Podcast: Play in new window | Download

The Larder

by Judy Brown

In the shop’s moist basement the red wines lay

prone in their cool dormitory. Beyond

the jars of lobster bisque and canned truffle sauce,

both Lancashires sat squat on their wood: Tasty

and Mild like a pair of underground kings.

No satisfaction in breaching the waxed cloth,

breaking the stiff robes they were buried in.

Only the owner had the right to draw the cutting wire

twice through the horizontal before quartering.

It was ritual, to bear each portion upstairs to the shop.

Later we’d peel the cloth off the soft edge

and unpuzzle the grain of the clotted blank face.

Down there, too, was where they kept the unripe moons

which were soft as what’s inside a baby’s unfused skull.

In the dark they would salt to rock and start to spin.

When at last the old satellite has worn to a nub,

an uncut cheese will rise, white and purposeful

with the sun’s reflected buttermilk light, to do its work.

Think of the store of teeth a shark is born with;

which, one by one, drift to the front of the mouth

to take their turn to be the ones to shine, to bite.

Interview transcript

Mark: Judy, where did this poem come from?

Judy: It has got a genesis back, I suppose, when I was at school. But the reason, probably, that it was written… and I nearly went and dug out my folder that has all the drafts in, but it’s at the back of a store…

Mark: Appropriately!

Judy: But it was written as part of a poem conversation that I used to hold with Katrina Naomi. And I’m feeling that the trigger was actually something like, Taking it to the Wire or that sort of phrase, because the first draft was called something like, ‘Drawing the Wire Through It’. So, I think it was the idea of wires that possibly sort of brought this to mind. But it has a history that’s a bit… jumps back probably five years from that. So, that was about 2018.

But I was put in residence at the Wordsworth Trust in 2013, and I had been at school in the Lake District when I was a teenager. Because it was a tourist area, we all had, like, Saturday and Sunday jobs. And then we all worked through the summer. And when I was at university, I used to work through the summer, lots of things, chambermaiding, and kind of hotel reception, clearing up. But for a number of years, I had a job in this place called the Lakeland Barbecue, which sold meat and cheese. And so, the setting for this is, in fact, the Lakeland Barbecue, the downstairs food storage area. But when I was at the Wordsworth Trust, I went back to look for the Lakeland Barbecue to see if I could find the building and couldn’t even identify the building that the shop had been in.

Mark: And just to backtrack a bit, you mentioned doing a poetry dialogue with Katrina Naomi. For any listeners who’ve never participated in such a thing, could you explain what it is?

Judy: Yeah. It was a conversation that took the form just of poems. So, one of us would send the other a poem, and the other person would swap, basically, poems every month and that you would respond to anything you wanted in the poem. It didn’t really matter whether it was a word, a mood, subject matter, anything. You could choose what you bounce off, which was really nice having that openness. I’m not very good with anything that’s very structured.

Mark: So it was a bit like poets’ tennis.

Judy: Sort of. And also, a bit like an exchange of letters, but in the form of… well, we had letters as well, but there was a lot of communication that happened just inside the poems that we swapped, which was quite interesting.

Mark: Right. And did any other poems from that dialogue end up in the book?

Judy: Oh, lots of them, yes. Lots and lots. I think it’s partly because you often have something that… I mean, this was something I had intended to write about when I was in Grasmere, because the shop was in bonus, which is not too far away, but I never did. And somehow the idea of the wire just got me there. So, I think it often provided a triangulation point for maybe a couple of things you’d intended to write about all along.

Mark: Okay. So, that was the initial impetus, and then that opened up this memory. But I think one of the really lovely things about this poem is that it’s kind of almost any basement, isn’t it? I mean, it just took me back to childhood memories, in particular, of going under the house or under the old church that we used to attend and into what felt like a crypt. It was full of pots and pans and paints and stuff. But it’s such a mysterious kind of primeval space, isn’t it, going into the earth?

Judy: Yeah, you’re absolutely right. It is, isn’t it? And it’s a sort of place where the rules are slightly different. Yeah, that’s quite true.

Mark: Almost like the shop… there’s the shop front, there’s what’s displayed to the air and to the street, and presumably, the shopkeeper being as professional and welcoming and shipshape as possible up the top. But when you go downstairs, this is kind of the engine room of the enterprise, isn’t it? This is where you get to see all the stuff that is privileged access. As well, I think, it’s part of the fun of this poem that we get to see behind the scenes and these wonderful details like the jars of lobster bisque and truffle sauce. And maybe for our international listeners, you could tell us what both Lancashires are, if they haven’t guessed.

Judy: Yes. Two types of cheese that we… we sold a lot of cheeses in the shop, but the Lancashire was by far the most popular. So, the two Lancashires were the kind of uncrowned royalty of this cellar, because the owners would buy them in great, big, sort of, foot-and-a-half high cheeses wrapped in wax cloth. And they would have to be cut into slices before they could even be taken upstairs. So, we sold more of those than anything else.

And this form of Lancashire… you know, the Lancashire comes in two flavours, tasty and mild, which was the first thing you ever had to ask the customers, which you learned, if they wanted Lancashire, you would have to say, ‘Tasty or mild?’ You know, tasty was more popular, but mild was my favourite.

Mark: And it’s, like you say in the poem, they’re like a pair of underground kings’. It’s like a mausoleum, isn’t it? Or a pyramid. And again, talking to privileged access, you, presumably, the speaker of the poem is this shop assistant, is not allowed the satisfaction of ‘breaching the waxed cloth’ or ‘breaking the stiff robes that they were buried in’. Only the owner had the right to do that. So, even down here, the rules are different, but there are still rules, aren’t there?

Judy: Yes. There was quite a lot. The owners who ran the shop were quite strict about how things happened. And there was a ceremony about these cheeses because they were so big, so much bigger than the Stilton, which they also had. They were always at the centre of this wooden, kind of… what’s the word? What is that word? Huge, great, big sort of wooden table down there. And there were quite a lot of things that we weren’t supposed to do.

And so, I think, the importance of the cheese was also sort of impressed on us by the owners who used to get really kind of agitated, understandably, if anyone mis-measured cheese. Because people would ask you for a quarter and you’d have to judge it by eye. So there was an element of stress about the whole business because, I believe, it was a kind of exotic cheese that you didn’t do very often. It used to be a bit of a do if you put too much and somebody didn’t want six ounces. So, yeah, it was tied to the shop.

Mark: And also, in getting… the word ‘acolyte’ is coming to mind in the way you were kind of tending the cheeses?

Judy: Yes, I absolutely do agree. And I think there’s also that sense of ancientness. I don’t know where this phrase comes from, but that thing that… the further underground you go, that you are looking for your own traces by then, I can’t remember who says that. Maybe it was either Freud or Jung in a dream perhaps, where they went into the basement of the house and found some bones and then not finding their own bones among them, went on. This is a phrase that stuck in my head. So, I think there’s always that sense of ancientness that comes to you as you go underground, isn’t there? And I suppose cheese and wine have a kind of gourmet ancientness too.

Mark: Yeah. I mean, they’re not quite timeless, but they certainly go back a lot further than maybe the canned truffle sauce. You know, there’s a medieval feel to this. You’ve got the underground kings and the stiff robes. And I couldn’t help noticing, you’ve got ‘drawing and quartering’ in here, which is quite scary. ‘Only the owner had the right to draw the cutting wire / twice through the horizontal before quartering.’

Judy: You’re right, you know, because there is that sense, isn’t there, of the cheese as a body, it’s such a huge thing, this cheese. So, yes. I think you’re often not… I wasn’t aware of that set of kind of medieval-type languages, but yeah, I agree with you.

Mark: I only picked up on the drawing and quartering this morning, possibly, because I’ve been reading some grizzly history. But, that whole torture and execution thing, that was just part of everyday life in those days. And then you say ‘It was ritual to bear each portion upstairs to the shop’. So, it really does feel like you’re going back in time, you’re going into another dimension here. At the same time, you’ve got all these wonderfully, realistic details of the basement of the shop.

Judy: Yes. I suppose it did have a slightly elemental quality to me, the kind of roasting of chickens on spits, which they also did. And all of us had these, like, two-foot-long ham knives, with our names carved into the handles so we didn’t use somebody else’s knife, and all that measuring by eye and stuff. Yes, I suppose that that possibly might have led me towards a slightly trencherman kind of set of vocabulary.

Mark: Well, you’d certainly want to tread carefully in this place, wouldn’t you, with all the equipment and the rules and the scary things down below? And at this point, it really starts to get quite macabre, which I love. You’ve got the unripe moons, ‘soft as what’s inside a baby’s unfused skull’. I mean, that is just delightfully weird. I mean, did that just come to you or… ?

Judy: I think the poem came quite formed relatively in terms of the trajectory of its ideas, but a lot of that, probably, comes from something which I don’t know a lot about but I have seen done, the making of cheese and how you start with these almost brain-like curds and they gradually become denser and harder as the ageing process sort of happens inside the kind of mausoleum outside.

Mark: And then we’ve got, in the dark, they would ‘start to rock’, ‘salt to rock’, sorry, ‘and start to spin’. So, is this the cheeses coming alive?

Judy: It’s changing its nature. I think it’s almost becoming less alive as it becomes more mineral, perhaps. Because it’s becoming something other than a sort of body and almost becoming a planet in a way. So, I think it’s moving away from the world of bodies and ancestors into something more… not necessarily more celestial, but colder, something colder and more central or more governing, I guess, perhaps. It’s really interesting what somebody else sort of sees in it that you don’t know that you put in. And then, of course, you think, ‘Yes, that does feel right, but that wasn’t a thing I thought less. Yes, I’ll insert that.’

Mark: Yeah, that’s the fun of poetry, isn’t it, that you find more in than you’ve put into it very often? And then we’ve got this ‘old satellite… worn to a nub’, and the ‘uncut cheese will rise white and purposeful / with the sun’s reflected buttermilk light, to do its work’. Again, it’s moving about, it’s rising, I guess, like the moon? And I can’t help wondering about what is its work going to be.

Judy: Yes. I guess, by the time the poem ends, you don’t entirely know, necessary work. But whether it’s going to be good work, I don’t know.

Mark: Yeah. My spine is tingling at this point. And then, this wonderful, wonderful ending that’s so unexpected, where you say, ‘Think of the store of teeth’ – and I’m noticing the pun on ‘store’ there now for the first time – ‘a shark is born with; / which one-by-one drift to the front of the mouth’. The idea of the teeth drifting to the front of the mouth ‘to take their turn to be the ones to shine, to bite’ – what a wonderful word to end on.

Judy: It’s funny how you start with something and it just takes you. I can see that there are… from the practical trigger, there are certain emblems that are often drawn to in poems, teeth, very often, moons, very often, and I suppose, eating. I think, initially, I had the idea that it was rats actually that had teeth that moved to the front of the mouth, but it isn’t, it was sharks, which actually fitted better, because I was keen for it to be correct. Because that idea of teeth moving forward in to sort of do their biting was just so kind of powerful to me.

Because, in a sense, there is a power in this subterranean place that’s both sort of archaic and elemental, but that’s also like connected to the grownup world. You know, you kind of have to approach the cheeses with deference. And I suppose the ending is concerned with that, is concerned with the kind of things that you can do when you set yourself off shining and biting.

Mark: Well, I mean, what could be more terrifying than emerging from the darkness of this basement than a shark? I mean, it’s a real stuff of nightmares at this point. And it really struck me that the end, the bite – because, we bite the cheese, don’t we? But by the end, through kind of figurative language, it’s almost like you could say the cheese is biting back. We think we are in control and suddenly we are the ones being confronted with this nightmareish mouthful of teeth that are just moving forward and forward and forward, and they keep coming.

Judy: And governing the tides, I suppose. I hadn’t actually thought… the interesting thing about having this sort of conversation is something that I had not thought about this poem, but I think it’s probably there, is because this was, like, a Saturday job I had when I was at school. I think there is some element of it that is a little bit dealing with the question of, like, coming of age. And although the cheeses and the moons and so on are all person, there’s this kind of sense of creaturely burgeoning. I think in some ways it’s kind of a celebration that the idea too at that age is, like, you want to be the one whose turn it is to shine and to bite as well. And you don’t know yet what it’s going to feel like.

Mark: Yes. Yeah, I can see that now. There’s a lot in this basement, isn’t there, when you start to have a look around?

Judy: I guess that you often find that the paradox, that conflict of sort of ancient hierarchies and kings and rules and stuff, and then also, that sense of breaking free, which I am connecting, I think, in my mind subconsciously when I wrote this. But I think it’s definitely there with that sense of, when you’re asking yourself, ‘Who am I going to be?’

Mark: Yes. Yeah. That’s a really great way of looking at it.

Judy: Because it’s about newness and replacement of what is worn out, I suppose.

Mark: Yeah, absolutely. And picking up on that question, who am I going to be? I mean, if we apply it to the poem, how close is this, what we have on the page, to the first version?

Judy: I couldn’t dig out the very first handwritten version, but I did have a look at the first typed version. And I think it was probably written a bit faster than it might normally have been because of this conversation process. But the first handwritten version seemed to have, basically… I mean, it sounds odd to call it an argument, but in my head, I see it as an argument, that there is a movement from one idea to another, even if it’s an argument through metaphor. And that was pretty much intact in the first version even though the title was different, which gave it a different feel, I suppose.

I mean, obviously, I’ve done quite a lot, you know. You read it out loud, you kind of care very carefully about the syntax, and if it doesn’t feel quite right, to make sure that the pace is right, and the way that one thing kind of moves into another. Because I knew I was pushing the envelope with the movement of the argument from one thing to another and these strange sort of both animate and inanimate creatures. So, I really wanted to make sure that was natural, hopefully. But it’s quite hard if those steps in that kind of argument don’t happen naturally. It’s quite hard to fill them in later. So, it was a single thought in some ways in the beginning.

Mark: Yeah. I mean, because it is quite daring from where you start to where you get to. And I think, one way that you managed to do this is that you anchor it… and this is something, I think, you do a lot in your poetry. You have got these wonderful qualities of observation that you can anchor the reality of the poem very much in the specific detail.

So, we start off in the shop’s moist basement, a great adjective, the red wines lay prone in their cool dormitory. And then, as I said, the lobster bisque and the canned truffle sauce and the tasty and mild are italicised in the text, like, brand names on labels. And so, it’s absolutely realistic and convincing. And I think, once you’ve kind of got the reader in that space where we trust you and we trust what you show us, then you can take us further and further and further out into the realms of imagination.

Judy: That’s a lovely thing to say, because I think that… I strongly feel that I want things to be both real and have their symbolic forms. I mean, in my head, it doesn’t stop being a shop with some cheeses and the kind of slightly anxious owner not wanting anything to be wasted, but at the same time, it is because I think that’s the way you think all your life. But I think you do particularly think it at, sort of, 14, 15, that everything means more than just what it is. And I think it does. And so, that’s lovely what you say because that is really what I’m aiming for in my poems a lot of the time.

Mark: So, it’s realistic…

Judy: That things should not lose their down-to-earth nature, but at the same time, their other nature should be visible, I suppose.

Mark: Absolutely. I get that from this and lots of your other poems. Okay. So, you started with that through line of metaphorical argument, and you had a different title. Are we allowed to know what the original title was?

Judy: The original title was, ‘Taking the Wire to It.’

Mark: Which is more edgy, isn’t it?

Judy: Yes. But it perhaps gave me freedom to, like, take things apart more than I might have done if I had started writing a nostalgic poem about being a teenager working in a cheese shop and slightly a Tudor shop full of legs of pork and beef and… not legs of beef, but, you know, massive joints of beef is not a very delicate experience.

Mark: No. But when you start from ‘The Larder’, you know, you can really sneak up on us a lot more, can’t you? If you start with the wire, then we’re already slightly on edge, but ‘The Larder’ is quite welcoming, isn’t it? And then you kind of softly take us further and further out into uncharted space.

Judy: I think you’re right, because I think the kind of slight dissection kind of element of the wire, I didn’t really like that, because this is like a space where everything comes from. You know, it’s where bodies turn into themselves. It’s a kind of source place. And so, I felt ‘The Larder’ had a bit more to do with the real move of the poem, which is partly celebratory and partly about being a store for whatever’s coming next in life. I don’t think I put those thoughts into my head in.

Mark: No, but there’s a richness as a cornucopia of the larder, isn’t it? Is that a very English word? Would international listeners recognise that? Maybe they would call it ‘the store’ or something?

Judy: Pantry?

Mark: But certainly, I remember we had a larder, pantry. It’s that ballpark, isn’t it? And so, how did it evolve once you’d got that basic through-line?

Judy: I think, often with this sort of poem, if you have got the back… I mean, it’s difficult. If you haven’t got the through-line, it’s difficult to find it. But if you have it in the first version, then what I would normally try and do is just make it as smooth as possible and as coherent as possible. But, making the jumps just the right kind of stretch so that there’s a bit of a stretch but not too much so that nobody falls, that’s the aim.

Mark: We don’t want to lose any readers through the cracks!

Judy: You’re not always sure you get there, but that’s the aim, to sort of make it more into what it is, make it a better version of what it is.

Mark: And I think, if you’re listening and you have a look at the text on the website, it’s all one block. It’s like one, long, blank verse-ish… it’s not blank verse, but it’s got that feeling when you look at it on the page. And, I guess, it’s like the basement itself, everything is crammed together in there. You know, you don’t get any respite to go from one space to another if it was all neat stanzas.

Judy: Yes, definitely. And I suppose it’s also… I mean, I do have sounds. I don’t think I necessarily have as varied a range of forms that I use as some poets do, but this is definitely one that I use, probably, in circumstances where something depends on having a forward pace or a kind of argument that you want somebody to follow, almost to surprise themselves at where they’re going to end up. If the journey were broken up, that would interfere with the effect that I’m getting, I suppose. And in this case, because there is the thing that’s really happening, that you are going down the stairs into this deeper place and discovering things, it feels right that each step should be equal, which is the case in that sort of block.

Mark: I see. Yes. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Very much. Well, thank you, Judy. This has been a wonderful deep dive into the basement. So maybe this would be a good point for us to listen to the poem again and step back down into that space. Thank you.

Judy: Thank you very much, Mark.

The Larder

by Judy Brown

In the shop’s moist basement the red wines lay

prone in their cool dormitory. Beyond

the jars of lobster bisque and canned truffle sauce,

both Lancashires sat squat on their wood: Tasty

and Mild like a pair of underground kings.

No satisfaction in breaching the waxed cloth,

breaking the stiff robes they were buried in.

Only the owner had the right to draw the cutting wire

twice through the horizontal before quartering.

It was ritual, to bear each portion upstairs to the shop.

Later we’d peel the cloth off the soft edge

and unpuzzle the grain of the clotted blank face.

Down there, too, was where they kept the unripe moons

which were soft as what’s inside a baby’s unfused skull.

In the dark they would salt to rock and start to spin.

When at last the old satellite has worn to a nub,

an uncut cheese will rise, white and purposeful

with the sun’s reflected buttermilk light, to do its work.

Think of the store of teeth a shark is born with;

which, one by one, drift to the front of the mouth

to take their turn to be the ones to shine, to bite.

Judy Brown

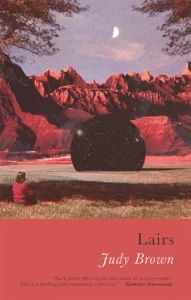

Judy Brown’s latest collection Lairs is published by Seren. Her earlier collections were Loudness (shortlisted for the Forward and Aldeburgh prizes for best first collection) and Crowd Sensations (shortlisted for the Ledbury Forte Prize). Judy has been Poet in Residence at the Wordsworth Trust, a 2014 Writer-in-Residence at Gladstone’s Library and, most recently, held an Arts & Culture Fellowship at Exeter University, spending summer 2019 with a team of mathematicians who work on uncertainty quantification. In the past she has worked as a lawyer in London and Hong Kong.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith

Episode 70 Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith Matthew Buckley Smith reads ‘Drinking Ode’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: MidlifeAvailable from: Midlife is available from: The publisher: Measure Press Amazon: UK | US...

The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden

Episode 69 The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John DrydenMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage about the Great Fire of London from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.Poet John DrydenReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Great Fire of London,...

0 Comments