s that way too. And I’ve just realized when I’m saying that that’s why the speaker says, ‘But anyhow, look,’ and that’s the distraction, that anyhow is doing a lot of work, isn’t it?

Kathy: Yeah. Yeah. Yes, exactly. It is that, ‘No, I don’t want to think about this, you know. Let’s go and look at buses of the 1950s.’

Mark: Right. And it’s a glorious distraction. I mean, having ridden the Routemaster, not quite with all the smokers and the dogs up on the top deck, but there’s always something weird going on, on the top deck.

Kathy: It certainly was.

Mark: It’s so evocative, you know that one for stop, two sharp dings for go, and the bronco of the side benches and…

Kathy: And then what I think happens is… So, most of that, not necessarily in the exact way that it’s there, but most of that was already there in the, ‘So What?’ poem about the bus, but I think it gained something from the death bit in the… Sorry, this is terrible, isn’t it? The death bit in the middle. [Laughter.]

Mark: I mean this is how you have to think about it when you’re putting it together, isn’t it?

Kathy: I do. I do think about it. I think it gains because she becomes, the clippie, the bus conductor becomes something else. The bus becomes something else. Even though the detail of it is the bus, it does actually become something else, I think. And that happened not by me setting out to make that happen because that was there before. I injected the present day in it, but it just does becomes of a cast. A shadow is cast over it.

Mark: Yeah. Can I entice you to say anything more about what that something else might be?

Kathy: Well, I think yeah, it’s a journey towards dying in a certain sense, isn’t it? It’s the journey towards dying. It’s the lack of control. It’s the fear and exhilaration. And for me it is late. For me it is late, you know. As I say, I’m 70 this year. So it is late. So I’m saying, so, that ‘join me’ is that, you know, it’s really asking for leave to make these comfortable excursions, which in the end don’t turn out to be that comfortable, you know?

Mark: No, no.

Kathy: I know some people see writing about the past is quite cozy, but it’s not really, it’s not really. Even for those of us who’ve had a blessed life, it’s not that cozy.

Mark: Yeah. Because the bus is really going one way as we know from the title, don’t we? ‘The Terminus.’

Kathy: Yes. Yes.

Mark: Do you know what, the poem it reminded me of a bit was the Louis MacNeice poem, ‘Charon’ which…

Kathy: Do I know that one?

Mark: So, it starts off with a bus conductor going through London, and it gets stuck. And they get down to the river because London is so crowded. And he doesn’t say why London is so crowded. Then they get down to the Thames, and the bridges are blocked and there’s the ferryman and it’s Charon. [Laughter.]

Kathy: Oh my God!

Mark: And he looks at the traveler and he says, ‘If you want to die, you will have to pay for it.’ [Laughter.]

Kathy: Quite right too! That’s exactly right. That’s exactly right. ‘The Pernickety fares’, it’s exactly right.

Mark: That’s it, you know. You know, death and taxes, well, even beyond death, you’ve still got to keep paying! I mean, without laying it on too thick, it certainly felt, you say ‘something else’, it felt that it’s quite significant. You know, at the beginning, it’s almost like, the trainspotter’s or the bus spotter’s guide to the Routemaster. And at the end, you’ve still got all those details, but you’ve got the sense of this, this bus is gathering momentum and we’re being swept off our feet. And you can either be afraid of that, but actually, it’s wonderful that you’ve got that kind of Romantic lift: ‘Grip the pole, lean out into those bright melancholy lights.’ It’s like The Smiths’ song, ‘There Is a Light That Never Goes Out’, that we’re going to embrace that, or at least that’s what I got. Is that what…?

Kathy: Yeah, I think so. I think also for me, and I don’t think this is the case for any reader necessarily. It just takes me back to the initial impulse of looking out my window and seeing the lit upper deck of a bus, which is melancholy and bright and strange. And here in Central London at night, it is bright and melancholy to my mind. It is everywhere, everywhere you go at night here is very brightly lit. But it’s got an element of melancholy about it or maybe that’s just what happens when you get older, Mark. I don’t know. Everything turns melancholy.

Mark: It does, but to poets, there’s always a tinge of melancholy. Again makes me think of those and maybe it’s like the London version of the Edward Hopper paintings, where you’ve got all those bright-lit bars that look just so, kind of, devastatingly sad.

Kathy: Yeah. Yes, it is that. I think it is that. There is that element in it certainly upper decks at night where you’ve only got two people on do have exactly that same aura, that same feeling for the viewer.

Mark: Yes. With occasional fear. So, you’ve already talked a bit about how you put the bits together of the poem, just thinking about how you assembled it. And you’ve got this structure. So, if anybody’s listening to this, you haven’t seen the text yet, do obviously check it out on the website. But you’ve got four stanzas, seven lines each. Was that the original arrangement? Did that form evolve from something else?

Kathy: No, I don’t think so. I think both… I’m trying to remember. I think both of the poems that I used were blocky in this way. I don’t know that they were necessarily this number of lines, but they definitely weren’t couplets or triplets. I work a lot in couplets. I find I like the space that gives and the lightness, but the material of this seemed denser and buses are, sort of, that shape, that oblong shape.

Mark: Yeah. They’re quite four square, aren’t they?

Kathy: You know, so it’s that. So, I think I did start already blocky. And why did this go into seven lines? I don’t know. Because looking at the line breaks and where I was going to turn lines over and how little sense breaks come in, that’s just how it worked out. You know, you look at it and think, ‘Well, this could be, well, this could be.’ If I could just lose that one line, what this could be is four verses of seven lines, and how very annoying it is. One of them has got eight lines, and in that instance, you will find somewhere to take a line out or to squeeze a line. So, two lines, so it becomes one line. And I’m sure that I did do that at some point, but that would’ve been towards the end where I’ve, say, just got one line that’s really annoying, you know?

Mark: Yeah.

Kathy: And I’ll cut it out.

Mark: Like a tuft.

Kathy: Yes, exactly. It needs trimming. And either you just cut it all out or you find a way of knocking two lines together by getting rid of unnecessary words in it, however much you might love them.

Mark: Exactly. Sometimes they need to be sacrificed for the greater good.

Kathy: They do, don’t they?

Mark: And so, roughly, each stanza is a different scene, isn’t it? You start from the past and then you…

Kathy: Yeah, I think so. Yeah. Definitely, with the first stanza, that’s that, sort of, setting up the premise, isn’t it? And then the second one is allowing the present in. And then the third one is half and half really. It’s still carrying on and then go, ‘Oh no, I’m not going to look at that.’

Mark: That’s it. It’s like you don’t want to go too far into that scene and that train of thought. And, that’s the anyhow at the end, which is a real pivot.

Kathy: Yeah. So, that shifts that round. And then the last one is going back to the bus, but with a slightly new take, a new understanding of the bus, I think. None of this, Mark, is in my mind when I’m writing. None of this. I’m just writing. I’m just writing what I can remember and what I think about and where it takes me. I’m not thinking, ‘Oh, I know what I’ll do. I’ll do this and I’ll do that and I’ll do that.’ I’m not thinking that at all and I certainly wasn’t thinking that in relation to this poem. So, I start from free writing.

Mark: Were you like a duck to water with that attitude? Did it take you a while to, kind of, trust the writing part of you to get on with it without planning it ahead?

Kathy: I think once I’d learned that, once I knew that that was how you did it or how I did it and a lot of people did it that way, I’m not, sort of, saying this is my own invention. It’s not at all, but once I understood that that was a way of writing, that did work for me and does, continues to work for me very well. So, I will always start with, ‘There’s something I want to write about and I don’t know why I want to write about it.’ Sit down, you’re going to sit there for half an hour or three sides of A4, whichever is the longer, and you’re going to write. And you’re going to start off with the line that’s annoying you.

So, it might be an actual line, or it might just be, ‘I don’t know why I want to write about this, but something happened here and I want to, blah, blah, blah… ‘ And just carry on writing. And then looking at it and saying, ‘Is there anything there? Is there anything there?’ And then taking out that thing that you think is there and then writing again in that way. And then at some point, it starts to make a shape. And that’s when you then start, ‘Right. Okay. This is the work. This is the work.’

Mark: And that’s the exciting thing about poetry, isn’t it, but also, the scary thing.

Kathy: Yeah. Because it doesn’t always come to anything, you know. You can actually write quite a lot or, I can write quite a lot and it doesn’t come to anything, but it doesn’t matter.

Mark: Or even worse, maybe you could come to something and then feel the urge to say, ‘But anyhow.’

Kathy: Yes. Exactly. Exactly.

Mark: Which I think you’ve done just beautifully here, Kathy.

Kathy: Thank you.

Mark: I think you’ve taken us far enough down that road that almost we can fill in our own blanks.

Kathy: Yeah. I hope so.

Mark: And we will all have blanks. We’ll have more and more of them as life goes on. But also, the bits that aren’t blanks, you’ve given us so many great details to divert us with, especially in the description of the bus.

Kathy: Thank you, Mark. Part of what I like about writing, what I enjoy, is the sound of the words. So, for example, ‘Primed for Pernickety Fairs’ gives me a great deal of flesh.

Mark: And so it should, because it does for us too. It does for me at least.

Kathy: And, ‘Only she commands the bell. One for stop, two sharp dings for go.’ So that you just do that…

Mark: It’s beautifully mimetic, isn’t it?

Kathy: I like that. In a way, that pleasure in that is something quite different from what it’s about or anything like that. And I understand how I can get totally carried away in it. And I really have to cut things back a lot, because I get carried away in a pleasure of just language, of playing with the language both in terms of its rhythms and in terms of the actual… I don’t know, plosives, and the long vowels. How you put them together, how you have like a really long sinuous sentence that you don’t know is ever going to stop, and then you have to find a way of stopping it. And the use of breath, how you use breath, which you use in terms of how long you structure your sentences for, and things like that.

But you generate emotion through the breath, through the use of breath. Well, I do, for me reading it, and I hope the reader does too if they are sensitive to the punctuation, shall we say? Yes. So, that’s something.

Mark: Absolutely. And this is something I think has always struck me about your writing is there’s always lots of things to savor. You know, they’re quite sensual that some that you’re able to scribe. Like, there’s another poem where you’ve just got this great, it’s almost like an inventory of the pantry. And it’s just such a beautiful description of what it’s like to go into a real old-fashioned pantry and all the stuff that’s in there that you… I mean, I remember going to my grandmother’s pantry when I was small and just being eyes gawk at all this stuff. And the language that you use to evoke all kinds of things and actions throughout the book is… maybe I shouldn’t say this but, it’s a book of poetry that you can really enjoy reading. I’m not saying you don’t always enjoy reading all books of poetry, but there’s a lot of fun things in here.

Kathy: I hope so.

Mark: Yeah. There’s a lot of kind of sensuous pleasure…

Kathy: Yeah. I hope so.

Mark: …in the language.

Kathy: I hope so. Because, I mean, that is the joy of language, for me. It’s always been the joy of language, is just the playfulness of it and the feeling of it in the mouth. I love it. I just love it. So, it’s something that I have to be careful not to be too self-indulgent with because my God, I can go down that track forever.

Mark: Sure.

Kathy: So, I have to pull it back, but I want it there because why would you speak to others without sharing some of that pleasure?

Mark: Yeah. And why do it in poetry? Because it could be prose or, drawing or something, but this is… Yeah. If you’re going to do it in words, really do it in words.

Kathy: Yeah. Yeah. Yes.

So, thank you, Kathy. That feels like a lovely point to hear the poem again.

Return to the Terminus

by Kathy Pimlott

Too often now I sway into the night,

that cosy winter dark between tea and

the turning out of pubs and cinemas,

a late traveller fogging a rattling bus.

See me on the upper deck with the dogs

and other coughers, taken up with smoking

in that sophisticated way, dragon-nostrils.

I shouldn’t keep going back, am already yellow

beyond scrubbing. These comfortable excursions

just won’t do while all the while life howls

for attention. Last year a clever man I knew

a bit, courted a death he didn’t believe in.

Visiting, face it, out of a desire to be blessed,

by happenstance I was invited into the scan,

into the intimacy of his scarred insides,

to witness a death sentence, 90% sure, but, ah,

that golden 10. First question: can I still

have a drink? He died, swollen, in a hard clutch.

And now this other man, mine, heads that way too.

But anyhow, look, here comes the whipsmart clippie

machine grazing her hip, its crank and buttons

primed for pernickety fares. Only she commands

the bell: one for stop, two sharp dings for go.

If I don’t tell you, how will you ever know about

that bronco ride of side benches, the fear of slipping

right off the bus as the driver speeds, skips stops, reckless

on corners, to the end of his shift? It’s late, so join me,

grip the pole, lean out into those bright, melancholy lights.

the small manoeuvres

‘Return to the Terminus’ by Kathy Pimlott is from the small manoeuvres published by Verve Poetry Press.

the small manoeuvres is available from:

The publisher: Verve Poetry Press

Kathy Pimlott

‘Return to the Terminus’ is from Kathy Pimlott’s debut full collection, the small manoeuvres, published by Verve Poetry Press in April 2022.

She also has two pamphlets with The Emma Press, Elastic Glue (2019) and Goose Fair Night (2016). Her poems have been published widely in magazines and anthologies. Her poem ‘Closeups in Lockdown’ was one of just 20 chosen for inclusion in the Poetry Archive’s Now! Wordview 2020 Collection. Kathy was born and raised in Nottingham but has spent the last 45+ years living and working in Covent Garden, specifically Seven Dials, home of the broadsheet and the ballad. She has been a social worker and community activist, worked on a political and financial risk journal, in arts television and artist development. She currently earns her living as the administrator of a community-led charitable trust.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith

Episode 70 Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith Matthew Buckley Smith reads ‘Drinking Ode’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: MidlifeAvailable from: Midlife is available from: The publisher: Measure Press Amazon: UK | US...

The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden

Episode 69 The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John DrydenMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage about the Great Fire of London from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.Poet John DrydenReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Great Fire of London,...

0 Comments