Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Episode 48

The Windhover by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Mark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘The Windhover’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Poet

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

The Windhover

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

To Christ our Lord

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.

Podcast transcript

This poem would be mind blowing if it were published today. But believe it or not, it was written in 1877. It’s so far ahead of its time that it’s hard to imagine how strange it would have sounded to Hopkins’ contemporaries, deep in the heart of the Victorian era.

You know, for reference, round about the same time, Tennyson was finishing his epic poem about King Arthur and his knights, The Idylls of the King. And then Hopkins comes along with this poem that is radically experimental and modern, that anticipates some of the big technical innovations of 20th century poetry. But at the same time, it has deep roots that we can trace all the way back to Anglo-Saxon poetry, before the Middle Ages. So it’s a poem that combines old and new.

And it is a deeply and explicitly Christian poem, that is also, at the same time, extremely sensuous, even sensual. And there’s more than a hint of pagan imagery and the warrior ethos of that pre-Christian, Anglo-Saxon culture.

It focuses on the miracle of flight, of a small hawk, the windhover, which is an old name for the common kestrel, or Eurasian kestrel, which lives mostly in Europe and Africa and Asia. But here in the UK it’s the only kestrel we have, so these days we just call it a kestrel. But of course, the older name, windhover, is a much more evocative name than kestrel.

And it’s called the windhover because it does just that – it has this amazing ability to hover in the air, by flapping its wings really fast. And it looks at the ground, as it’s hovering, for some prey to snaffle. And then it swoops down when it sees a suitable target.

And I’ve been lucky enough to see kestrels quite a few times while out walking and it’s an amazing sight, it’s almost like a cross between a hawk and a hummingbird.

And this is the behaviour that Hopkins is describing in the poem. So it’s a poem of tension between this tiny creature and the big winds that threaten to dislodge it and sweep it away, but it’s maintaining its poise, and it’s holding its position. And it’s a glorious sight that for Hopkins is symbolic of the glory of Christ, he makes this clear in his dedication: ‘To Christ our Lord’.

By the way, this is another Anglo-Saxon link. I remember reading an old Anglo-Saxon text at college, arguing that the sight of a hawk in the sky was proof of the reality of the Christian revelation, because the hawk is shaped like a cross – and my tutor explained that this was ‘argument by analogy’, which has fallen out of fashion somewhat, since Anglo-Saxon times.

So there are a lot of tensions in the poem: they are embodied in the figure of this hawk riding the wind and in danger of being thrown off. And also, between the traditional and the experimental verse forms, and between the pagan and the Christian, the sensuous and the spiritual.

And we can trace these tensions in Hopkins’ personality. He was a Catholic priest in the strict Jesuit order. Apparently, this poem was written when he was in North Wales studying theology at St. Bueno’s college, so presumably he saw it while he was out walking, and as he says, ‘my heart in hiding / Stirred for a bird’. And the sight spoke to him of the Christian revelation, but he expresses it in such a vividly language that, whether we are Christians or not, it’s a very joyous and exhilarating and exciting poem to read.

Okay, so let’s just orient ourselves in what’s going on, because, it is a very disorienting poem, and I think deliberately so. I’ve read it hundreds of times, but you may well have just listened to this for the first time and thought ‘What on earth is going on here?’ The words and the images tumble out so fast, and that’s by design, Hopkins wants to knock you off your feet and sweep you along, like the hawk in the wind.

So he starts off:

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

So this morning he saw a hawk, a falcon, which he compares to the Dauphin. So back in the day, when the French had a monarchy, the Dauphin was the title given to the heir to the throne, it was the French equivalent of the Prince of Wales. And of course any mention of the Dauphin, if you are a Shakespeare fan, as Hopkins was, will take you to Henry V and the eve of the Battle of Agincourt. And I have no doubt Hopkins intended us to think of the Dauphin boasting about his horse in these words:

He bounds from the earth, as if his entrails were hairs, le cheval volant, the Pegasus, qui a les narines de feu. When I bestride him, I soar; I am a hawk; he trots the air.

So the Dauphin describes his horse as ‘le cheval volant’, the flying horse, the Pegasus, with ‘narines de feu’, nostrils of fire, and when he mounts the horse, he compares himself to a hawk, riding the air. And so Hopkins is returning the favour, comparing the hawk riding the air to the Dauphin.

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy!

So in these first four lines of the poem Hopkins hangs the hawk up for our contemplation, just as it hangs itself in the sky. And he does it in this incredibly rich language, ‘daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon’, you can hear the alliteration, those repeated ‘d’ sounds; and the combination of the sound patterns and the imagery creates a dappled effect that is very characteristic of Hopkins’ poetry.

So he hangs the hawk up there, just after the dedication to ‘Christ our Lord’, and compares it to the Dauphin. And in one of his letters, Hopkins says very clearly, that he intends the windhover to be ‘the symbol or analogue of Christ, Son of God, the supreme Chevalier’. And apparently this was a thing in medieval writing, to compare Jesus to a knight in shining armour. And it was probably natural to Hopkins, given that his order, the Jesuits, was founded by a soldier, Saint Ignatius of Loyola, and Jesuits were often referred to as ‘God’s soldiers’. It also explains why Hopkins wrote another poem about a soldier, a 19th century British redcoat, and compared him to Jesus.

Okay, back to the poem.

then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

So the windhover doesn’t just hover, he can glide as smoothly as an ice-skate. And ‘the hurl and gliding’ of the bird, ‘Rebuffed the big wind’. And that word ‘rebuffed’ suggests that, weirdly, the tiny bird is equal to the wind and its buffeting, the windhover can ‘rebuff’ it, resist it and drive it back. And I do think we’re intended to pick up the word ‘buffeting’, from the word ‘rebuffed’, suggesting the way the hawk is buffeted by the wind and somehow manages to rebuff it. So it’s a wonderfully compressed and suggestive expression.

And as he watches the bird riding the wind, Hopkind tells us:

My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

That’s a very telling phrase isn’t it? ‘My heart in hiding’ – it suggests that Hopkins sees himself as quite an introverted, withdrawn, timid person. He’s nowhere near as brave and bold as the hawk, let alone Jesus. But he says his heart stirs at the sight, ‘the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!’. He’s amazed at the incredible skill and mastery it takes to ride the wind.

Okay, so that’s the first eight lines. And that number should be a clue for us, shouldn’t it? If you’ve been listening to this podcast for a while, your poetic radar must be twitching and you’re probably wondering whether this is a sonnet. Because the basic structure of the Petrarchan sonnet, as Mimi Khalvati told us back in Episode 3, is eight lines, called the octave, where the poet sets the scene or gives us one point of view, followed by six lines, the sestet, which gives us another perspective on the subject.

And indeed this is a sonnet, so we should expect a turn at this point, as the poet shifts or pivots into another way of looking at the subject. Which is exactly what we get:

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

Again, you might be forgiven for asking, ‘What exactly is going on here?’ So let’s zoom in for a closer look. The ninth line is basically a summing up of everything he’s described in the octave: ‘Brute beauty’, ‘valour’, ‘act’, i.e. ‘action’, ‘air’, ‘pride’, and the ‘plume’, the feathers, of both the hawk and the knight in armour. So he lists these things and says that here they ‘Buckle!’. All of these things buckle.

So there’s an enormous amount of weight brought to bear on that word: buckle. But what does he mean by it? I mean to us, we probably think of the buckle on a shoe. But there are other meanings for that word. And scholars have been arguing about the meaning of this word in ‘The Windhover’, since it was published. And there are various meanings that have been put forward.

Firstly, our modern meaning, of ‘clasp or fasten together’, could well be relevant here. Which would mean Hopkins is saying that all of these things come together and are joined together, in the figure of the bird, who we should also remember is Christ.

Other, older meanings, are ‘to prepare for battle’, and ‘to engage with the enemy’. The word pops up in this sense several times in Shakespeare’s history plays, which we’ve already seen were in Hopkins’ mind as he wrote ‘The Windhover’. And a ‘buckler’ was a small shield used in hand-to-hand combat.

So the modern shoe buckle and the ‘buckling’ of warriors have quite different associations, but what they have in common is that they are about bringing things together, whether gently or violently.

But there is another meaning, that threatens to override both of these meanings, and that is ‘to break, to crumple, to bend or collapse’ under pressure. Which suggests that, brave and skilful though he is, the kestrel is asking for trouble by riding the wind. He could easily be broken by the ‘brute’ force of the wind.

Hopkins may also be thinking of another line from Shakespeare, in Much Ado about Nothing, when Benedick says to Margaret, ‘I give thee the bucklers’, meaning ‘I give in, I surrender’.

So which meaning of ‘buckle’ should we choose? Well, I don’t see why we shouldn’t go for all of them at once.

Right from the beginning of the poem, there is clearly some king of military metaphor going on, so it feels natural to pick up the military senses of the word ‘buckle’, and to see the hawk arming itself for battle, clashing with the wind like an opponent, and buckling under the blows it receives.

So he’s fighting the wind, but he’s also joining with it, buckling with it in that sense. And if we look at the scene the way a theologian or philosopher might look at it, we can see that even though the hawk and the wind appear to be antagonists, in conflict with each other, ultimately they are part of a larger pattern where the two sides are part of a larger whole.

And remember that the windhover is a symbol of Christ, and it’s a commonplace of Christian theology that the Crucifixion was a paradoxical moment, the moment of Jesus’ greatest suffering and humiliation when his body was broken, when it ‘buckled’, but it was also the a glorious moment, the moment of his greatest triumph.

And this is pretty well what Hopkins says next:

AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

So immediately after the word buckle we get ‘AND the fire that breaks from the then’. And I think this sentence has got to be deliberately ambiguous and suggestive. It’s hard to pin down exactly what he means by this ‘fire’, but I think we can feel it, can’t we? A fire ‘breaking’ from the hawk that is lovely and dangerous, and evidently holy and glorious.

And it’s possible that the change of pronouns, from ‘he’ and ‘his’ and ‘him’ in the octave describing the kestrel, to ‘thee’ here, means that Hopkins has turned from contemplating the bird to addressing Christ – the poem is addressed ‘To Christ our Lord’, after all.

My overall impression here is of language itself buckling under the weight of meaning, and the sheer energy of Hopkins’ verse, as he struggles to express something that is really ineffable. Which again, is entirely appropriate to his religious subject.

And just as we might be scratching our heads and wondering what he’s getting at, the poet steps in and tries to steady us with a couple of closing analogies:

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.

If you’re wondering what ‘sillion’ is, then so did I. A trip to the dictionary reveals that it’s an old-fashioned poetic word for a furrow of earth being turned over by a plough. So he’s saying that the plodding of the ploughman is what makes the freshly ploughed earth, or maybe the plough, shine.

And the second image makes a similar point – that it’s when the embers of a fire fall, that they ‘gash gold-vermilion’, they reveal the glowing heart of the fire within. So these two ‘arguments by analogy’ seem to be driving the point home, that glory is found unlikely places, often at the point of greatest danger or greatest endurance or even the moment of falling.

Okay, so that’s the gist of what’s going on in the poem, and in the poet’s mind, as far as I can decipher it. But it’s really the style of this poem that makes it such a startling and unforgettable experience.

So, as I said, the poem has the clear division between the octet and the sestet of the classic Petrarchan sonnet. And in one sense Hopkin keeps a very closely to the traditional form. He adheres very strictly, even absurdly strictly, to the traditional rhyme scheme, the rhyming pattern, which in the first eight lines goes ABBA ABBA. In other words, there are only two rhymes, you’ve got two couplets, the B rhymes, nestled inside each quatrain, and enclosing them, enveloping them, are the A rhymes that appear before and after each couplet.

And as I’ve said before on the podcast, it’s much easier to find rhymes in Italian than it is in English, so a lot of English poets fudge this bit, or vary it, so that they don’t have to find two sets of four rhymes. But Hopkins doesn’t fudge it. His A rhymes are ‘king’, ‘wing’, ‘swing’ and ‘thing’. And his B rhymes are ‘riding’, ‘striding’, ‘gliding’ and ‘hiding’. So not only does he use nice full rhymes for the A and B rhymes, but these two sets of rhymes even rhyme with each other!

They are different, because of the stress pattern: ‘king’, ‘wing’, ‘swing’ and ‘thing’ are masculine rhymes, meaning they end with a stressed syllable; and ‘riding’, ‘striding’, ‘gliding’ and ‘hiding’ are all feminine rhymes, meaning they end with an unstressed syllable. So Hopkins is basically showing off here, he’s taking a demanding rhyme scheme and making it even more difficult, by making all eight words rhyme together in a row. Which is kind of insane. Off the top of my head. I can’t think of anyone else who has done this, for obvious reasons.

And then in the sestet, the last six lines, he again goes for the most difficult of the various traditional rhyme schemes, allowing himself just two rhymes and rhyming ‘here’, ‘chevalier’, and ‘dear’, which are relatively ordinary rhymes. But then he ends with a flourish, rhyming ‘billion’, ‘sillion’ and ‘vermilion’, which is pretty ostentatious. Firstly, we have to get the dictionary out for ‘sillion’, next he’s rhyming three syllables in all three rhymes, and just for good measure, he ends with a four-syllable word, ‘vermilion’.

So these rhymes are calling attention to themselves. And I haven’t even touched on all the internal rhymes, rhymes buried in the middle of lines, that are scattered throughout the poem.

Which means Hopkins is pushing his rhyme about as far as you can, before it starts to sound ridiculous. And maybe for some people it does sound ridiculous. And I wouldn’t I wouldn’t protest too much if you said look, come on, this is too distracting, I can’t take it seriously.

So whether we like it or not Hopkins, sticks extremely strictly to the traditional rhyme pattern, but in another way, he is very free and easy in his use of the sonnet form and that way is the metre.

We have encountered quite a few times on this podcast have are written in a regular metre, based on set patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables. The most common metre we’ve seen for sonnets is the good old iambic pentameter, which goes tiTUM, tiTUM, tiTUM, tiTUM, tiTUM. And this was the default metre for sonnets in English up to the 19th century.

But Hopkins doesn’t use iambic pentameter, he uses something he calls ‘sprung rhythm’, where there is a set quantity of stresses per line, but the number of syllables can vary quite dramatically, in order to capture the natural and expressive rhythms of speech and also the expressive rhythms of emotionally charged speech.

Now, scholars have spent an awful lot of time and ink debating exactly what Hopkins meant by sprung rhythm and whether it works in the way he described it. But you will be pleased to know we don’t need to go down that rabbit hole today. The essential point is that he’s writing in a mode where the stress patterns are governed more by expressive rhythms of speech than by a regular metrical beat.

And in one sense, this is of course very modern, it clearly anticipates the free verse revolution of the 20th century. Which led to the situation we have today where most poets don’t write in a regular metre they they try to capture the rhythms of natural speech. And this is what Hopkins was doing all the way back in 1877. So in that sense, ‘The Windhover’, is a very modern poem.

But sprung rhythm also harks back to a very old metrical tradition in English and that is stress metre, where the number of stresses in the line are regular, but the number of syllables between them can vary. Hopkins himself said he wasn’t inventing sprung rhythm so much as rediscovering it, from folk songs and Shakespeare and other older poets. And we have encountered stress metre on the podcast before, in the anonymous ballad ‘The Unquiet Grave’, back in Episode 22, and also, although I didn’t talk about it in that episode, in the medieval song, I read last Christmas ‘I sing of a Maiden’, in Episode 42.

Another thing that links ‘The Windhover’ to this older poetic tradition, is Hopkins’s use of alliteration, which is the repetition of consonant sounds at the start of words. For example we can easily here the repeated ‘m’ sounds in the first line of the poem, and ‘d’ sounds in the second line:

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,

Alliteration is a governing sonic principle in a lot of medieval poetry, such as Gawain and the Green Knight or Piers Plowman, and we can trace it all the way back to Anglo-Saxon poetry, to the age of Beowulf.

Some poets use alliteration sparingly and subtly, but not Hopkins. If we includ the ‘dom’ of kingdom, then in the second line, Hopkins has given us one, two, three, four, five, six words in a row, beginning with ‘d’!

[king]dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,

And this sounds kind of mad, but maybe not so much when we compare it to the opening lines of William Langland’s Piers Plowman:

In a somer seson, whan softe was the sonne,

I shope me into shroudes as I a shepe were

Which roughly translates as:

In a summer season, when soft was the sun,

I dressed myself in clothes as if I were a sheep.

So you could say, as Hopkins did, that he was reviving an older poetic tradition, rather than prophetically anticipating the free verse of the 20th century. But one thing that separates Hopkins from this older alliterative tradition is that, poets generally choose to either have a lot of rhyme in their poem or a lot of alliteration. They generally don’t do both at once. But Hopkins does!

He has absolutely slathered the poem in alliteration, as well as assonance, which is basically rhyming on the vowel sounds rather than the consonants. And we have seen that he is also laying the rhyme on incredibly thick. So what Hopkins is doing is very idiosyncratic, to put it very midly. I mean, you have to be a genius to get away with it. Which fortunately he was.

Now personally, I have been foolhardy enough to translate Chaucer and to imitate poets like John Donne and William Blake and T. S. Eliot in my own poetry. But I would never dream of trying to imitate Hopkins because I know for a fact, I would fall flat on my face. And even Hopkins, you could say, doesn’t get away with it entirely. There are moments in this poem when I think he is taking it a bit too far. You know, ‘my heart / Stirred for a bird’, and rhyming ‘sillion’ and ‘vermilion’ are teetering on the edge of ridiculousness. And it would be quite easy to parody Hopkins, if we didn’t love him so much.

Anyway, the main point I’m making here is that Hopkins use of poetic form, especially his use of sprung rhythm, is a bit like his use of the word ‘buckle’ because you can read it or experience it in several different ways and maybe all of them at once. You could see sprung rhythm as anticipating 20th century free verse. You could see it harking back to the Anglo-Saxon roots of English poetry. Or you could see it as a collision or a joining of the two ways of writing – Hopkins is buckling them together, and maybe they are fighting each other and jangling rather than chiming together.

And Hopkins is not everyone’s cup of tea, but he is definitely one of my favourite poets, and this is one of my favourite poems, and it’s become so popular, and anthologised and repeated that it even makes an appearance in an episode of The Simpsons. Believe it or not, the Simpsons character does a pretty good reading of the poem. If I can find a legal version on YouTube I will link to it in the show notes for your enjoyment. [Here’s the link – the poem is at 3 minutes 20 seconds. Enjoy!]

And because this is one of my favourite poems, I’ve known from the start that I wanted to do it on the podcast. I must admit I’ve been working myself up to it because I’d say it’s probably the most challenging poem to read out of all of the poems that I have recorded so far. Even the Shakespeare speech, where I was yelling so loud that my wife, who was in the house at the time, got quite alarmed!

And what I would say from my experience of reading out loud, as well as in my head is that, to appreciate it, you really need to let go and go with it, to get caught up in the gusts, and the cross currents of Hopkins’s rhythms and sound patterns, just as the hawk is buffeted to and fro by the wind.

And Hopkins is pretty self-deprecating, he describes himself as the guy on the ground with his heart in hiding, but actually, he’s the one who wrote the poem. He’s the one who gave us this glorious explosion of ‘Brute beauty and valour’. And the poem affects me the way the hawk affected Hopkins – each time I read it, I’m left staring in wonder at ‘the achieve of, the mastery of the thing’.

The Windhover

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

To Christ our Lord

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

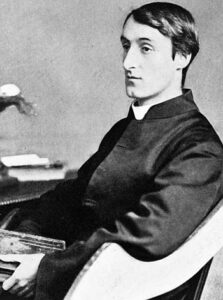

Gerard Manley Hopkins was a poet and Catholic priest who was born in 1844 and died in 1889. He converted to Catholicism at a time when anti-Catholic sentiment was still strong in England, and his conversion led to his estrangement from his family and several friends. He was a man of contradictions: he often felt a tension between his poetry and his religious vocation, so that he entered the Jesuit order he burned his poems and he only published a handful of them during his lifetime. He suffered periods of depression throughout his life, but his poems express moods of extreme joy as well as despair. On his deathbed his last words are recorded as ‘I am so happy, I am so happy. I loved my life.’ In 1918, thirty years after Hopkins’ death, his friend Robert Bridges published the first collected edition of his poems, and he is now regarded as one of the major poets of the 19th century.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

Empathy by A. E. Stallings

Episode 74 Empathy by A. E. Stallings A. E. Stallings reads ‘Empathy’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: This Afterlife: Selected PoemsAvailable from: This Afterlife: Selected Poems is available from: The publisher: Carcanet Amazon:...

From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer

Episode 73 From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, by Emilia LanyerMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer.Poet Emilia LanyerReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessFrom Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Lines 745-768) By Emilia...

Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani

Episode 72 Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani Z. R. Ghani reads ‘Reddest Red’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: In the Name of RedAvailable from: In the Name of Red is available from: The publisher: The Emma Press Amazon: UK | US...

0 Comments