Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 61

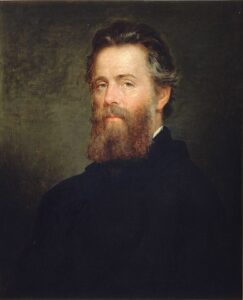

The Maldive Shark by Herman Melville

Mark McGuinness reads and discusses The Maldive Shark by Herman Melville.

Poet

Herman Melville

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

The Maldive Shark

By Herman Melville

About the Shark, phlegmatical one,

Pale sot of the Maldive sea,

The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim,

How alert in attendance be.

From his saw-pit of mouth, from his charnel of maw

They have nothing of harm to dread,

But liquidly glide on his ghastly flank

Or before his Gorgonian head;

Or lurk in the port of serrated teeth

In white triple tiers of glittering gates,

And there find a haven when peril’s abroad,

An asylum in jaws of the Fates!

They are friends; and friendly they guide him to prey,

Yet never partake of the treat—

Eyes and brains to the dotard lethargic and dull,

Pale ravener of horrible meat.

Podcast transcript

This is a gloriously ghastly poem that’s somehow repulsive yet joyful at the same time.

As we saw back in Episode 36 about Tennyson’s poem ‘The Kraken’, monsters from the deep are a perennial fascination for poets and other writers. Back in that episode we placed Tennyson’s Kraken in a lineage of sea monsters spanning The Odyssey, the Bible, Milton, Jules Verne, and H. P. Lovecraft as well as monster movies like Jaws and The Creature from the Black Lagoon. And, of course, the white whale that featured in Herman Melville’s magnum opus, his novel, Moby-Dick.

But unlike a lot of these writers, Melville’s writings about the sea were based on firsthand experience. He had gone to sea as a young man, as a common sailor, on merchant ships and whaling voyages. So he wasn’t exaggerating when he wrote in one of his other poems, ‘I have been / ’twixt the whale’s black fluke, and the shark’s white fin’. So if Moby Dick is his tribute to the whale, then this is his much shorter but also very memorable treatment of the shark.

I’m not sure exactly which species of shark he’s referring to in this poem. Unlike Melville, my knowledge of sharks is mercifully theoretical. ‘Maldive Shark’ doesn’t seem to be the name of a particular species of shark, so we should probably take the poem’s title to mean ‘a shark in the Maldives’. But if you know more about sharks than I do I would love to hear from you, what species of shark you think it might be.

OK diving straight in, so to speak, to the first line of the poem, ‘About the shark, phlegmatical one’, I think there’s a nice syntactic ambiguity here, because it’s natural for us to read this line as ‘I’m saying something about the shark’, but that’s not what he means, as the following lines reveal:

About the Shark, phlegmatical one,

Pale sot of the Maldive sea,

The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim,

How alert in attendance be.

So what he’s really saying isn’t, ‘I’m writing something about the shark’, but that the ‘sleek little pilot fish’ are in attendance ‘about’ the shark, swimming around him. And what he’s describing is a fascinating natural phenomenon known as symbiosis, where you have two species that collaborate for mutual benefit, in a way that can seem puzzling to human beings.

So the pilot fish are relatively small fish that are often seen swimming around sharks. The shark does not eat the fish, even though apparently they are quite tasty, and in return for not being eaten, and the protection that they receive by being within the orbit of a shark, the pilot fish clean the shark – they nibble off the parasites from its body and even clean its teeth, by gobbling up the little bits of leftover after its meal. Which on the face of it looks like an extremely dangerous manoeuvre, but somehow the pilot fish get away with it, it is extremely rare for sharks to eat their pilot fish.

The pilot fish get their name because they look like little pilot boats guiding ships into port or through dangerous waters, and they were once mistakenly thought to be leading the sharks to their prey. So Melville describes them as ‘eyes and brains’ of the shark, that ‘guide him to prey’, which may not be technically true, but there’s no need for that to spoil a good poem. The essential fact is that they live together for mutual benefit.

And for me, the joy and the fun of the poem comes from the contrast between these two creatures and the way Melville contrasts them in his use of language.

So the shark is described as the ‘phlegmatical one’, a reference to the ancient theory of medicine based on the four humours, of which the human body was supposed to be made up, and which led to the four basic temperaments – you could be sanguine, choleric, melancholic or phlegmatic, which according to the Oxford Dictionary meant that you were ‘not easily excited to feeling or action; dull, sluggish, apathetic; stolidly, calm and self possessed’.

Melville also describes the shark as a ‘sot’, a foolish or stupid person, and also a ‘dotard, lethargic and dull’, meaning senile, stupid or foolish. So Melville is painting a picture of the shark as not the sharpest tool in the box. Not the most quick witted or quick moving.

By contrast, he gives us ‘The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim’, who are ‘alert in attendance’, and ‘liquidly glide on his ghastly flank’. So they’re very nimble and quick moving and by implication quick witted.

I want to pick up on that little word, ‘The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim’ – he uses ‘azure’, the old fashioned heraldic term for ‘blue’, and it’s it it so much better than ‘blue’ as a way of describing the fish? That little ‘z’ suggests, to me at least, the striped patterning, the pointy fins, the aerodynamic design and the sheer zippiness of the pilot fish. Imagine if Melville has described the fish as ‘blue and slim’, we’d have none of those qualities. They wouldn’t sound nearly so angular and zippy, would they.

So the pilot fish are ‘sleek’ and ‘little’, ‘azure and slim’, nimble little words that mimic the look and feel of the fish. They ‘liquidly glide on his ghastly flank’ – isn’t that a wonderful sound, ‘liquidly glide’, with the ‘l’s rubbing and sliding against the consonants?

But the words that stand out in the description of the shark are very different: ‘phlegmatic’, ‘lethargic’, ‘Gorgonian’ – really ornate, ostentatious words, with roots in ancient Greek, that feel really heavy and slow and forbidding, just like Melville’s shark.

So the the Gorgon, of course, in Greek mythology, was a female monster with snakes for hair and if you saw the Gorgon’s head then you were petrified, turned to stone. And most of us would be petrified in the modern sense of the word if we saw the shark’s head up close, but amazingly, the pilot fish have nothing to fear.

Later in the poem, Melville also compares the shark to the ‘Fates’, the Moirai, also from Greek mythology, who were responsible for ensuring everyone lived out their destiny as it had been assigned to them from the beginning.

So the presence of these figures from Greek mythology, as well as the use of words with roots in ancient Greek, reinforces the sense of the shark as a really old and mysterious and sinister.

And this contrast between the shark and the pilot fish runs right through the poem, not just in the diction but also in the rhythm and the tone.

So, if you look at the poem on the page or the website, it doesn’t set up any great rhythmic expectations. There are 16 lines, but they aren’t laid out in stanzas, they’re all lumped together in a block. So, at first glance, it looks like your typical common or garden block of 20th century free verse. But of course when we hear it read out loud, then we can hear a pretty strong ballad metre.

So ballad metre is a traditional form, used for narrative poems, that we looked at back in Episode 22, about the anonymous ballad ‘The Unquiet Grave’. Ballads are usually composed in quatrains, four-line stanzas, alternating four beats then three beats per line, and a rhyme on the second and fourth lines of each stanza:

About the Shark, phlegmatical one,

Pale sot of the Maldive sea,

The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim,

How alert in attendance be.

Can you hear that? Four beats, as in, ‘About the Shark, phlegmatical one,’ followed by three beats, as in, ‘Pale sot of the Maldive sea,’, to exaggerate slightly.

So that’s the tune, if you like, that Melville is humming and it feels very appropriate to use ballad metre for this poem, because sailors’ tales and adventures at sea are the stock and trade of a lot of traditional ballads, quite a few old anthologies included ballads and sea shanties between the same covers. And one of the most famous ballads of all, of course, is Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

The beats are the important thing in ballad metre, you don’t need to count the unstressed syllables between the beats, so it’s quite an elastic and flexible metre. So it’s not typically as regular as iambic metre, for example, which alternates stressed and unstressed syllables in a set pattern.

Having said that, it is possible to write a ballad in iambic metre, you simply alternate lines with four and three iambic feet. And quite a few ballads tend to gravitate towards iambic metre, even if the poet isn’t writing strictly in iambics, because it’s a natural thing to find yourself doing, to have a single unstressed syllable between each beat.

For example, here’s a line from ‘The Unquiet Grave’ that can be scanned as a perfect iambic tetrameter, ti TUM ti TUM ti TUM ti TUM:

‘My breast it is as cold as clay,

But Melville’s little ballad doesn’t fall into this iambic pattern. Instead of having a single unstressed syllable between the beats, it has lots of instances of two unstressed syllables before a beat. Like this:

From his saw-pit of mouth, from his charnel of maw

This line scans as a perfect anapaestic tetrameter, meaning four anapaestic feet. An anapaest is a metrical unit with two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed one. ‘From his saw’, is an anapaest. And so is ‘-pit of mouth’, and so on.

And even though Melville is free to have as many unstressed syllables as he wants between his stresses, as the poem goes on, we find more and more anapaests creeping in: there’s only one anapaest in each of the first two lines, but after that, there are at least two anapaests in every line, there are two perfect anapaestic tetrameters and one anapaestic trimeter.

Have a listen to the second quatrain, where almost every foot is anapaestic, and you can hear it’s distinctive jaunty rhythm:

From his saw-pit of mouth, from his charnel of maw

They have nothing of harm to dread,

But liquidly glide on his ghastly flank

Or before his Gorgonian head;

It sounds more like a song than a story, doesn’t it? And there’s no narrative progression in the poem, it’s just a exuberantly extended description. So Melville is using the ballad form for lyric, rather than narrative poetry.

So as usual, the obvious question is: why is the poet doing this? Why is this particular metrical pattern coming to the fore in this poem? And I think it’s it’s all to do with that contrast between the repulsive, frightening, dull-witted shark and the zippy little pilot fish gliding around him.

So on the one hand, there’s the shark with ‘his saw-pit of mouth’ and ‘his charnel of maw’, his mouth of death, with ‘his ghastly flank’ and ‘his Gorgonian head’, and later on we get the ‘serrated teeth’ and the ‘jaws of the Fates’, and the shark ravening the ‘horrible meat’. Which creates a pretty sombre tone, does it not?

But it’s all described in this wonderfully jolly and zippy ballad form, swirling along like a waltz, with its jingling rhymes, as Milton would describe them:

From his saw-pit of mouth, from his charnel of maw

They have nothing of harm to dread,

But liquidly glide on his ghastly flank

Or before his Gorgonian head;

So Melville is really relishing the horror, and camping it up in Gothic fashion, but dancing nimbly around it, just as the pilot fish are gliding around the shark. The poem has the jauntiness and jollity of a nonsense rhyme. And if you think you’ve heard this kind of ballad music before, then perhaps you’re casting your mind back to Episode 6 where we looked at Edward Lear’s nonsense poem, ‘The Jumblies’, another ballad of the sea:

They went to sea in a Sieve, they did,

In a Sieve they went to sea:

In spite of all their friends could say,

On a winter’s morn, on a stormy day,

In a Sieve they went to sea!

And I chose this poem for the same reason I chose the Jumblies – I love the sound of it, the swing of it, the images it creates in my mind and sheer delight in the poet’s dexterity with words.

And it’s also, as I say, a wonderful treatment of symbiosis in nature, the mutually-beneficial relationship between the shark and the pilot fish, which it not only describes but also embodies and mimics, in the contrast between the dark subject matter and the jolly rhythms.

OK in lines 9 to 12, what is effectively the third stanza, Melville gets to the heart of the matter, or rather the jaws of the matter. The pilot fish, are not only gliding around the shark, they are getting up and close with its mouth:

Or lurk in the port of serrated teeth

In white triple tiers of glittering gates,

And there find a haven when peril’s abroad,

An asylum in jaws of the Fates!

So for most creatures, including humans, getting close enough to see the ‘white triple tiers’ of ‘serrated teeth’ means you’re in deep trouble; those ‘glittering gates’ are the gates of death. But for the pilot fish, they are a ‘port’, a ‘haven’, and ‘asylum in jaws of the Fates’.

This is a pretty compelling image, it’s hard not to be drawn in by it. On one level, Melville is transfixing us with the sheer horror of a close-up of the shark’s teeth. On another, he’s delighting in the natural paradox of these small vulnerable fish being completely at ease with, and even relishing the sanctuary of, the jaws. And he expresses this paradox in a metaphor, comparing the jaws to the Fates.

From the perspective of the fish, of course, it’s just a decorative metaphor; fish don’t have the capacity to contemplate their fate. But human beings do, and the more I re-read this poem, the more I get the sense that Melville is nudging us to identify with the fish and to contemplate our own fate in the light of the poem.

That was certainly the opinion of Robert Penn Warren, the 20th century American poet and critic, in his essay on ‘Melville the Poet’. He compared ‘The Maldive Shark’ to other poems by Melville and suggested that ‘As the pilot fish may find a haven in the serrated teeth of the shark, so man, if he learns the last wisdom, may find “an asylum in the jaws of the Fates.”’.

We don’t want to get too heavy-handed in interpreting the poem, I certainly don’t think this is the ‘point’ of the poem, that we need to get. I think it’s actually more powerful that Melville is focused so intently on the shark and the fish themselves, rather than making a more explicit link with the human condition. But I think on some level, we can relate to this, the sense that life is uncertain and dangerous and it’s ultimately fatal; certainly this would have been Melville’s experience as a sailor at sea in the 19th century. And yet, somehow we manage to eke out a living, and find some kind of sanctuary ‘in the jaws of the Fates’.

This is of course a common theme in poetry. A couple of centuries before Melville, Andrew Marvell suggested to his mistress that they should ‘tear our pleasures with rough strife / Through the iron gates of life’. And in the century after Melville, W. H. Auden wrote that the job of the poet was to ‘teach the free man how to praise’, ‘in the prison of his days’.

There is, as I’ve said, quite a lot of fun and exuberance in Melville’s depiction of the pilot fish, but he doesn’t get as far as praise. His fish are ‘tweaking the nose of terror’, as Blackadder puts it, rather than singing a hymn of joy. And this becomes very apparent in the last four lines of ‘The Maldive Shark’:

They are friends; and friendly they guide him to prey,

Yet never partake of the treat—

Eyes and brains to the dotard lethargic and dull,

Pale ravener of horrible meat.

So Melville is really spelling out the symbiotic nature of the relationship – the fish are ‘friends’ of the shark who ‘guide him to prey’, they are his ‘Eyes and brains’. Yet they ‘never partake of the treat’, and Melville stops short of describing the shark as ‘friendly’. He is a ‘dotard lethargic and dull, / Pale ravener of horrible meat.’

And what an absolutely brilliant and horrible and unforgettable last line that is. There is absolutely no music in that line, no alliteration, no assonance, no sonic beauty at all. It feels clumsy and clunky. The rhythm is like a cleaver being thunked through a hunk of meat on the butcher’s slab. The final word, ‘meat’ does rhyme with ‘treat’, but rather than chiming with it, it feels to me like it’s destroying any residual positive connotations of the word ‘treat’. What’s a ‘treat’ for the shark is repulsive for the reader, so Melville’s use of the word ‘treat’ feels pretty grimly ironic.

And what this ugly, brutal last line does is it lodges the image of the shark in the reader’s mind, like those terrifying photographs of a great white shark looming out of the darkness. And clearly, Melville is much better known as a novelist than a poet, and I don’t think anyone is going to claim he’s one of the greatest poets who ever lived, but this little poem is really remarkable, for the contrast between the quickness and pluckiness of the pilot fish and the brute reality of life and death and fate, as embodied in that final image of the shark closing in.

The Maldive Shark

By Herman Melville

About the Shark, phlegmatical one,

Pale sot of the Maldive sea,

The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim,

How alert in attendance be.

From his saw-pit of mouth, from his charnel of maw

They have nothing of harm to dread,

But liquidly glide on his ghastly flank

Or before his Gorgonian head;

Or lurk in the port of serrated teeth

In white triple tiers of glittering gates,

And there find a haven when peril’s abroad,

An asylum in jaws of the Fates!

They are friends; and friendly they guide him to prey,

Yet never partake of the treat—

Eyes and brains to the dotard lethargic and dull,

Pale ravener of horrible meat.

Herman Melville

Herman Melville was an American novelist and poet who was born in 1819 and died in 1891. As a young man he enlisted as a common sailor on merchant ships and whaling expeditions, which inspired his masterpiece, the novel Moby-Dick. Later in his career, Melville turned to poetry, and his poetical works include a book of ‘Battle Pieces’ about the American Civil War, and Clarel, an 18,000 line epic poem that grew out of his trip to the Holy Land in 1856. Although his books were not always well received during his lifetime, he is now regarded as one of America’s greatest writers.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith

Episode 70 Drinking Ode by Matthew Buckley Smith Matthew Buckley Smith reads ‘Drinking Ode’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: MidlifeAvailable from: Midlife is available from: The publisher: Measure Press Amazon: UK | US...

The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden

Episode 69 The Great Fire of London, from Annus Mirabilis by John DrydenMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage about the Great Fire of London from Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.Poet John DrydenReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Great Fire of London,...

0 Comments