Podcast: Play in new window | Download

‘you are not in search of’

by Martyn Crucefix

‘There has to be / A sort of killing’ – Tom Rawling

you are not in search of a gilded meadow

though here’s a place you might hope to find it

the locals point you to Silver Bay

to a curving shingled beach where once

I crouched as if breathless as if I’d followed

a trail of scuffs and disappointments

and the wind swept in as it usually does

and the lake water brimmed and I knew the thrill

of its mongrel plenitude as colours

of thousands of pebbles like bright cobblestones

slid uneasily beneath my feet—

imagine it’s here I want you to leave me

these millions of us aspiring to the condition

of ubiquitous dust on the fiery water

one moment—then dust in the water the next

then there’s barely a handful of dust

compounding with the brightness of water

then near-as-dammit gone—

you might say this aloud—by way of ritual—

there goes one who thought much of life

who found joy in return for a little gratitude

before its frugal bowls of iron and bronze

set out—then vanished—then however you try

to look me up—whatever device you click

or tap or swipe—I’m neither here nor there

though you might imagine one particle

in some stiff hybrid blade of grass

or some vigorous weed arched towards the sun

though here is as good a place as any

you look for me in vain—the bridges down—

Interview transcript

Mark: Martyn, where did this poem come from?

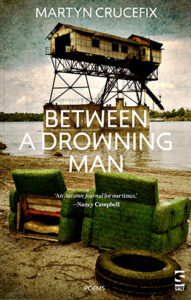

Martyn: It’s very interesting reflecting on where poems come from. Some poems have a very simple sort of origin. Rilke talks about a particular tree on a particular hillside, or an overheard conversation. Something of that sort. This poem has a more mixed background to it, I think, partly because it is a poem which occurs late. It’s the penultimate poem in an almost book-length sequence of poems in my new book, called Works and Days.

So looking back, I managed to find the notebook where the very first sort of scribblings for this poem occurred and maybe we can talk about that later. But it does go back a number of years to the winter, really, of 2015, 2016, and some of your listeners may remember that was a particularly stormy winter. I think it was Storm Desmond. I’m fascinated by the way in which we domesticate these terrible natural occurrences. Storm Desmond swept, particularly across the north of England, caused terrible property damage and flooding, and in particular in Cumbria in the Lake District, caused a great deal of damage.

And I was up there in the spring of 2016, and the kind of walks that I’d imagined us taking had to be completely rerouted or indeed completely abandoned because of these bridges being down. So communication was much disrupted and everybody’s plans and so on were affected by this.

So then idea of the bridges coming down, which does make an appearance in this particular poem, was a very literal observation. At the time I was experimenting with a new sort of writing for me, really, I’d picked up, as I often do, I think, in a second-hand bookshop, a really fascinating book, an old penguin classics book called, Speaking of Śiva. And this was translations by A. K. Ramanujan of, in effect, medieval Southern Indian lyric poems, which all addressed the God Shiva. These poems are generally called vacanna poems.

And I was interested in them because, despite their sort of antiquity, really, they were at least in the translations, wonderfully simple, the devices they used, repetition and refrain, and the range of emotion one might expect, kind of devotion and predictable emotions of that sort. But there was a great deal of anger and bafflement and confusion about God’s absence or what was being given to the poets.

And these vacanna poems always ended with a refrain which alluded to the god in a particular way. I don’t personally have a god, and it was a small step really for me to sort of realise that maybe the bridges being down might provide me with the kind of repeated conclusion, and that’s what happens in a lot of the poems in the book.

The other thing that was happening, of course, the great unmentionable in 2016 was the lead-up to the Brexit vote. And as I’m sure with many of us, I’d never experienced such a divisive period amongst friends and family, work colleagues I’d worked with for many years and I thought we had a lot of shared values. It turned out on this occasion we didn’t.

So that idea of communication breakdown, the bridges that one normally crosses personally, politically, and within a family were very, very powerful in my mind at the time. So a lot of that comes into, particularly say the early sections of the sequence. I think what is happening in this poem is an attempt perhaps at some sort of resolution or perhaps a moving on from that kind of conflict and division which I saw all around me.

Mark: Yeah. Yes. As we all did, sadly. The storm continued into the summer that year…

Martyn: Indeed, yes. And we seem to be still living with consequences.

Mark: That’s still rumbling on, yes.

Martyn: We should keep off that!

Mark: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, but it’s not just the UK, I know there’s a lot of people listening in different parts of the world, and I think, sadly, it’s a bit of a pattern in other parts of the world too.

Martyn: Absolutely. I think that the way in which, well, I suppose particularly in the West, divisions have arisen which seem irresolvable by conventional roots. The kind of dialogue that once took place seems not to be happening so clearly.

Mark: Right. And so I’m curious, how do you approach this as a poet? Because, I’ve got the benefit of having read earlier in the sequence. You certainly don’t approach it as the hectoring arguing citizen, you’ve come up with a very different kind of dialogue, a different perspective on this. But I mean, I’m curious. How did you…? Maybe the citizen, with your perspective, your investment on maybe one side of the debate, what’s the relationship between that part of you and then the poet who’s coming to speak about this?

Martyn: I think the poet in the sequence and indeed here is observing what is going on around, perhaps not making quick judgements, but I think this is the way in which a kind of literary precursor if you like, like these vacanna poems can help you. So I wasn’t aware that I was making especially political statements, I think, although in retrospect, I think I am. What I was doing at the time in a way which a lot of your poetry writing readers will probably recognise, I was experimenting and trying out a new way of writing.

So, these poems are very short. They make an observation. They make great use of repetition. I’m just looking at the notebook where the original sketches were made, and on the page opposite, I’m making use of one of these devices. So just to read four or five lines from this. I’ve got on the top of the page here.

‘Between rod and line, lip and kiss,’

‘Between brother and brother,’

‘Between mother and child,’

‘Town and country,’

‘Between money and wealth,’

‘Between north and south…’

And it goes on. So that refrain, that anaphora, simple repetition, really, of the between is something that I think I found in one of the vacanna poems, and I was simply trying that out. But what’s interesting in what I’ve just read is the north and the south divide, of course, and family divisions and so on, but also brother and brother.

And the other… you ask, how does one write about these things? The other precursor, if you like, lies behind the sequence, and that sustains you as a writer in developing what is a longer sequence. It’s very hard to maintain belief in what you are doing, but to have a model like the vacanna poems is very helpful.

And this other model which, again, I think I just happened to be reading at the time, was an ancient poem from the Western tradition, Hesiod’s Works and Days and A. E. Stallings, who I think has just been elected to professor of poetry at Oxford University in the last few months, she’s come to prominence through that, I think, but she’s a very good poet and a great translator. And she translated Works and Days. And Works and Days, in the introduction, she explains a lot of this, is actually based on a brotherly dispute. Hesiod is in dialogue, dispute, conflict with his brother who he gives the name Perses and Stallings observes that that’s a rather peculiar name. It perhaps means just something like ‘waster’ or ‘wastrel’ or ‘waste of space’.

Mark: A term of endearment for your nearest and dearest! [Laughter]

Martyn: Exactly. So, in that little bit that I read there from the notebook, conflict between brother and brother was also sort of in my mind as many of these poems developed.

Mark: Okay. So, can we zoom in maybe a little more closely on this particular poem? Say something about where this one came from. You say it was later in the sequence.

Martyn: The original scribble for this poem, there were two moments which I have coalesced in the process of writing it. And the beginnings, I’ll just read a little bit of this out. Top of the page, apropos of absolutely nothing particularly except what was in my head at the time, I guess.

‘Let’s imagine it’s late March, maybe April. Sunshine and showers coming north, from the real lakes, over the manmade one. Pine grove on Ren crag.’

So the landscape is very specific. Interestingly, that landscape is around Thirlmere, which many of you will know is one of the manmade lakes in the Lake District. The later poem is set very much in a specific place on Ullswater, which is one of the natural lakes on the eastern shore of Ullswater at Silver Bay, which is actually a specific place there.

A bit later on in the notebook, I seem to be revisiting the idea of sort of standing on the shoreline, but this is actually couched in the past tense:

‘I once crouched for minutes on this beach. This is Silver Bay.’

And that takes me to the ultimate kind of location of the final poem. In both cases, I’d seemed to have in my mind the idea of a scattering of ashes, and that seems to me now to be a kind of killing of the self, of myself, really. I think this could be read, and one or two lines from the poem are clearly couched in the idea of kind of advice to my children as to where I might indeed find myself scattered in the future. But this is a literal scattering of ashes, but obviously a metaphorical one.

And that does explain the epigraph, the little quotation at the top of the poem from Tom Rawling. Very few of the other poems in the sequence have epigraphs. They all stand alone. Most of them don’t really have titles. The title is the opening phrase of each poem. So this one is a bit unusual in having an epigraph.

Tom Rawling was an old mentor of mine from a long while ago. Back in Oxford, I was a postgraduate at the time, Tom was running a workshop, not a university workshop but a public arts centre workshop at the Old Fire Station in Oxford. And Tom had actually taken over from the great poet, Anne Stevenson, who was brought up in America, came over to the UK, lived a long time in Wales, I think. But Anne had been, for a year or two, in Oxford and had set up this workshop and had then moved back to Newcastle, I think.

Tom took it over, and he was an ex-headmaster, and he ruled us with a rod of iron in the workshop! And he hadn’t started writing until he’d retired from teaching at the age of 60. His background, he grew up on a very conservative, narrow-minded, he would himself have said, farm in Ennerdale in Cumbria in the Lake District. So there are lots of Lake District connections coming out here. This quote is from a poem called ‘A Sort of Killing.’ And Tom, way back in the late seventies, early eighties, quotes as an epigraph for his own poem something from Isaiah Berlin, which allowing for some of the kind of gender presumptions of the time, reads, ‘Society moves by some degree of parasite children on the whole kill, if not their fathers at least the beliefs of their fathers, and arrive at new beliefs.’

So the idea of death and the killing of fathers, and in my poem, I think the killing of previous selves, if you like, is more to do with a moving on of values. And the values earlier in the poem, as we’ve discussed, really, are very much the ones of division and sort of egocentricity, self-centeredness, greed, as opposed to one of the key words for me always, but also in this poem, of course, to imagine, that kind of moral imagination of escaping, if that’s the right word, from the confines of the self to understand, to empathise, to reach out to others. So that, I think, is partly why this poem imagines the scattering of ashes.

Mark: Right. So this is fascinating to me, Martyn, because I’m kind of laying this over my first reading of the poem, because you kindly sent me the proof of the book and you said you were thinking of reading this poem. So I read this one first, and then I went back and read the sequence. But one of the things I noted down on that kind of naive reading before I’d read any more of the sequence was I really homed in on the pronouns. And so the word ‘imagine’ appears twice. And, you say in the original note, it began, ‘Let’s imagine,’ but in the finished poem, that has separated out into ‘you’ and ‘I’, hasn’t it?

Martyn: Yes.

Mark: ‘You are not in search of a gilded meadow’. Straight away, that conjures up the question, ‘Well, who is you and who am I in relation to you?’

Martyn: Yes. Yes.

Mark: And then there’s a lot of provisional, hypothetical kind of subjunctive language in this: ‘You might hope to find it’, ‘Imagine it’s here’, ‘You might say this aloud’, ‘however’, ‘whatever device’, ‘I’m neither here nor there’, ‘You might imagine’, again, before, of course, we get to the bridges being down.

So there’s a real sense I picked up, even at first kind of naive reading without all that context, of this is two people exploring a hypothetical space or maybe one person hypothetically exploring it with somebody else. It really kind of lifts the whole poem into this realm of, it’s a bit like in the Lake District, when you walk up into the clouds, I guess, into the realm of possibility and hope, but maybe there’s some anxiety there as well.

Martyn: Absolutely. That’s really interesting. Yes. Yes. I think so. I mean, the ‘you’ from the opening line is probably that second person that poets often use when they’re referring really to themselves. But I think as I’ve suggested, this becomes… and I was sort of conscious as I was sort of drafting it, it was indeed becoming an address perhaps to my children about future wishes. And there’s another poem fairly close to this one which actually does address my children more directly. So there’s definitely that.

But I really like what you’re saying about the kind of provisional nature of this. This is absolutely an act of imagination and of hope that the kind of division and conflict which is so repeatedly kind of explored and discussed in the earlier poems, and as we’ve said, that refrain, ‘the bridges are down’, ‘the bridges are down’, ‘all the bridges are down’, is what keeps coming back.

Here, this is hope. It’s interesting you mentioned hope. In Hesiod’s poem, there is the first appearance of the Pandora’s jar myth, which, Pandora’s jar was a gift from the gods to humankind, but the lid of the jar was taken off and everything was lost. So we have to live… it’s a bit like the fallen world in the Christian tradition. We have to live with what we’ve got.

But the one thing that lodged in the neck of the jar was hope, and that is very much what is driving this poem. The kind of provisionality that you are responding to there for me is also contained within the pebbles, the cobblestones sliding uneasily beneath my feet. We have to accept, and I think this is an argument against the kind of rigidity of self and egotistic insistence that perhaps there is a simple solution to things. Away in the background here is Brexit and so on. There is no simple solution.

We have to work and improvise and continue to hope, and we have to walk into the lake upon these slippery cobblestones. But the cobblestones are coloured as the poem suggests, a plenitude. There is a richness, there is a set of possibilities, but not just one. And so that kind of subjective and provisional quality that you are talking about there I think is absolutely right. Yes.

Mark: And I guess I want to pick up as well on, some gorgeous phrases in here like ‘mongrel plenitude’, and that whole phrase, ‘The lake water brimmed and I knew the thrill of its mongrel plenitude.’ Later on, you’ve got ‘The condition of ubiquitous dust on the fiery water,’ and later ‘The handful of dust’ – with a nod to Eliot – ‘compounding with the brightness of water,’ and so on.

A lot of your poems have a lot of very everyday details like till receipts and Skype calls and so on, but you don’t do that in this poem. It’s much more gorgeous and elevated and maybe what we might think of as traditionally poetic diction. Was that a conscious choice, or did the poem just find its way there?

Martyn: I think it’s partly in response to what is earlier in the poem, as I said before, observations of telephone calls, traffic jams, noisy restaurants, cappuccinos in cafes and so on. So that kind of material is very much there. Here, yeah, I think you’re right. There is a more elevated sort of diction, I think. I think that’s partly I felt I was able to give myself permission for that, particularly in the idea of this being almost a ritual.

You know, when we scatter ashes, when we attend funerals and so on, there is a ritual quality to the language, and I felt that was possible here. Quite risky, as you say. That’s not especially what I do, and I think here that would be possible.

The other thing to say is, of course, there’s a phrase like ‘Near as dammit gone. The beauty and richness, the plenitude, the mixed.’ I mean, you mentioned ‘mongrel’. One or two people have queried whether I should be using a word like that in this day and age, but I’m partly using it about myself. My own background is very mixed in various ways.

Later in the poem, I think I’m imagining myself as that ‘hybrid blade of grass’. So any hint of a kind of purity of vision, I’m arguing against, I think. My vision is hybrid, mongrel, mixed, but the point being that makes it even more rich. And I think a way in the background here is, again, Brexit discussions, continuing discussions about the nature of UK society, multiculturalism, and so on, is not an irrelevant observation here, I think. Though I think a reader would not immediately think of those things.

Mark: Yeah. It’s lightly touched in.

Martyn: Yeah. Yeah.

Mark: And how did the form of this evolve? How close is this to what you had in that original note?

Martyn: My approach to form, I tend… Poets differ hugely on this, I think. My approach, I would describe as organic. My early notes tend to be, I’ve used the word scribbled several times, definitely scribbled, usually at high speed so that I don’t lose the moment or the feeling or the slant of light or something that’s in my mind. They come out in something of a jumble, and only later do I really begin to explore, I suppose, the possibilities of form.

I think this one moved into these three-line stanzas, these triplets, if you like, fairly swiftly. And I think I wanted this to be a fairly stately, ritualistic kind of movement through the poem as if a kind of an approach to a funeral or a scattering or something of that sort.

The indentations, a lot of the poems make use of indentation. And again, I definitely wanted to disrupt the reader’s experience, really, and to keep their eye moving swiftly from one thing to another. But again, compared to a lot of the poems in the sequence and in the book, really, this has quite a regular, formal shape to it, and that slow kind of procession is what I was hoping to achieve here, and I think it works okay.

The issue with form, of course, is that as soon as you start to begin to understand what form a poem should take, you then switch to beginning to impose a form upon the poem, and that has all sorts of consequences in terms of making you look more closely at whether a particular line is doing the work that it should be doing, whether it should not be there at all. The risk with form, and one finds this in poetry workshops a great deal, of course, is people filling out the form with unnecessaries.

Mark: Yeah. ‘You’ve got to fill it in here over here a bit, and then it will be done.’ [Laughter]

Martyn: Exactly, yeah. But hopefully, that’s not the case here.

Mark: No, no, absolutely not here.

Martyn: The other thing that is typical of my work sort of at the moment, really, is almost complete absence of punctuation. Just a few long dashes to give sort of hesitation and pause, and so on. And again, I’ve been working on that.

I remember reading the great American poet who died in the last couple of years, W.S. Merwin, and around the late 1960s I think it was, he abandoned punctuation completely. And it was something I’d been trying to experiment with. This was probably perhaps 10 years ago now, but he sort of gave me permission to really try. And again, it’s to do with what I’ve already mentioned, really. I want a kind of fluidity of vision, a rather bland word, but I think that’s the word I would use, rather than a compartmentalised, restrictive flow to the poem. So I’m trying to use the black of the print against the white of the page to suggest how the poem may be read. But that fluidity, again, is what I’m after.

Mark: Yeah, there is a nice combination of that regularity as you say, but also the fluidity. So if you’re listening to this, do go and have a look on the website, amouthfulofair.fm, and you’ll see you’ve got three-line stanzas, each one indented quite strongly. So it’s like three steps leading down. But that absence of punctuation and capitalisation and full stops, you’ve also got quite a lot of very skilful use of line breaks. It really feels like you’re stepping lightly from line to line and stanza to stanza.

Martyn: I hope that would be the feeling, and I think I’m stepping down into the chilly cold waters of Ullswater at Silver Bay, balancing tentatively in an improvisational way on those little rocks and pebbles and cobblestones, and I hope the poem feels a little bit like that. Yeah.

Mark: Yeah, it does. So maybe this would be a nice point for us to go down by the side of Silver Bay and join you there and listen to the poem again. So thank you very much, Martyn.

Martyn: Thank you, Mark. Pleasure.

‘you are not in search of’

by Martyn Crucefix

‘There has to be / A sort of killing’ – Tom Rawling

you are not in search of a gilded meadow

though here’s a place you might hope to find it

the locals point you to Silver Bay

to a curving shingled beach where once

I crouched as if breathless as if I’d followed

a trail of scuffs and disappointments

and the wind swept in as it usually does

and the lake water brimmed and I knew the thrill

of its mongrel plenitude as colours

of thousands of pebbles like bright cobblestones

slid uneasily beneath my feet—

imagine it’s here I want you to leave me

these millions of us aspiring to the condition

of ubiquitous dust on the fiery water

one moment—then dust in the water the next

then there’s barely a handful of dust

compounding with the brightness of water

then near-as-dammit gone—

you might say this aloud—by way of ritual—

there goes one who thought much of life

who found joy in return for a little gratitude

before its frugal bowls of iron and bronze

set out—then vanished—then however you try

to look me up—whatever device you click

or tap or swipe—I’m neither here nor there

though you might imagine one particle

in some stiff hybrid blade of grass

or some vigorous weed arched towards the sun

though here is as good a place as any

you look for me in vain—the bridges down—

Martyn Crucefix

Martyn Crucefix is a poet, critic and translator. Cargo of Limbs, his longer poem on the plight of refugees crossing the Mediterranean appeared with Hercules Editions in 2019, accompanied by photographs by Amel Alzakout. These Numbered Days, translations of poems from the German of Peter Huchel (published by Shearsman Books) won the 2020 Schlegel-Tieck Translation Prize. Martyn’s selected translations from across Rilke’s career is due from Pushkin Press in 2024 under the title, Change Your Life. Martyn is a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at The British Library and blogs regularly at MartynCrucefix.com

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer

Episode 73 From Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, by Emilia LanyerMark McGuinness reads and discusses a passage from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum by Emilia Lanyer.Poet Emilia LanyerReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessFrom Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Lines 745-768) By Emilia...

Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani

Episode 72 Reddest Red by Z. R. Ghani Z. R. Ghani reads ‘Reddest Red’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: In the Name of RedAvailable from: In the Name of Red is available from: The publisher: The Emma Press Amazon: UK | US...

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Episode 71 Ode on a Grecian Urn by John KeatsMark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ by John Keats.Poet John KeatsReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessOde on a Grecian Urn By John Keats I Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou...

0 Comments